A summer tour around lanes and villages in Sussex today paints a picture of abundance, affluence and idyllic English country life.

An agricultural or farm labourer living in the same lanes and villages just over 200 years ago would have had a very different perception of his environment.

The Battle of Waterloo had brought an end to the Napoleonic Wars in June 1815. Troops were demobilised and an economic slump followed. The Corn Laws were introduced as a protectionist measure that restricted grain imports, benefiting landowners and producers, but bringing about higher prices for staple foods such as cereal grains and bread. Agriculture was additionally impacted by expanding mechanisation and the enclosure of common lands. Unemployment climbed, prices rose and wages fell. In short, an agricultural worker found he had less money to pay more for essentials at a time when fewer labourers were needed.

Worsening the situation much further, a mountain over 7,000 miles away blew apart in April 1815. The volcanic eruption of Mount Tambora, the most powerful in recorded history, immediately killed 10,000 people on the island of Sumbawa. Dust spewed out into the atmosphere sparking a global catastrophe as dark cloud blocked sunlight for many months. Temperatures plunged and 1816 became “the year without a summer”. Days were cold, wet and dark with frequent storms so that harvests failed leading to further food scarcity.

This was a period that was, at the very least, gloomy, depressive and bleak and, at worst, seemingly apocalyptic.

I had a dream, which was not all a dream:

The bright sun was extinguished, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless and pathless, and the icy Earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air!

Morn came, and went, and came – and brought no day.

And men forgot their passions in the dread

Of this their desolation; and all hearts

Were chilled into a selfish prayer for light.

From Darkness – Byron, July 1816.

These were the years in which the Shipley Gang became the “terror of the county”.

The Shipley Gang

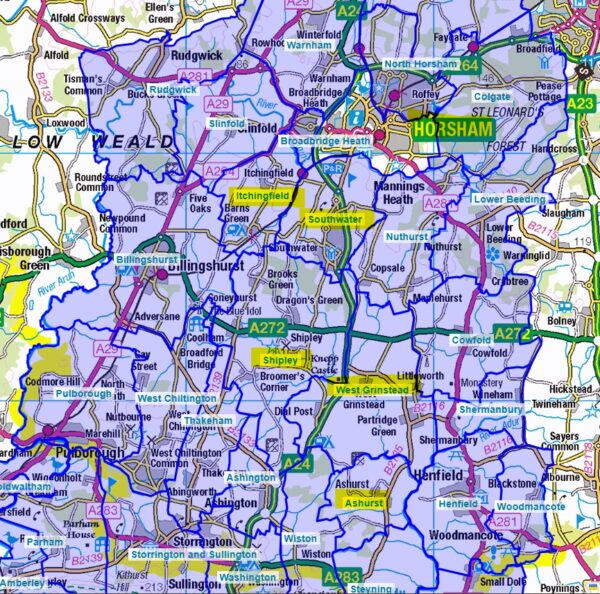

The Shipley Gang consisted of 12-15 thieves and housebreakers, mostly from or connected to the same local families – Nye, Rapley and Jupp. Their modus operandi was to work in different combinations. Arming themselves, they rode around the countryside targeting farms, mills and businesses. They surrounded a property, donned face masks and sometimes held the occupants as they carried out a robbery.

A number of accounts portray the gang as Robin Hood figures robbing the wealthy to feed the poor. Claire Wickens (The Terror of the County: A History of the Shipley Gang, 2001) concluded that the gang members were not of great social standing and may indeed have acted out of economic necessity to some extent. However, the organisation and nature of the crimes point to being motivated, at least partially, by financial gain.

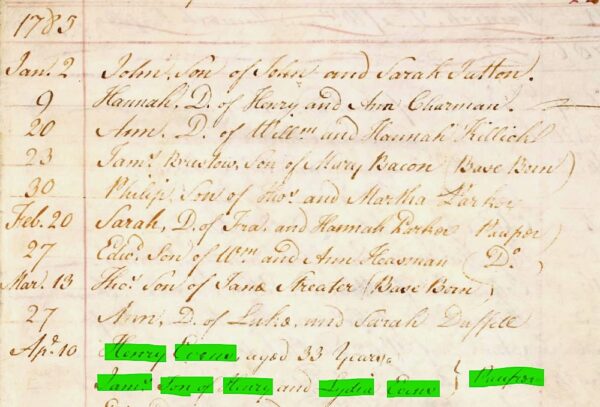

James Ewens was part of the Shipley Gang. His baptismal record at Shipley in 1785 noted that his parents, Henry Ewens and Lydia Boniface, my 5x great grandparents, were in fact paupers. He had seven siblings and his sister, Hannah, was my 4x great grandmother.

A labourer, James married Hannah Nye in 1810 and the couple had three children. Hannah’s brother and father, both named James Nye, were also gang members.

The gang was led by James Rapley, born in Shipley in 1767. James inherited both money and property but nevertheless had a history of theft and larceny. His children, Daniel, James and Sarah were involved in the Shipley Gang.

The Jupp family hailed from Horsham and gang members included Phillip Jupp, his wife Sarah (Knight) and their two sons, Henry and James. The banns on the intended marriage of James Rupp to Sarah Rapley were read three times in May 1817 but the couple never married.

The final members of the gang were William Brown, Henry Mitchell and Thomas Tilley.

Arrest

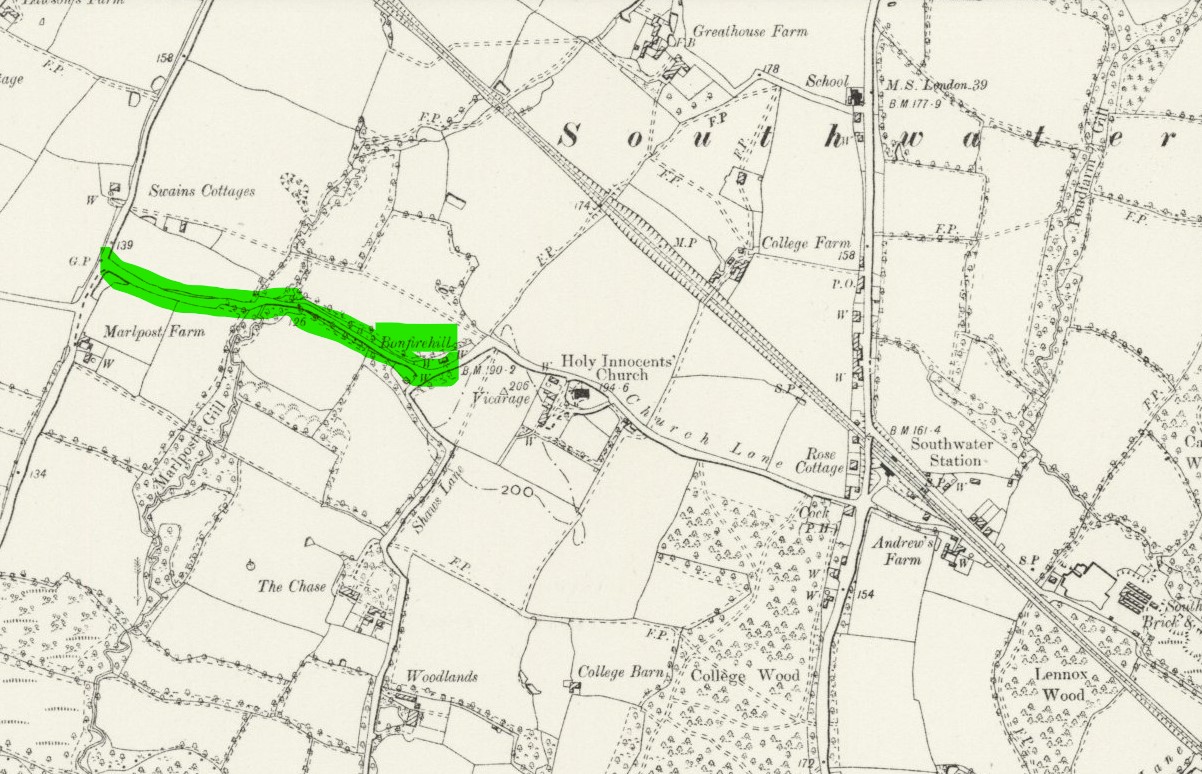

A number of sources state the gang had their headquarters in Southwater woods. An attempt to capture the robbers was made when the authorities learnt the gang intended to meet at a cottage at the bottom of Bonfire Hill in Southwater. A police constable guarded the front door while others burst into the cottage from the back. The lights were extinguished and a confused fight broke out in which several people were hurt. All the gang members managed to escape on this occasion.

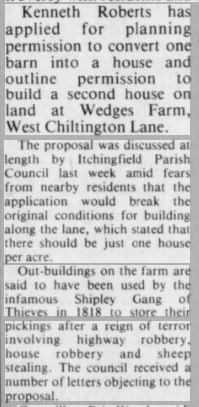

Nevertheless, local magistrates and constables were determined to apprehend the thieves that had “infested” the parishes of Horsham, Shipley and West Grinstead. James Ewens, James Nye(snr), James Nye (jnr), James Rapley, Philip Jupp and Henry Jupp were eventually arrested at Wedges Farm in Itchingfield in August 1817.

By August 17, a total of eight gang members were in custody in Horsham Gaol. The Rapley siblings, Daniel, James and Sarah and her intended husband, James Jupp, escaped but Daniel Rapley and James Jupp were in custody by December. James Rapley was not apprehended.

James Rapley (snr), the reported ringleader, was not held with other gang members at Horsham Gaol but transferred to the Petworth House of Correction. He hanged himself using a handkerchief fastened to the bars on the window of his cell on 24 August. A jury at the inquest into his death returned a verdict of insanity and he was buried at Petworth three days later.

Trial

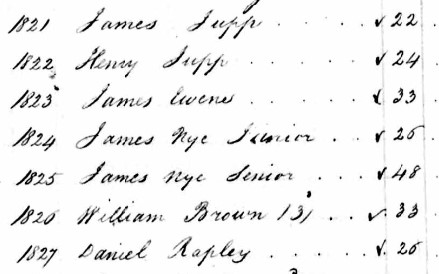

Remaining members of the Shipley Gang were put on trial at Horsham on 16 March 1818, charged with 18 counts of burglary, theft and sheep stealing. They pleaded guilty.

Thomas Tilley, Henry Mitchell and Sarah Rapley (as Sarah Jupp) were admitted as witnesses for the Crown and “discharged by proclamation”.

Sarah (Knight) Jupp appeared at court charged with larceny of a person but was not prosecuted. Her husband, Phillip Jupp, was indicted on three counts of theft for a fork, barrel and axe and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment with hard labour at the Petworth House of Correction. Phillip and Sarah continued to live in Horsham where Phillip died at the age of 73 and Sarah 75. Phillip did not give up on a life of petty crime though and spent further time in jail.

James Nye (snr) was charged with receiving stolen goods and sentenced to 14 years’ transportation.

James Ewens

James Nye (jnr)

Daniel Rapley

Henry Jupp

James Jupp

William Brown

were all sentenced to death, a sentence that was commuted to transportation for life “before the judges had left the town”.

Transport to the Colony

The seven members of the Shipley Gang sentenced to transportation made the same journey to New South Wales.

The first section of their voyage was transport from Horsham Gaol to Portsmouth where they were transferred to the Laurel prison hulk on 8 May. Hulks were decommissioned warships converted into floating prisons. Conditions were harsh and unhealthy since prisoners were kept in cramped and poorly ventilated spaces and fed a poor diet.

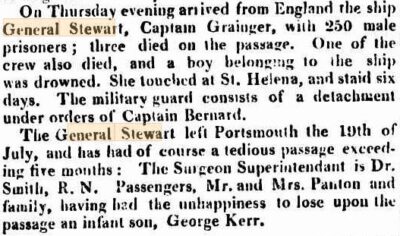

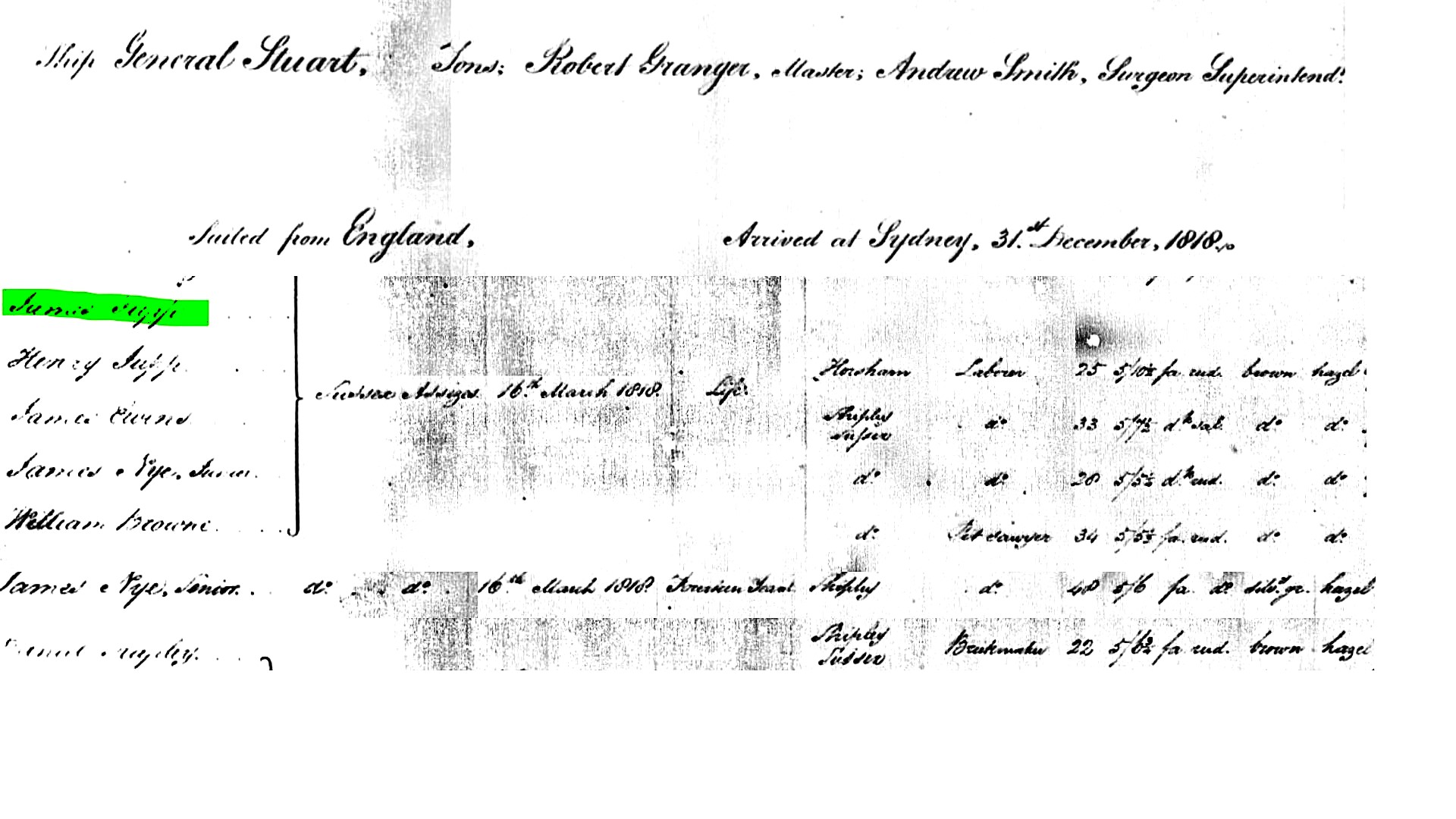

The convicts were boarded on the General Stewart (also General Stuart in documents) and sailed from England on 19 July. When the ship eventually arrived in Sydney on 31 December, the Sydney Gazette described the General Stewart as having had a tedious passage.

Dr Andrew Smith, the superintendent surgeon on board, made a report to Governor Lachlan Macquarie on arrival in Sydney in which he made complaints about the master and owner of the General Stewart, Robert Granger. Grievances included giving prisoners short rations, providing inferior food and treating prisoners harshly. The captain and soldiers guarding the prisoners also made depositions to complain about the quality of rum and mouldy bread they received. A Court of Enquiry did not uphold the case. This was the first convict transport made by the General Stewart though and it was never commissioned again.

James Jupp was probably one of the three convicts who died during this sea voyage. He cannot be traced after arrival in Australia and the convict list made on arrival does not give details of his crime or a physical description.

James Ewens

James Ewens, James Nye (jnr) and Henry Jupp were assigned to a road gang in Parramatta to the west of Sydney.

James Ewens was still in Parramatta in 1828 working in 19 road gang. In 1831, he appeared on the government labour exemption register in the district of Airds, Campbelltown.

A Ticket of Leave was a document issued to convicts granting them certain freedoms and allowing them to work for themselves or others and lease land within a specific area. It was a form of conditional release awarded for good conduct that represented a step towards eventual freedom or pardon. In November 1831, James was given a Ticket of Leave that permitted him to remain in the district of Airds.

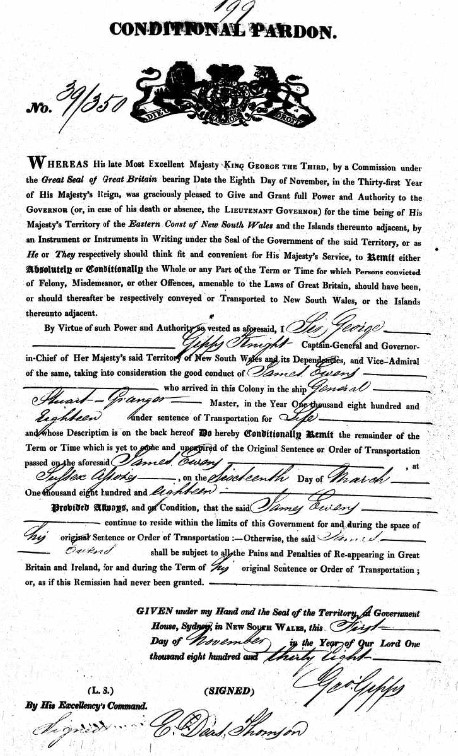

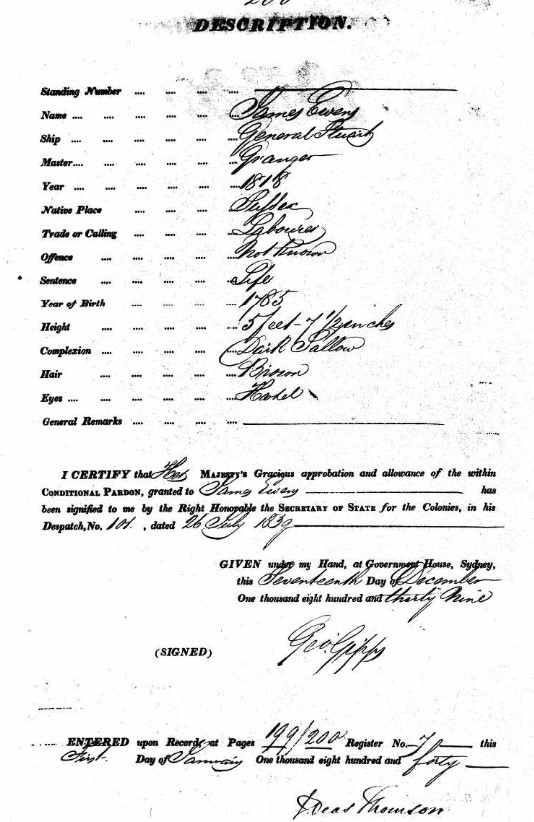

A Conditional Pardon granted freedom to a convict who had shown good behaviour. This meant the convict was freed from his or her original sentence, often a life sentence, and could live and work as a free person remaining bound to the colony unable to return to his or her homeland. James Ewens was granted a Conditional Pardon in November 1838.

James remained in the same district. He died on 6 June 1861 when he was 76 years old and was buried at St Peter’s Anglican Church in Campbelltown.

Hannah (Nye) Ewens

At the time her husband was arrested, imprisoned and later transported, Hannah lost her father and only sibling at the same time. She was 26 years old, left alone with three young children, John (7), Lucy (4) and Thomas (2).

She gave birth to an illegitimate child, Sarah Thompson Ewens, on 8 August 1824. The baptismal register recorded that Hannah was a widow. Sarah Thompson died in 1826.

All three of Hannah’s remaining children died at Shipley Workhouse in quick succession. John died when he was 19 on 10 April 1831 due to “decline”. Thomas’ death was also as a result of “decline” when he died on 27 July 1832 at the age of 16. Lucy married Thomas Anscomb when she was 17 and succumbed to consumption on 9 April 1834 just under four years later.

During this period, Hannah married Henry Francis, an agricultural labourer, in 1832. Henry’s mother was Ann Rapley, cousin to James Rapley, the leader of the Shipley Gang. The couple had one son, Henry Francis, in 1833 who died a few months later. His father died in 1860 and Hannah in 1865.

James Nye (snr)

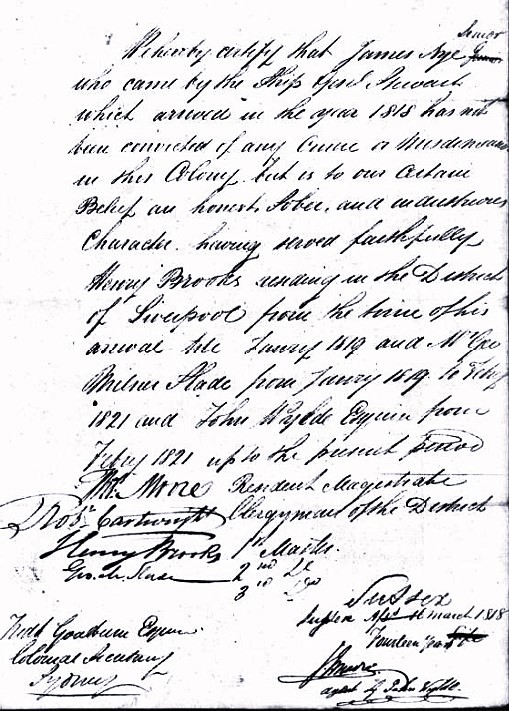

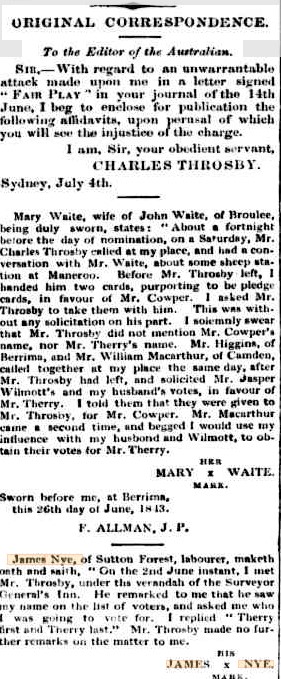

Hannah’s father was transferred to the district of Liverpool, to the north of Campbelltown and west of Sydney, and assigned as a government servant to the Henry Brooks family from April 1818 to May 1823. This letter of certification attested to his good character.

From 1823 to 1824, he was assigned to Mr Throsby, presumably Charles Throsby who had been granted land by Governor Macquarie at Throsby Park in Liverpool.

He was granted a Ticket of Leave that allowed him to stay in the district of Liverpool in 1825.

A year later he was given permission to marry Catherine Kelly, a convict transported from Dublin on the Mariner in 1825. Catherine came from Rathfarnham, to the south of Dublin, and had been sentenced to 7 years’ transportation for stealing clothes. She was noted as being “tolerable” on arrival in Sydney. A kitchen maid, she was 5ft 1½ins tall with brown hair and grey eyes. The Mariner only carried female convicts who were all sent to the Parramatta Female Factory. James Ewens was a witness at the marriage.

James Nye never saw out his full sentence of transportation of 14 years. Aged 60, he drowned on 1 October 1827 and was also buried at St Peter’s Anglican Church in Campbelltown.

James Nye (jnr)

James (jnr) had married Ann Stone and had a son, William, and a daughter, Emily, in England.

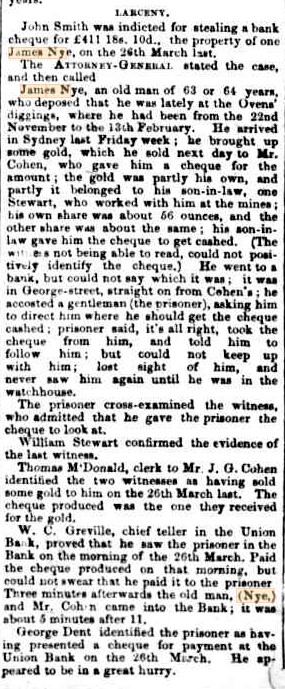

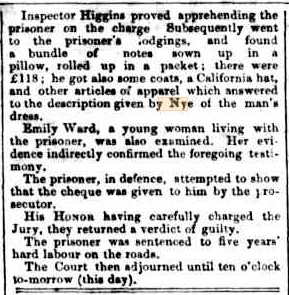

After working on a road gang, he was assigned as a labourer in the district of Liverpool. By 1828, he had a Ticket of Leave and he made an application to marry at Narellan, to the west of Campbelltown. His intended wife was Ann Mcdonnell from County Meath in Ireland. Ann had arrived in New South Wales a few months earlier on the ship Elizabeth, convicted of theft and larceny and sentenced to 7 years’ transportation.

The marriage was not allowed as it was claimed Ann McDonnell was already married and had a child. At this time, James was assigned to Charles Throsby and Ann to Charles Wright in Bong Bong near Sutton Forest. Both James and Ann were noted as having a good character. Later that year, James was in Sutton Forest, employed as a fencer by Charles Throsby.

In 1833, James and Ann were finally granted permission to marry at Bong Bong after making three further applications. By this time, Ann had a Ticket of Leave and was pregnant with the couple’s third child. The couple went on to have six more children.

Ann was granted a Certificate of Freedom in 1834 and James was conditionally pardoned in 1836.

James’ daughter in England, Emily, had married William Dorrington and they and their five children joined an assisted immigration scheme in 1854 to settle in Uralla in northern New South Wales.

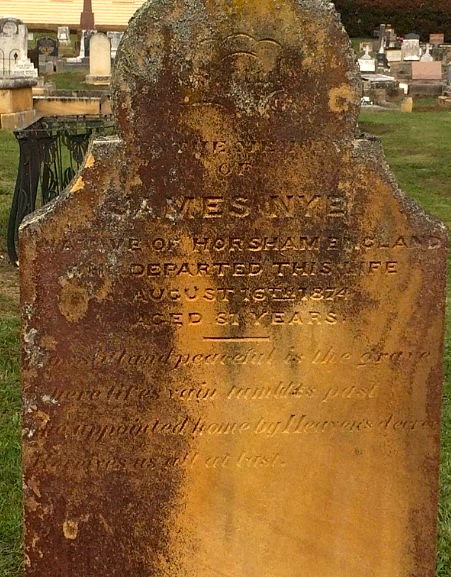

James lived to the age of 81 and was buried at the All Saints Anglican Cemetery in Sutton Forest.

His headstone reads:

James Nye

Native of Horsham England

Who departed this life

August 16th 1874

Aged 81 years

How still and peaceful is the grave

where life’s vain tumults past

The appointed home by Heaven’s decree

Receives us all at last.

Daniel Rapley

Daniel was a brickmaker and was assigned to Reuben Hannam, the overseer of government brickworks at Brickfield Hill in Parramatta. Reuben himself had been a brick and tile maker by trade. He may have felt some affinity with Daniel as he too had been sentenced to death in England and had his sentence commuted to transportation for life. Reuben’s wife and two children had been permitted to join him in Australia and he had been granted a Free and Unconditional Pardon.

Daniel applied for the Banns for his intended marriage to Mary Pike to be published in 1829. Reuben gave comments on Daniel’s character describing him as honest and industrious. Mary had been sentenced to 7 years’ transportation for larceny in 1827 and claimed she was a widow. However, remarks on the application stated she was a married woman whose husband, Joseph Pike, had been transported to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). The marriage between Daniel and Mary does not appear to have taken place.

Daniel was granted a Ticket of Leave in 1827 for the district of Sydney and a Conditional Pardon In 1834. By 1841, he was living at Surry Hills in Sydney.

He died on 18 September 1859 and was buried in Newtown in the city of Sydney.

Henry Jupp

After labouring on a government road party, Henry was “forwarded to Windsor for distribution” in January 1819. Windsor lies to the west of Sydney and to the east of the Blue Mountains.

In 1823, he was on the list of assigned prisoners and employed by Henry Pearce, a former convict and lieutenant in the British navy. Henry Pearce had been granted a Ticket of Leave for the Lane Cove district. A year later, Henry Jupp was assigned as a general servant to George Hawker, another former convict, at Kissing Point, Ryde. By 1828, he was employed in Castle Hill further to west of Sydney.

Henry was granted a Ticket of Leave in 1827 for the district of Kissing Point and a Conditional Pardon in 1834. He married Margaret Goodin or Goodwin in September 1829 after the birth of their first child, Lucy. Margaret had been born at Kissing Point as the daughter of a former convict. The couple had ten children and Henry managed his own farm at Kissing Point.

The Jupp’s property was badly affected by severe floods in 1856 which seemed to have troubled Henry for the remaining years of his life. He appears to have been afflicted by some form of dementia. His son, James, presented a petition to the Supreme Court in 1863 to find his father of unsound mind. The jury though returned a verdict to the effect that Henry was of sound mind.

Henry died on 22 August 1865 and was buried at Ryde Baptist graveyard.

William Brown

William Brown committed a new offence almost as soon as he arrived in Sydney and was sentenced to two years at the Newcastle penal colony, a secondary penal settlement to the north of New South Wales that was established to punish convicts who reoffended or were unruly. Records show that William was transported by sea from Sydney to Newcastle on the Lady Nelson on 1 February 1819. His fate is then open to speculation. The William Brown who arrived on the General Stewart cannot be traced on documents after that date and some sources state he died in Newcastle in 1822.

Henry Jupp did appoint a William Brown of Sydney as executor of his Will.

relationships to me

James Ewens was my 4x great granduncle and the sister of Hannah Ewens, my 4x great grandmother.

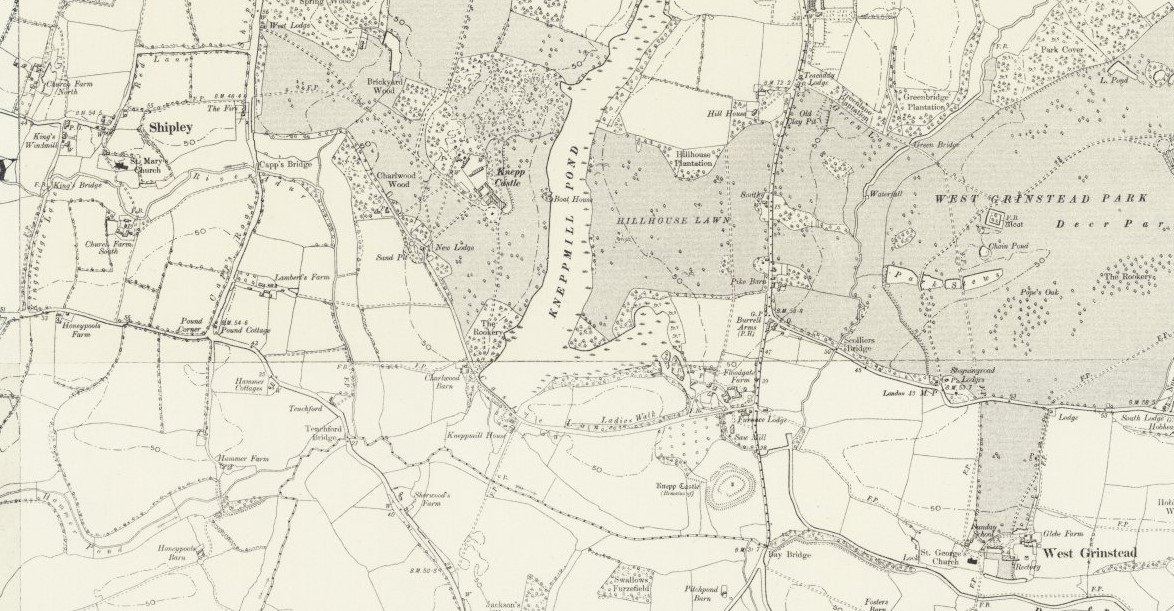

Hannah Ewens married Richard Turner, an agricultural labourer and gardener, at St Mary’s Church in Shipley in 1802. The leader of the Shipley Gang, James Rapley, lived in a cottage next to this church.

Richard Turner was great great grandfather to my paternal grandmother, Grace Dorothy Turner, and my 4x great grandfather.

Hannah (Ewens) Turner died in 1836. Richard Turner was living with two of his daughters close to the Rectory for St George’s Church in West Grinstead in 1841. He died on 2 April 1850 at the age of 72 and was buried at St George’s.

Gravestones for members of the Burrell family are in this graveyard. Magistrates, Sir Charles Merrick Burrell of Knepp Castle and Walter Burrell of West Grinstead Park were instrumental in the operation to capture the Shipley Gang.