from good American stock

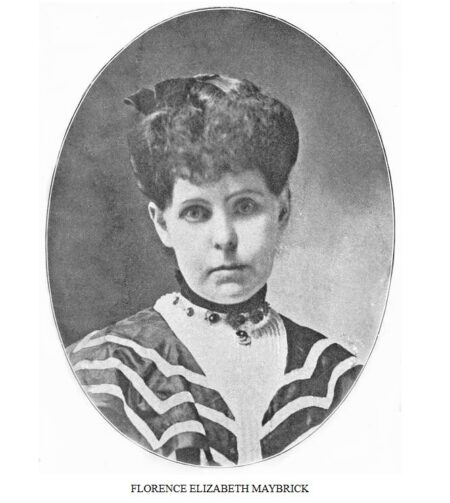

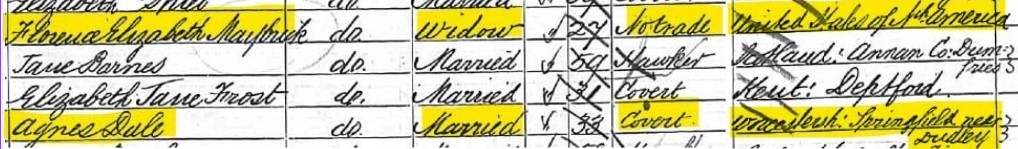

The trial and conviction of Florence Elizabeth Maybrick was the subject of both international and national newspaper headlines in 1889. Her case continues to spark debate today.

Born in Alabama in the United States, Florence descended on both her ‘paternal and maternal side for generations from good American stock’ and was the daughter of William George Chandler, the son of a lawyer and a partner in a banking house, and Caroline Elizabeth Holbrook.

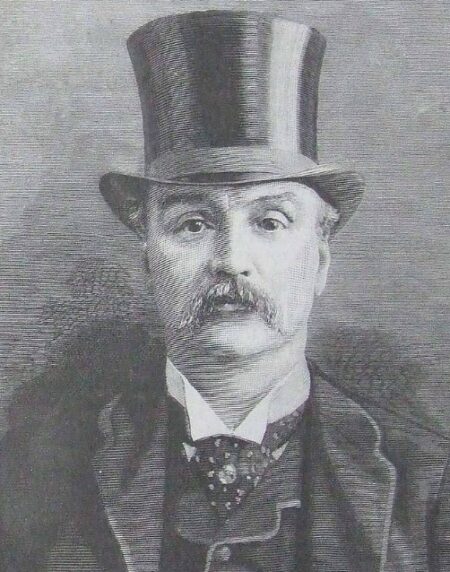

At the age of 18, she married James Maybrick, a cotton merchant from Liverpool and 23 years her senior. The couple lived in Virginia and then in Liverpool at Battlecrease House at 7 Riversdale Road in the suburb of Aigburth.

The marriage was not a happy one. James had several mistresses, was prone to violence and a hypochondriac who regularly used medicines containing strychnine, phosphoric acid or arsenic. In spring 1889, his health deteriorated as he took a dangerous mixture of medicines and poisons, including twenty separate doses alone in the week before his death at Battlecrease House on 11 May. His body was found to contain slight traces of arsenic.

Florence was suspected by members of her husband’s family and some of the domestic staff. She was accused of soaking fly paper to extract the arsenic and bottles of meat juice were found that had been contaminated with arsenic. A letter she wrote to Alfred Brierley, a cotton merchant with whom she was having an affair, was intercepted by a nursemaid and taken as a motive for murder.

Florence was taken into custody and held at Walton Jail, now Liverpool Prison, until she went on trial at St. George’s Hall in Liverpool on 31 July. She was found guilty and sentenced to death.

from the Black Country

During this same period Agnes Dale was taken into police custody in London on 20 July and subsequently arrested on 3 August.

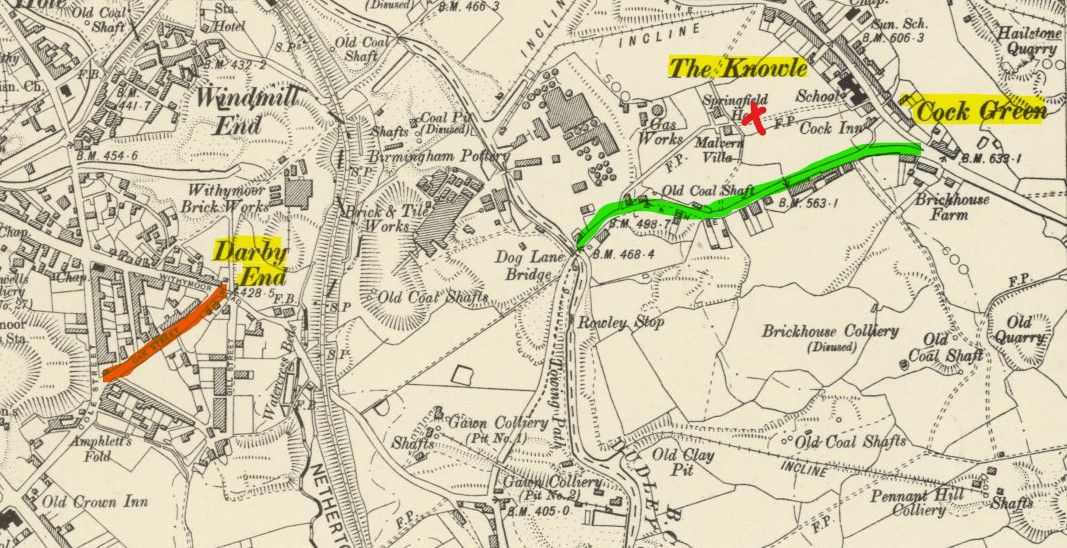

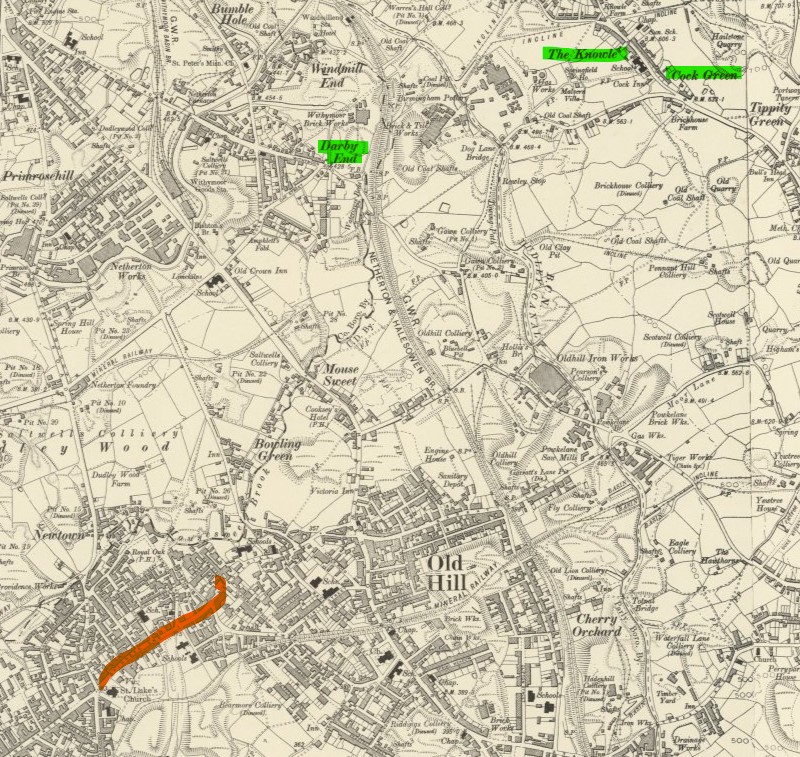

Florence and Agnes had been shaped by very different cultural and social backgrounds. Agnes’ father, Thomas Grove, was a labourer and her mother, Eliza (Priest), a nail maker in the hamlets of Knowle and Cock Green – Rowley Regis – in the Black Country.

Agnes Grove was pregnant with her first child, George Grove Dale, when she married George Dale on 6 July 1879.

George Dale was the youngest child of a farmer and baker in Adderbury, a village near Banbury in Oxfordshire. He had moved to Wolverley near Kidderminster by 1871 where he registered his occupation as an assistant in a chemist and tobacco shop. After their marriage, Agnes and George lived at Darby End and had three more children, the youngest of whom was born at Spinners End and baptised at Redhall Hill in May 1885. George registered his occupation as a grocer’s assistant.

to London

By this time Agnes’ younger sister, Ruth, had sought employment in London as a domestic servant and ‘nurse’ in the household of James Hart, a law clerk, on Oxford Street in Putney.

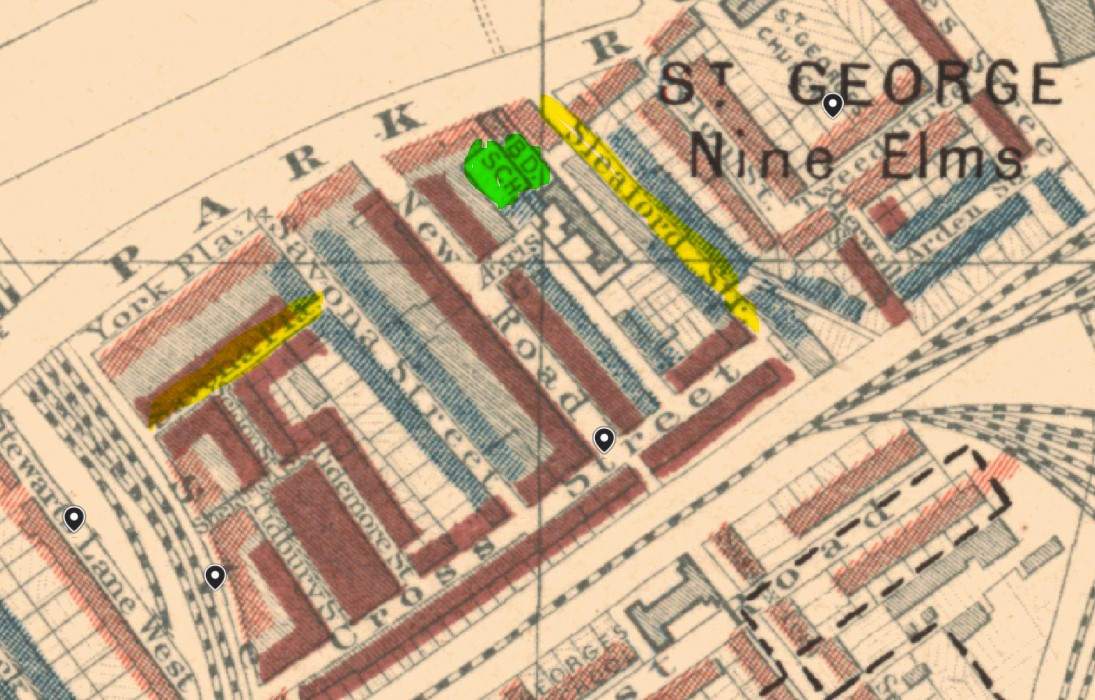

The Dales followed Ruth to London in 1887 when two of their children, Agnes Lily and John Thomas, were registered at Sleaford Street School in Battersea in February after attending a ‘church school in Dudley’.

Agnes’ youngest sibling, Lot, also made the move to London and was a witness at Ruth’s marriage to George Edwards in Wandsworth in 1888. He married Maria Carter in 1889 when he was living in Lambeth and employed as a shunter for the London and South Western railway.

Agnes and George Dale made their London home at Nine Elms in Battersea. Today this area lies directly behind Battersea Power Station, a fashionable leisure, shopping and residential area. The Dale family resided on Savona Place and then Sleaford Street, streets were designated as areas of poverty in Charles Booth’s 1889 descriptive map of London poverty in which Booth coloured each street to show the social class and income of the residents.

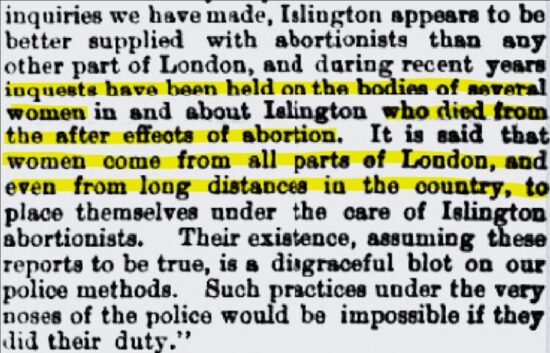

Agnes and George continued a practice they had established ‘at Birmingham’ until their arrests in 1889. They had built an extensive trade by charging women five shillings – around £40 today – for a back street abortion. The couple were experienced but clearly unqualified.

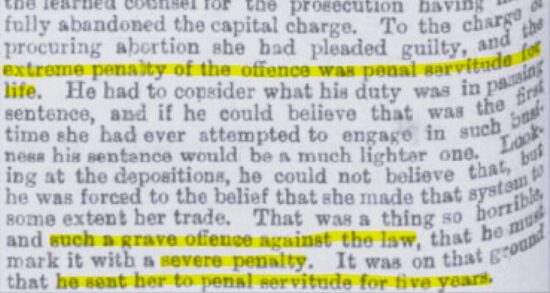

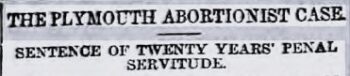

Abortion was illegal in Victorian England and the courts tended to hand out heavy sentences to abortionists.

Section 58, Offences Against the Person Act, 1861

Every woman, being with child, who, with intent to procure her own miscarriage, shall unlawfully administer to herself any poison… or unlawfully use any instrument… shall be liable to be kept in penal servitude for life.

Exact statistics on numbers are impossible to find as abortion was concealed and euphemisms – ‘female pills’, ‘remove an obstruction’ – were common but various sources conclude its use was widespread. George Dale’s profession as a grocer or chemist’s assistant may indicate his early and long lasting involvement with abortion. Lesley Hall of University College London claims that such shops sold pills and remedies and if these failed then offered a back street abortion.

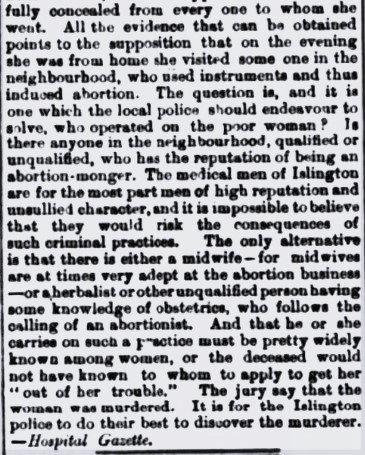

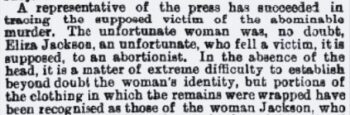

Many miscarriages and a number of fatalities must have been as a result of back street abortions or taking pills and drugs.

Both Agnes and George were arrested on two charges of ‘using a certain instrument’ to procure the miscarriage of Annie Elizabeth Smith and detained on the same offence to procure the miscarriage of four further women – Elizabeth Haywood, Elizabeth de Winton, Harriet Bowers and Sarah Bailey. Two of these women can be traced.

Both were married women from working families who probably wanted to avoid having more children. Harriet Bowers (Penston) was a near neighbour of Agnes’ and lived on Savona Street. By 1889, she had been married for nine years to a labourer who worked on the railway and had given birth to four children. Elizabeth de Winton (Daniels) had been born in Battersea and married Aubrey de Winton, a stone mason, when she was 18. In 1889, she had also been married for nine years and had had three children.

It was very seldom that women appeared in court accused of procuring their own abortions. … If, however, a woman came under medical surveillance in mortal extremity following an operation performed by an abortionist or involving instruments, there might be endeavours to make her give up the name of any person who had aided her. (Lesley Hall).

to prison

George and Agnes appeared at the Old Bailey, London’s central criminal court, on 16 September charged with ‘using certain instruments for an unlawful purpose’. Later registers recorded that Agnes was just under 5ft tall with dark brown hair and eyes. She must have seemed a diminutive and perhaps sorry figure in the Old Bailey courtroom.

The couple pleaded guilty with the defence claiming that they were ‘ignorant persons and totally unaware of the serious character of the offence’. George was sentenced to ten years’ penal servitude and Agnes to five years. On hearing the sentence, Agnes fainted and had to be carried downstairs in an unconscious state.

Florence Maybrick had learned on the day of her planned execution that her sentence had been commuted to life imprisonment and she was transported from Liverpool to the female convict prison at Knaphill in Woking on 29 August. She became convict L.P. 29. L stood for life, P for the year of conviction and 29 for being the twenty-ninth convict of the year. Shortly afterwards Agnes Dale became P 31 at Woking and the contrasting lives of these two women converged behind prison bars.

prison life

Florence Maybrick published her story, My Fifteen Lost Years, in 1905. Her account gave substantial detail of her imprisonment at Woking, mirroring Agnes Dale’s experiences.

Florence described three stages to her imprisonment at Woking.

solitary confinement

Here is one day’s routine: It is six o’clock; I arise and dress in the dark; I put up my hammock and wait for breakfast. I hear the ward officer in the gallery outside. I take a tin plate and a tin mug in my hands and stand before the cell door. Presently the door opens; a brown, whole-meal, six-ounce loaf is placed upon the plate; the tin mug is taken, and three-quarters of a pint of gruel is measured in my presence, when the mug is handed back in silence, and the door is closed and locked. After I have taken a few mouthfuls of bread I begin to scrub my cell. A bell rings and my door is again unlocked. No word is spoken, because I know exactly what to do. I leave my cell and fall into single file, three paces in the rear of my nearest fellow convict. All of us are alike in knowing what we have to do, and we march away silently to Divine service …Chapel over, I returned directly to my cell …

My task for the day is handed to me, and I sit in my cell plying my needle, with the consciousness that I must not indulge in an idle moment, for an unaccomplished task means loss of marks, and loss of marks means loss of letters and visits. As chapel begins at 8:30 I am back in my cell soon after nine, and the requirement is that I shall make one shirt a day – certainly not less than five shirts a week …

Then comes ten o’clock, and with it the governor with his escort. He inspects each cell, and if all is not as it should be, the prisoner will hear of it. …

Presently, however, the prison bell rings again. I know what the clangor means, and mechanically lay down my work. It is the hour for exercise, and I put on my bonnet and cape. One by one the cell doors of the ward are opened. One by one we come out from our cells and fall into single file. Then, with a ward officer in charge, we march into the exercise yard. We have drawn up in line, three paces apart, and this is the form in which we tramp around the yard and take our exercise. This yard is perhaps forty feet square, and there are thirty-five of us to expand in its “freedom”. …

When the one hour for exercise is over, in a file as before, we tramp back to our work. Confined as we are for twenty-two hours in our narrow, gloomy cells, the exercise, dull as it is, is our only opportunity for a glimpse of the sky and for a taste of outdoor life, and affords our only relief from an otherwise almost unbearable day.

At noon the midday meal. The first sign of its approach is the sound of the fatigue party of prisoners bringing the food from the kitchen into the ward. I hear the ward officer passing with the weary group from cell to cell, and presently she will reach my door. My food is handed to me, then the door is closed and double locked. In the following two hours, having finished my meal, I can work or read.

At two o’clock the fatigue party again goes on its mechanical round; the cell door is again unlocked, this time for the collection of dinner-cans…. From that time on until seven o’clock more work, when again is heard the clang of the prison bell, and with it comes the end of our monotonous day. I take down my hammock, and once more await the opening of the door. We have learned exactly what to do. With the opening of our cells we go forward, and each places her broom outside the door … On through the ten long, weary hours of the night the night officers patrol the wards, keeping watch, and through a glass peep-hole silently inspect us in our beds to see that nothing is amiss. …

probation

I was taken from Hall G to Hall A. There were in Woking seven halls, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, separated by two barred doors and a narrow passage. Every hall has three wards.

The female warder who accompanied me locked me in my cell. I looked around with a sense of intense relief. The cell was as large again as the one I had left. The floor was of wood instead of slate. It contained a camp bedstead on which was placed a so-called mattress, consisting of a sack the length of the bed, stuffed with coir, the fiber of the coconut. There were also provided two coarse sheets, two blankets, and a red counterpane. In a corner were three iron shelves let in the wall one above the other. On the top shelf was folded a cape, and on top of this there was a small, coarse straw bonnet. The second shelf contained a tin cup, a tin plate, a wooden spoon, and a salt cellar. The third shelf was given up to a slate, on which might be written complaints or requests to the governor; it is a punishable offense in prison to write with a pencil or on any paper not provided.

There was also a Bible, a prayer book and hymn book, and a book from the library. Near the door stood a log of wood upright, fastened to the floor, and this was the only seat in the cell. It was immovable, and so placed that the prisoner might always be in view of the warder. Near it, let into the wall, was a piece of deal board, which answered for a table. Through an almost opaque piece of square glass light glimmered from the hall, the only means of lighting the cell at night; facing this, high up, was a barred window admitting light from the outside.

The routine of my daily life was the same as during “solitary confinement.” The cell door may be open, but its outer covering or gate is locked, and, although I knew there was a human creature separated from me only by a cell wall and another gate, not a whisper might I breathe.

hard labour

I was permitted to leave my cell to assist in carrying meals from the kitchen, and to sit at my door and converse with the prisoners in the adjoining cells for two hours daily – but always in the presence of an officer who controls and limits the conversation.

My daily routine was now also somewhat different from that of solitary confinement and probation.

At six o’clock the bell rings to rise. Half an hour later a second bell signifies to the officers that it is time to come on duty. Each warder in charge of certain wards – there are three wards to each hall – then goes to the chief matron’s office, where she receives a key wherewith to unlock the prisoners’ cells. All keys are given up by the female warder before going off duty, and locked for the night in an iron safe under the charge of a male warder. When again in possession of her key she repairs to her ward, and at the order, “Unlock,” she lets out the prisoners to empty their slops. This done, they are once more locked in, with the exception of three women who go down to the kitchen to fetch the cans of tea and loaves of bread which make up the prisoners’ breakfast. …

The breakfast was served at seven o’clock, when the officers returned to the mess-room to take theirs. At 7:30 a bell rang again, and the officers returned to their respective wards. At ten minutes to eight the order was given, “Unlock.” Once more the doors were opened. Then followed the order, “Chapel,” and each woman stood at her door with Bible, prayer book, and hymn book in hand. At the words “Pass on,” they file one behind the other into the chapel, where a warder from each ward sits with her back to the altar that she may be able the better to watch those under her charge and see that they do not speak. After a service of twenty minutes the prisoners file back to their cells, place their books on the lower shelf, and with a drab cape and a white straw hat stand in readiness for the next order, “To your doors.” This given, they descend into the hall and pass out to their respective places of work. …

The work for first offenders, who are called the “Star Class,” consists of labor in the kitchen, the mess, and the officers’ quarters. Six months after I entered upon the third stage I was put to work in the kitchen. My duties were as follows: To wash ten cans, each holding four quarts; to scrub one table, twenty feet in length; two dressers, twelve feet in length; to wash five hundred dinner-tins; to clean knives; to wash a sack of potatoes; to assist in serving the dinners, and to scrub a piece of floor twenty by ten feet.

Besides myself there were eight other women on hard labor in the kitchen. Our day commenced at 6 A.M., and continued until 5:30 P.M. A half hour at breakfast time, twenty minutes at chapel, one hour and a half after the midday meal, and half an hour after tea summed up our leisure. The work was hard and rough.

Agnes Dale was granted a prison licence on 4 April 1892 and released on licence conditions to the address of her brother, Lot, at 15 Portslade Road in Wandsworth. Licence conditions meant that Agnes was released to spend the remainder of her sentence outside prison under certain conditions.

Florence Maybrick was transferred to Aylesbury prison in November 1896 and finally released in January 1904.

George Dale was confined at Portland Prison and later transferred to Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight. He served seven and a half years of his sentence and was discharged from Parkhurst as an habitual criminal on 8 March 1897, his address given as 29 Brooke Street in Holborn with his occupation as a baker. Registered in the Metropolitan Police Register of Habitual Criminals, he was described as 5ft 3¼ins tall with a fair complexion, brown hair and grey eyes.

to Oxfordshire

George and Agnes were living as husband and wife on Loughborough Road in Lambeth in 1901 with George an employer and coffee stall keeper. Ten years later, George was an assurance agent and living on Anstey Road, Herne Hill with his daughter, Lilly, and two boarders. Agnes’ whereabouts at the time are not known.

By 1921, the couple had relocated to Bucknell in Oxfordshire, the county of George’s birth. George was a master grocer, perhaps an indication that he had resumed his activities as an illegal abortionist. Agnes and her sister, Ruth, eventually settled in Wendlebury, a village in Oxfordshire, where they both died, Agnes in 1932 and Ruth in 1949.

the children

When their parents were convicted in 1889, Agnes’ four children –

George Grove (10)

Agnes Lilly (7)

John Thomas (6)

Mary Elizabeth (5)

– became pauper inmates at the Pauper Educational Establishment at Anerley Road, Upper Norwood, a district school intended for the education of pauper children to make them employable citizens.

Besides attending classes in subjects such as the Bible, tables, geography, writing, arithmetic and dictation, boys were taught trades such as tailoring, shoemaking, farming, or blacksmithing. Girls had three days of schooling a week and were taught household occupations such as baking, cooking, cleaning, ironing, mangling and needlework so that they could enter domestic service.

Charles Dickens described the establishment as:

a factory for making harmless, if not useful subjects, of the very worst of human material … leading a pitiable section of the great two-million-strong family of London from the road to crime into that of honest industry and self-respect.

George Grove Dale went on to become an orchestral musician playing the cornet. He worked in different theatres and in 1921 was employed as a musician at Bournemouth Winter Gardens.

He had two marriages, the first to Florence Mary Hoar in 1902 which ended in divorce in 1904. George then married Beatrice Eliza Jacolette in 1905, the daughter of Martin Jacolette, a well documented studio photographer with studios in Dover and South Kensington in London.

Martin Jacolette’s studio in South Kensington was at Queens Gate Hall on Harrington Road, a venue for theatrical productions and musical concerts and most possibly the place where his daughter met George Grove Dale.

relationship to me

Thomas Grove was the brother of my 3x great grandfather, Joseph Groves, on my maternal side. His daughter, Agnes, was thus a cousin of my great great grandfather, William Groves, and my 4th cousin.