Quarry Bank

A weird place is Quarry Bank.

In the language of the local authority, “the pits have took it in” until, at almost impossible angles, houses seem to stick together and the inhabitants live in them with mild concern, while an ordinary city man would be absolutely staggered at the thought.

Years ago it was a Black Country beauty spot, joined onto the Birch and Saltwells coppices.

But prosperity has left the place, and the mines have ruined the once trim and neat houses. Despair seems to have settled onto the inhabitants.

Birmingham Daily Gazette, 1906.

Nail Making

The hand-made nail trade in the Black Country had a long history that can be traced back to at least the Middle Ages. However, it never developed beyond a cottage industry during the course of the Industrial Revolution. Throughout the 19th century, nailing families suffered from low wages, control of pricing by the nail masters and the effects of regular strikes as both foreign competition and machine manufacture led to the slow death of the industry.

This article is taken from the Birmingham Daily Gazette in 1869:

THE CONDITION OF THE NAILERS

… One of the oldest industries of the Black Country – we mean that of nail making – is threatened with extinction. Within a distance of about fifteen miles – from Bromsgrove in the south to Sedgley in the north – there are about thirty thousand nailers, whose means of existence are now threatened with annihilation, by that all-powerful and unscrupulous innovator, the steam-engine. Reductions in the wages of the nailer have from time to time been made in consequence of the ever increasing competition from machine-made nails; and although those reductions have amounted within the last 25 years to about forty per cent., it is now contemplated to make a further reduction of ten per cent., and it is believed that the masters will be obliged to carry out their intention before the end of the summer. It is to be hoped, in the interest of common humanity, that this further step will not be found necessary, for the condition of the nailers is about as wretched and hopeless as can be conceived.

Nor can their condition be much wondered at, if their mode of living and working, and the wretched pittance they receive in exchange for their labour, are duly considered. Their homes are the type of untidiness and squalor; their children are allowed to run about the streets and fields half naked and hungry; some of them eking out a scanty living by stealing coal or gathering wood from the pit banks, tramways, or “coppices’’ in the neighbourhood, and then selling it to families one or two degrees higher in the social scale than themselves; their grown-up daughters and wives are universally brought up to the “block,’’ that is, to make nails, and hence have neither the time nor the inclination nor the ability do household work, and the consequence of the wretched catalogue of evils is, that the nailers are, as a rule, devoid of education, of social comfort, and of religious feeling. It is true that a few worthy men now and then go into their midst and reason with them, and endeavour to make religious impressions, and to lead them to a place of worship; but these efforts are attended with no permanent effect.

Their plan is play during the first two or three days the week, drinking away their money and their senses; and beginning to work on Thursday morning, they usually, in good times, work day and night, in order to be ready with their work at the warehouse on the Saturday afternoon, for “reckoning” time; and then, having received their wages according to the rates usually paid for the kind of work they deliver the warehouse, they recommence afresh the kind of life we have already described. …

The trade itself, however, seems to be in the last stages of its existence, and probably aware of this, all the promising young men, whose forefathers for generations have been nailers, are leaving the nail shop, and seeking employment in the ironworks. With regard to the first remedy suggested, it is admitted by all that the merchants who buy the work from the nailers cannot, under present circumstances, pay more for hand-made nails; but it has been suggested that persons with means, and with a desire to benefit the nailers, might be found, who, if a well-considered scheme could be devised, would be willing embark their capital in any enterprise having for its object either the introduction of nail making machinery to be worked the nailers themselves, or the introduction of some new industry which would absorb and find profitable employment for the rapidly increasing surplus population of the nail making districts.

Something should be done speedily. It is very little use talking or writing about “ education” unless artisans can be properly fed and clothed. If nail making cannot be made to pay, other trades pay. Then the sooner it comes to end the better for all concerned, so that at least there may be a chance of the present barbarous wretchedness among the nailers coming to end with the existing generation of that unfortunate class of operatives.

Birth

This is the world that Phoebe Stevens was born into. The marriage of her parents, my 3x great grandparents, Samuel Stevens and Phoebe Dunn, in 1838 was a typical Black Country union of its time – a coal miner to a nailer.

| relationship to me |

| Samuel Stevens and Phoebe Dunn (Stevens, Cole) – great great great grandparents |

| Sarah Stevens (Barnsley Nock, Wood) – great great grandmother |

| Phoebe Stevens (Bytheway, Raybould) – sister of Sarah Stevens, 2nd great grandaunt |

| Samuel Barnsley Nock – great grandfather |

| Gladys Barnsley – maternal grandmother |

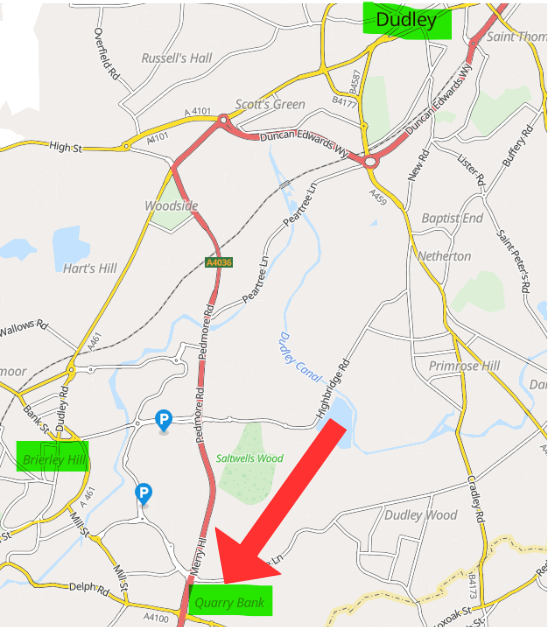

The Stevens lived in the hamlet of the Thorns in the parish of Quarry Bank. The History, Gazetteer and Directory of Staffordshire in 1851 recorded that,

Quarry Bank, Mount Pleasant, Crier’s Plain, and Thorns, are adjacent hamlets, about three miles South of Dudley, in the district parish of Quarry Bank, which has about 3000 souls.

Samuel and Phoebe had five known children:

- Mary (c. 1838)

- Noah (c.1839)

- Sarah (c. 1844)

- Phoebe (c. 1848)

- Sabra (c. 1850).

Noah died as an infant at the age of 2 and was buried at Brierley Hill on 11 December 1842.

His father, my 3x great grandfather, Samuel, died on 16 March 1853 from the effects of ileus (intestinal obstruction). He was 39 and his wife was left a widow at the age of 32.

Early Childhood

Phoebe was a nail maker making nails by hand. This involved working long hours doing repetitive, monotonous work in workshops attached to the home. Contemporary newspaper reports lamented half-fed workers living in extreme hardship, misery and poor sanitary conditions. Babies were taken into the workshop as their mother worked. Young children between the ages of 8 and 10 often entered the trade as bellows blowers, receiving little or no education. Infant mortality was high and women nailers continued to work while they were heavily pregnant, right up to giving birth and returning to the workshop shortly afterwards.

This excerpt describing childhood in a nailmaking family in the fictitious Black Country town of Quarrymoor is taken from “A Capful O’ Nails” written by David Christie Murray in 1896:

The forge in the back-kitchen was my earliest memory. I awoke permanently to a knowledge of the world whilst mother was working at the anvil. I was fixed in a sort of cloth bag upon her shoulders, and I remember peering round her neck at the glow of the fire, watching the iron rod as it came white-hot from the white-hot coke, and seeing her shape the end with dexterous blows into a nail, and then plunge the rod back into the fire again. It was raining at the time, and the splash on the roof made a dismal and sullen sound. I was hungry and I cried; but I was deeply interested for all that. Father came in wet and bare-headed, carrying in his hands a ragged cap full of coke, which he had bought or borrowed from a neighbour. I can see the place as I write. I can hear the tinkle of the hammer and its multiplied echoes from the cottages of our neighbours.

The nailer languished at the very bottom of the Black Country income scale and was seemingly exploited from all sides. The rolling mill made the rods of iron required for nail manufacture and master manufacturers sold bundles of these rods onto the nail makers. These bundles could contain rods that were unsuitable for manufacture and were often sold underweight. The nail maker carried the rods back home, manufactured the nails and then took the finished products back for sale. Then, s/he had to pay for the rent of the smithy, the costs of firing as well as tool making and repair. Foggers worked as middlemen supplying iron rods on credit and paying for finished nails in “truck”. Trucking was a system that existed in the Black Country long after it was made illegal which meant that nailers were not paid in cash but with a ticket for provisions from the tommy shop or public house at inflated prices.

David Christie Murray also described the fogger:

Here’s the fogger’s game wi’ the Black-Country nailer. To begin with, he’s got three sets o’ weights: a light set to buy with, a heavy set to sell with, and another set to show th’ inspector when he comes his rounds. He’s forbid by law to keep a tommy shop, but there ain’t a fogger in the countryside as hasn’t got a relation in that line o’ business. We’re forced to buy bad and dear, or woe betide us. When we buy for a certain size o’ nail, they sell us rods too thick for use, and charge us for changing them. They give us light weight, to begin with, and they lighten light weight till you’ve got sixpenn’orth for ninepence. When it comes to sellin’ the nails, they use the heavy weight, and they tek twelve hundred for a thousand. They’re not contented to take the wool, but they shave hide and all, and some of us are bound to ’em, soul and body.

Stepfather

My 3x great grandmother continued labouring nailing as a widow and bringing up her children for the next few years until she remarried a horse nail maker and widower, Thomas Cole, on 24 September 1856. Thomas had worked at nailing since his boyhood and had four children from a previous marriage to another nailer from Lye, Honour Round.

Life must have been hard but did not take a turn for the better for the Stevens children as their stepfather appeared at Staffordshire Quarter Sessions shortly before the 1861 census was taken. Thomas had stolen 56lbs of rod iron, the “property of Samuel Evers and others”, which he probably needed to carry out nailing or to sell to other nail makers.

Thomas pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 12 months’ hard labour at Stafford Gaol. His conviction noted that he had been previously convicted of a felon.

Major William Fulford, governor of Stafford Gaol from 1849 until his death in 1886, commented,

If I had the means of giving every man who is sentenced to hard labour in Stafford prison the full amount of discipline I am empowered to do by Act of Parliament, for two years, no man alive could bear it: it would kill the strongest man in England.

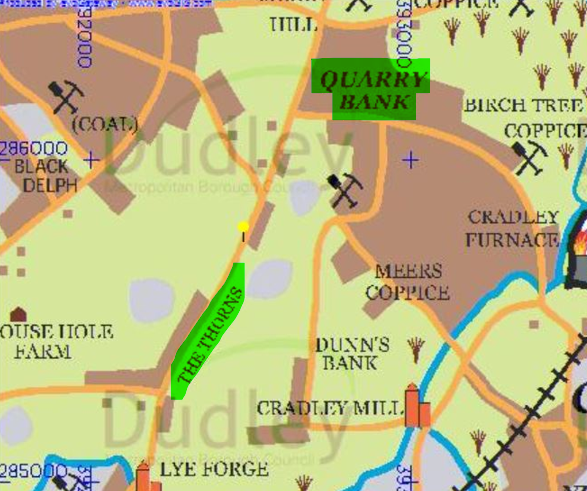

Hard labour punishments at Stafford included the crank, oakum picking, repairing the prison, breaking stone, pin-heading or the tread mill.

Accounts of the tread mill at Stafford alone testify to the harshness and severity of a hard labour sentence. The steps on the tread mill were 10 inches high and a prisoner were required to climb 57 steps per minute for six hours a day, climbing for 16 minute stints with eight minute rests in three two-hour shifts. Prisoners climbed 11,395 feet a day, or almost two thirds of the climb to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro, on a diet of oatmeal gruel, bread and water and a pint of soup a week.

Thomas would have not been allowed contact with his family for the first part of his sentence and it is difficult to imagine that he or his family would have had the means to do so in any case throughout the period of his sentence.

A Nailer at 13

As Thomas entered prison, his wife was pregnant with a further daughter, Comfort Cole, and living on Sheffield Street in Quarry Bank. The 1861 census recorded her daughter, Phoebe Stevens, was then 13 and working as a nailer. The household also included the children from her husband’s first marriage:

- Elijah Cole (10, a chain maker)

- Bettey Cole (8)

- Emma Cole (7)

- Honour Cole (5).

Thomas would have left prison in 1862 and this article gives some impression of the ongoing working conditions for the Cole family:

Buchan Observer and East Aberdeenshire Advertiser, November 1880.

NAIL MAKING IN THE BLACK COUNTRY

A correspondent of the Daily Telegraph is among the nail workers in the Black Country and he thus describes a workshop and its inmates. When I arrived at the door of the first little smithy and looked in I found it to be no larger than an ordinary washhouse – about 10 feet by 10 but it was made to contain two forges and three anvils. Busy at work at them was an elderly man, his wife, and a grown daughter – a muscular young woman of about eighteen. The father was making nails for horseshoes, and the old woman and the young one were hammering away at nails of a lighter kind. The horse-nail maker was a red-nosed, dissipated-looking old rascal, his sole attire being a ragged pair of trousers and a raggeder shirt – who smoked his pipe while he worked, and drank frequently from a can of beer that never travelled a foot from his side of the forge. The elderly woman was a poor, starved-looking creature, as ragged comparatively as her husband, and her gray hair was bound about with a wisp of dirty rag. Her sinewy old arms were bare to the shoulders, and her hands knotted and corned. She wore a leather apron like a regular blacksmith, and, completing the oddity of her appearance, her eyes were protected with a pair of brass-rimmed spectacles. The young woman was bare-armed to the shoulders, like her mother, with a face as smutty as her father’s, but her hair was cut with a fashionable ‘ fringe,’ and as she hammered away at the glowing iron on her anvil, a pair of earrings twinkled in her ears. I made sonic apology to the horse-nail maker for looking in, to which he replied with a laugh, and draining his beer-can, that I had best stand a quart and say no more about it. The moment I handed him the necessary sixpence I saw that I had done a wrong thing. No, no; don’t go out old lad,’ pleaded his wife, as the man threw down his hammer, and pulled on his old cap. “Let ‘Becca fetch it. Thoul’t never finish thy thousand by the morning if thou doesn’t stick to ’em a bit.’ But the ‘old lad’ took no heed and walked off. “That’s the last we shall see of him to-night”, remarked the old woman, sadly. “Good job too, responded the daughter, as she hammered viciously at a nail. He’s better off anywhere than cussing and swearing here. He knows that while he’s idling we’re a-slaving; and more foul us. What do you say, sir?

Marriage

The Stevens daughters married in succession, before and after Thomas was in prison:

- Mary married Alfred Bullock, an iron labourer and roller, in 1859.

- My great great grandmother, Sarah, married Josiah Barnsley Nock, a chainmaker, in 1864.

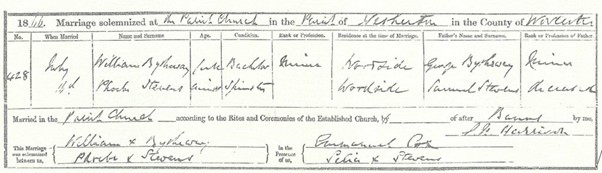

- Phoebe married William Bytheway, a coal miner, on 16 July 1866. She was 18 and pregnant with her first child, George, who was born at the end of the same year.

- Her sister, Sabra married Emmanuel Cox, a horse nail maker who went on to run a shoe shop on Quarry Bank High Street, later in 1866.

The Bytheways moved to Maughan Street in Quarry Bank, a few doors from my Barnsley Nock great great grandparents.

Phoebe gave birth to:

- son George in 1866

- daughter Martha on 15 August 1868

- son Noah on 22 August 1870

- daughter Emma on 20 September 1871.

Phoebe was thus pregnant for over half her life from the age of 17 to 23.

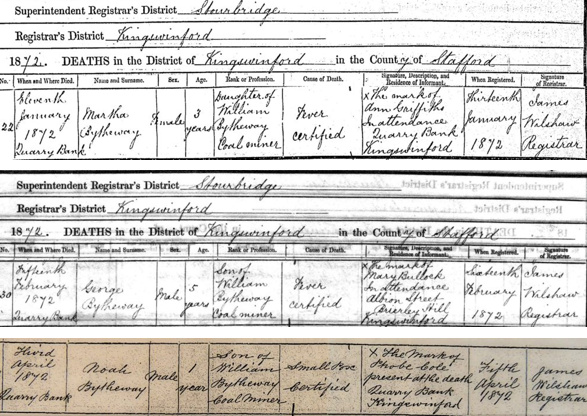

Three of the four Bytheway children died within a period of three months at the beginning of 1872:

- Martha on 11 January at the age of 3 – cause of death “fever certified”

- George, just five weeks later on 15 February, at the age of 5 – the cause also “fever certified”

- Noah aged 1 on 3 April – cause of death small pox.

Just five months after experiencing this quick sequence of her children’s deaths, Phoebe was pregnant once again. Her daughter, Mercy, was born on 12 June 1873 but had epilepsy and was deaf. Neither of these conditions are related to mental health issues today but Mercy was dubbed both a “lunatic” and “idiot” on census returns.

Further children followed:

- William born on 5 June 1875

- Joseph born on 10 June 1877

- Benjamin born on 9 July 1881

by which time the family was living at Merry Hill.

- Elise Annie born on 11 July 1884

- Daniel born on 23 September 1886.

Stealing Coal

Phoebe appeared before Brierley Hill police court on 6 November 1879 and 23 October 1882 on the charge of stealing coal and was fined in both cases.

In the first instance, she was fined 3s 6d together with her neighbours, Eliza Hazlewood and Susannah Shaw, her sister, Sarah Barnsley Nock, Emma Hampton and Sarah Turley, her neighbours on Maughan Street, and another woman from Quarry Bank, Esther Bloomer. The women were charged with stealing coal from the Earl of Dudley’s Wallace Colliery at Merry Hill and undermining the railway to get to the coal. Parts of the Merry Hill shopping centre are built are on the site of Wallace Colliery today.

On the second occasion, Phoebe, Susannah Smith and Selina Deeley were caught stealing coal from Caleb Roberts and another and fined 5s.

Sheffield Street

Red X: Oak Street. Yellow X: Victoria Road. Green X: Sheffield Street. Blue X: Z Street. Grey arrow: High Street.

Phoebe’s half sister Comfort Cole, died on 17 November 1879 at the age of 19, just a few days after Phoebe appeared in court. Comfort had married Enoch Bradbury, a miner, earlier that year and given birth to a child, Albert. Albert went on to live with Comfort’s parents, Phoebe and Thomas Cole, on Sheffield Street after his mother’s death. He only survived her by 16 months though and died on 10 April 1881.

Sheffield Street was recorded as having around a hundred houses in 1890 where not one single adult could read or write. George Dunn, a chainmaker and “the Minstrel of Quarry Bank”, was born on the street in 1887 and his memories of Quarry Bank testify to the ongoing hardship of women’s lives:

There was nobody in the ‘ouse when I was born except me mother. The midwife, who resided with us, were out on another case and before she came back I was borned. I was born on the floor and ‘er [his mother] was on the floor. ‘Er was on the floor a lung, lung time before somebody come into th’ouse to fetch the midwife. When I was born I got starved to death and I’ve never got bloody warm since.

My mother’s breed o’ women, they’m only little uns, but they were brave as lions. The wife wouldn’t leave ‘er kids. I’ve seen some terrible things ‘appen to women. I’ve seen men ‘alf kill ’em, only barely left ’em alive, but they wouldn’t forsake their kids. The struggle to rear the kids, yo’ cort imagine ‘ow ‘ard it was. It beggars the imagination. We used t’ave a lot more dinner times than dinners where we’m bin reared.

‘Er used to bake ‘er own bread, and 90 per cent did. They’d all got a little oven in the brew ‘ouse. I’ve known it when money’s bin short, and it was short mostly at th’end o’ the week. We’d got a job to make it last, you know, ’cause they never knew what they were a-goin’ t’ave on the Saturday. If they ‘ad a pound, and there was nine on us to keep – there was no trouble that wik.

Widowed

William Bytheway, Phoebe’s husband, worked at Homer Hill Colliery, a coal mine located near Cradley Forge and owned by S. Evers & Sons, by a twist of fate the same Evers company who owned the rods stolen by Phoebe’s stepfather.

A brusher, William cut or blasted the roof or floor of a roadway in the pit to give it more height or blasted stratas above and below worked seams to form roadways. On 23 April 1890, a horse pulling a full tub of coal underground in the mine suddenly started. The tub overturned and the full tub of coal fell on William who died of his injuries the next day. An inquest held on 28 April determined that he had died due to “accidental fractures by a tub in a coal mine.” Phoebe, like her mother before her, was left a widow.

The census of 1891 recorded Phoebe living on Oak Street as a widow with her seven children, the last year that the surviving Bytheway siblings lived together under the same roof.

- Emma married Charles Kendrick the following year and moved to Birmingham, where Charles worked for Birmingham Corporation as a tram conductor.

- Mercy died from tuberculosis and the effects of her epilepsy on 8 January 1899.

By September 1896, Phoebe was living on Bower Lane when she got engaged to a man called Flavell who was “advanced in years”. Flavell’s son, Thomas, a blacksmith in Quarry Bank, did not agree to the marriage and met Phoebe on Mill Street in Brierley Hill. He “brutally assaulted” her. Phoebe again appeared at the police court in Brierley Hill but as a defendant this time. She was awarded £5 compensation, £1 1s solicitor’s fees, £1 1s doctor’s fees and court costs. Thomas Flavell was also bound over to keep the peace for 6 months and had to promise not to molest Phoebe again. She did not go on to marry his father.

Marriage

Phoebe did remarry in 1900. Her second husband, Thomas Raybould, an iron worker and shingler, was a widower with 7 children, the youngest of whom was 9 at the time of the marriage to Phoebe. Nailing was no longer an occupation of anyone in the family, reflecting the decline in the industry and the general movement of labour to chain making and iron working in Quarry Bank.

The houses on the right towards the top of the street were built after 1903.

Annie Glaze was the licensee of the Fountain Inn from 1897-1908 and 1909-1921 after the death of husband, George, at Stour Colliery.

In 1901, the Rayboulds were living at 39 Victoria Road together with Phoebe’s sons:

- William Bytheway (26), a clay miner and loader

- Daniel Bytheway (14)

and Thomas’ sons:

- John Thomas Raybould (19), a blacksmith striker

- Charles Raybould (14).

The Rayboulds also had two lodgers, Mary Elizabeth and Francis George Gittins, the widowed mother and brother, of Benjamin Bytheway’s future wife, Florence Beatrice Gittins.

Phoebe’s other children had all moved to 16 London Road in Handsworth, Birmingham, the household of their sister, Emma. Joseph was a tram conductor for Birmingham Corporation, Benjamin a blacksmith striker and Elsie a press worker as was Florence Gittens, then 16, boarding in the same household.

Murder

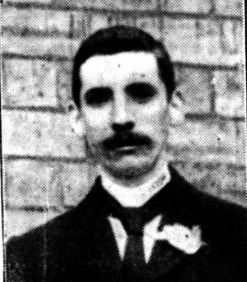

Towards the end of 1906, Victoria Road in Quarry Bank attracted attention from the nationwide press. Joseph Jones, a former stocktaker and weigher at an ironworks, his daughter, Ethel, son in law, Edmund Clarke and three young grandsons lived at number 18, a few doors from the Rayboulds at number 39.

Joseph had been irregularly employed for around two years and had signed over the mortgage on the house at number 18 to his son-in-law, Edmund. This caused resentment and arguments as Joseph became dependent on his son-in-law and daughter. Reports also stated that Joseph drank, really not an uncommon fact in Quarry Bank at the time. He became convinced that his son-in- law wished to remove him from his own home. Edmund, 26, was reputedly an upstanding member of the community. A Sunday School teacher, he was was building his own haulier business.

On December 1, a Saturday, Edmund returned to Victoria Road after taking local footballers to a game in his wagonette. Stating he was tired, he fell asleep on the sofa underneath the kitchen window. It was around 8.45pm and Ethel left the house to go the butchers, presumably on the adjoining High Street. When she came back about half an hour later, the house was locked and she had to get her father to open the door. Joseph muttered that Edmund had “started on him”, pushed past his daughter and walked up to the Vine Inn, then on the corner of the High Street and Victoria Road.

Ethel was met with a horrific scene. Witnesses afterwards stated that the kitchen resembled a slaughterhouse. Edmund was lying, still barely alive, against the fireguard with his feet towards the door. The floor, sofa and walls were covered in blood. Ethel ran out of the house screaming murder and in the meantime Joseph gave himself up to a police constable confirming he had hit his son-in-law with a poker. In fact, he had caved Edmund’s head with the poker by striking him with several blows and had then attempted to slit Edmund’s throat with three different razors.

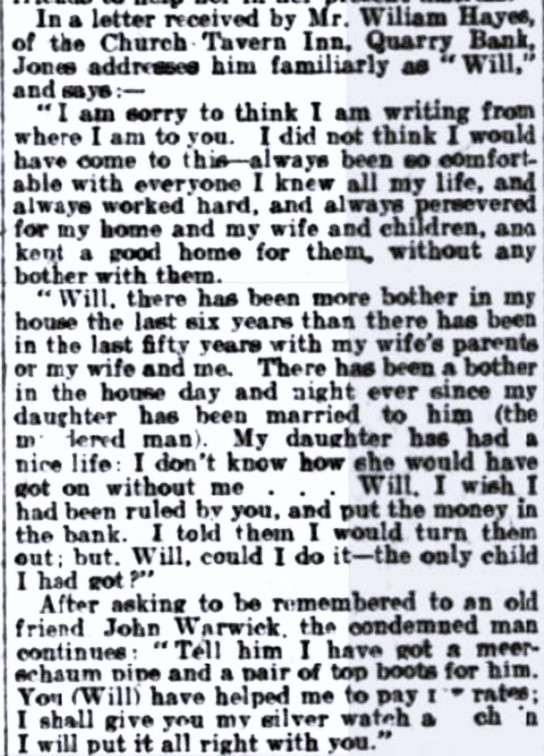

Newspapers reported women gathering to make protests against Joseph when he was taken into custody in Brierley Hill. He was then remanded to Winson Green jail and found guilty of murder at Staffordshire Assizes on 7 March 1907. Although the jury made a recommendation for mercy, Joseph was sentenced to death and hanged at Stafford Gaol by Henry Pierrepoint on 26 March.

The press stated that the murder had thrown Quarry Bank into a state of intense excitement. Edmund’s funeral was a major occurrence that took the cortège down Victoria Road to Edmund Clarke’s sister’s home at 33 Victoria Road and then to the cemetery that lies at the end the road. Phoebe would certainly have been acutely aware of the murder. Nevertheless, there were other events around the same time that might have had a more devastating personal effect.

Emigration

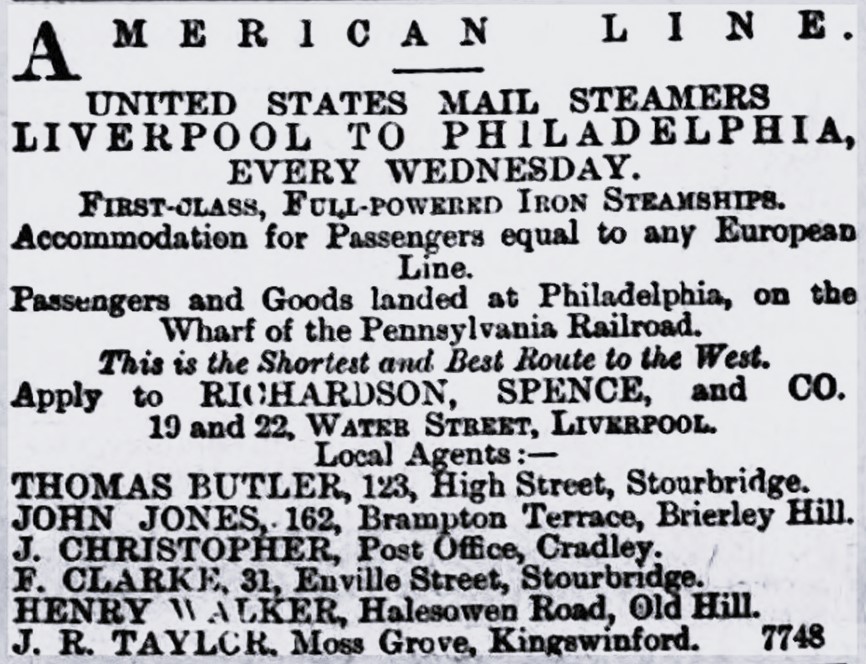

Phoebe’s eldest son, William Bytheway married Jessica Morris towards the end of 1903 and in the following year took the decision to emigrate to the United States, leaving Liverpool on 1 September and arriving in New York two weeks later.

William settled in the coal mining town of Moosic in Lackawanna County, Pennsylvania and resumed working as a coal miner. Positive reports must have got back to the Bytheway siblings since Benjamin and Joseph together followed William to Pennsylvania’s coal mines in 1906 after their respective marriages to Florence Gittins and Emma Cartwright. Their step sister, Dinah Raybould, her husband John Benson and young family, emigrated to Moosic in 1910.

There must have been factors that attracted different members of the family to emigrate with their families to the States but it is difficult to believe that the conditions in the coal mines in Pennsylvania were a great deal better than those in the Black Country. Lewis Hine’s photographs taken between 1908 and 1924 in Pennsylvania and other coal mining areas helped to change child labour laws in the States. They are testimony to the facts that working life was tough and emigrating to America did not necessarily represent a move to any kind of workers’ paradise. Indeed, both William and Benjamin must have become unemployed by 1940 as they were then labourers on WPA (Works Project Administration) projects, a government scheme devised by President Roosevelt during the Great Depression to provide employment on public works and infrastructure.

Z Street

By the time of the 1911 census, Phoebe no longer had any children or grandchildren that lived in the close vicinity as they had moved to Birmingham, emigrated or been born outside the Black Country.

Thomas and Phoebe Raybould had moved to 23 Z Street in Quarry Bank. They were living together with Thomas’ son, Charles, then 20 and a labourer. The couple stated they had had no children themselves but crossed this out and entered the number one. No evidence of a birth of a child to the couple has been found to date however.

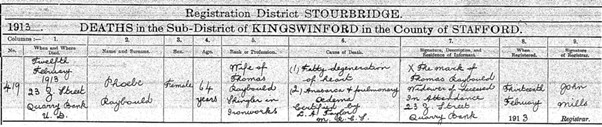

Phoebe died at the age of 64, then considered an old age. Joseph Jones, the murderer at 18 Victoria Road, was invariably designated “old” or “elderly” in the press and he was 60. Thomas Raybould was present at his wife’s death at 23 Z Street on 12 February 1913. The causes of the death were given as fatty degeneration of the heart and anarsca odema, a swelling of the skin by fluids.

Final Words

If Phoebe’s life story were written in fiction today, the plot outline could seem too far-fetched for the most melodramatic soap opera:

born into an inescapable poverty trap – loss of father – no education – illiterate child labourer – stepfather in prison – teenage pregnancy – loss of 3 infant children in a period of 3 months – in trouble with the police – loss of first husband in a work accident – a “lunatic” child – assaulted – three sons who emigrated – grandchildren who were never seen.

It is not possible to layer Phoebe’s story with her emotions, give details of her character or even to know what she looked like. Nevertheless, such aspects must have been shaped by an environment in which men, women and children did hard physical dangerous jobs, struggled to put food on the table and lived in a culture of hard drinking and violence. Phoebe almost certainly never read a book or learnt to write her name. The lack of opportunity that she faced in her life is in sharp contrast to the world of opportunity offered to my generation and yet Phoebe’s life only lies four generations back in my family history.

What incredibly rich stories! I love how you find connections with the wider context. It makes me think about what types of stories are recorded and traceable – industry and crime. What if our ancestors passed on stories about nature and their connection with it? What stories will future generations be able to trace of our lives? What types of stories might they want to know?

Thanks for the feedback. Food for thought … Holly!

What a beautiful storytelling gift to pass on Erica. I particularly loved your description of your motivation “I quickly discovered that I was not satisfied with lists of dates, names and places but that I wanted to know more about the lives my ancestors had led – to walk in their steps and follow their storylines in space and time.”

Thank you for the lovely comments Jo – very much appreciated!