Mending Them

Henry Cushing, a well documented American pioneer in brain surgery and a major in the U.S. Medical Corps attached to the British Expeditionary Force in World War 1, served at 46 Casualty Clearing Station at Mendinghem during the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele) in 1917.

He kept a diary of his wartime experiences which was later published in a book entitled A Surgeon’s Journal. In the entry made on Monday 27 August he recorded that

between July 23rd and August 23rd, 17,299 cases were evacuated from these three Mendinghem hospitals.

The three Mendinghem hospitals he referred to were Nos. 46, 64 and 12 Casualty Clearing Stations.

My grandfather’s sister, Florence Maud Williams, worked as a Staff Nurse for Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve at 64 Casualty Clearing Station in the period 2 August 1917 to 15 March 1918 alongside 46 Casualty Clearing Station where Harvey Cushing was recording day to day life at Mendinghem. Maud therefore nursed a proportion of the staggering number of 17,299 cases that Cushing noted were evacuated from Mendinghem in the first month of the battle.

A Casualty Clearing Station was as close to the front line that a British nurse served in World War 1 and was part of the chain of medical services that processed a wounded soldier from the front line. The first medical treatment was at a regimental aid post near the front line and then at dressing station from where a casualty could be sent back to the front or on foot, horse drawn transport, motorised transport or railway to a Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) some miles behind the front line. A soldier would either remain at a CCS if unfit for travel or returned to his unit or evacuated to a Base Hospital in France and then onto a home hospital.

CCS were often grouped near railway lines in clusters, such as the cluster of CCS 46, 64 and 12 at Mendinghem, so that they could work in rotation. Harvey Cushing noted that 46 and 12 were placed side by side and 64 across a railway track with the cemetery on the other side of 64. On 24 July, the 5th Army issued instructions that 46, 64 and 12 were responsible for lachrymatory (tear) gas cases, head cases (hence the appointment of Harvey Cushing), sick from the back area, walking wounded carried by vehicles other than motor ambulances and lying sick from the forward area.

The site for 64 CCS was marked out on 6 June and erected between 18 and 25 June in preparation for the battle that opened on 31 July. No 64 assisted at Cushing’s 46 until the first nursing staff arrived and opened to patients on 26 June. King George VI inspected 64 CCS on 6 July and

expressed great pleasure at the arrangements.

Visiting 64 together with its CO, Colonel Wolstenholme of the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC), Cushing recorded that 64 CCS was

wholly in tents … No. 64 represents the plan for all future CCS’s – tents to be lined up in columns of four … so that anyone can readily find his way when transferred from one CCS to another. The place is laid out in a rectangle with a broad central duckboard avenue, and A lines to the right for lying cases and B lines to the left for walkers, who should be able to find their own way.

Maud would have been specifically selected for her period of service at 64 CCS as a fully trained nurse who had served in a home hospital and stationary hospitals in France. This selection would have been based on confidential reports and for a fixed length of duty period of 6 months. She actually served 7½ months.

Mendinghem is not a town that can be found on any modern map as it was a fabricated name given to the CCS by the aptly named Colonel Chopping of the Royal Army Medical Corps and one of three names for a group of 5th Army CCS located in the same area of Belgium. With a touch of irony, these were named Mendinghem, Dozinghem, and Bandaghem – Mending Them, Dosing Them and Bandage Them. Cushing claimed that the army had also played with the discarded names of Endinghem, Kuringhem and Choppinghem (after Colonel Chopping).

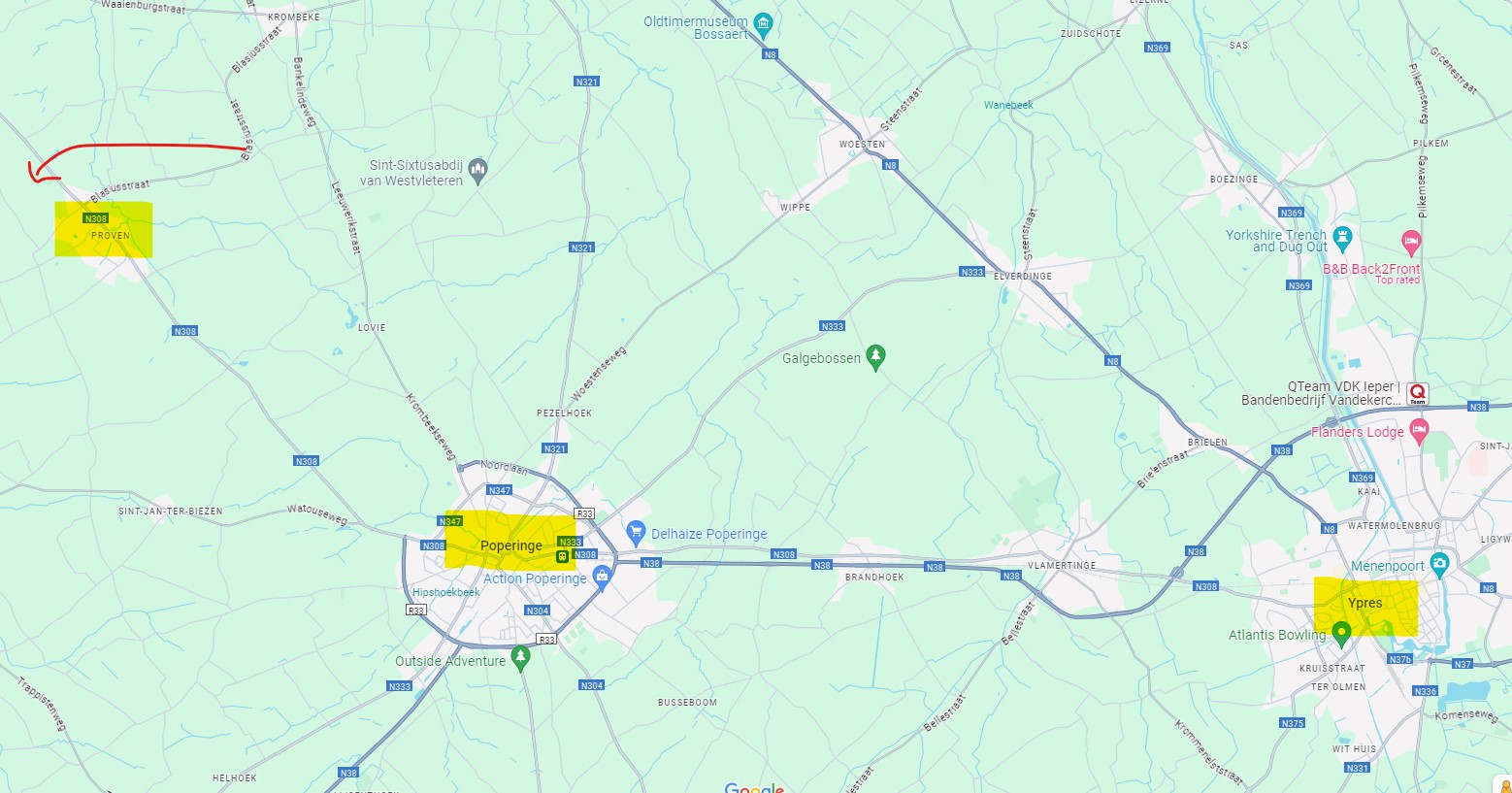

Looking at a map of Belgium today, Ypres is situated in the north west of the country with the town of Poperinge further to the west. The road that leads to the motorway to Dunkirk to the north east of Poperinge goes through the small Belgium town of Proven and Mendinghem cemetery (red arrow) lies back from the road about one kilometre north of Proven. It is literally in a Flanders field.

Mud, Bombs & Gas

Cushing’s account gives a unique insight into Maud’s experience at Mendinghem. The overall impression is one of rain and mud, uncomfortable living and working conditions with constant noise and threat of bombardment and exhausting long hours processing hundreds of casualties, horrific injuries and unfamiliar medical conditions.

The weather was fine in the last week of July but it began to pour with rain as the battle began on 31 July. Cushing then realised that Mendinghem had disadvantages

Pitch black, pouring rain … your electric torch burned out – trying to stick to slippery duckboards about a foot wide. Depressing for a well man, but imagine what these poor wounded devils have had to go through today, and what the many not yet found are enduring. The preoperative hut is still packed with untouched cases, so caked in wet mud that it’s a task even to strip them and find out what they’ve got.

On the next day, 2 August, Maud arrived at Mendinghem and Cushing observed that it was

Pouring cats and dogs all day – also pouring cold and shivering wounded, covered with mud and blood. Some … when the mud is scraped off, prove to be trifles – others of unsuspected gravity. The news, too, is very bad. The greatest battle of history is floundering up to its middle in a morass, and the guns have sunk even deeper than that. Gott mit uns was certainly true for the enemy this time.

Four days later stretcher bearers were carrying wounded soldiers between 46 and 64 CCS across mud was three or four inches deep –

enough to suck off your rubber boots.

Due to bombing raids, 64 CCS quickly lowered the floors of tents and provided dugouts for the nursing staff. Ditches were dug in the cemetery and used for refuge during bombing raids. Cushing gave a number of descriptions of the noise and bombardment. On 28 September he wrote

It was a little hard “sticking” tonight for it sounded as though the world were exploding – almost noisy enough for a field ambulance. At one time a munition dump went off near by – at another a Fritz came over, was caught and held in the searchlights for three minutes by the watch and in the midst of Archie flashes one could see his tracer bullets as he methodically swept the road with his machine gun. Soon a lot of bombs were dropped near by – Proven perhaps – and every now and then the big French naval guns would go off and rattle the operating hut as though they were next door instead of a mile or so away.

On 1 October he observed that

The bombardment, though six miles away was so heavy that the operating room shook with it … this was practically continuous from the time I awoke till about noon.

Cushing mentioned that one major cranial operation had been a day’s work in peace time. During the Third Battle of Ypres, he regularly carried out 8 such operations per day and at one point 12. He often had to resort to operating by candle light when the lights were switched off during bombing raids and complained about a shortage of boiling water. Observers frequently came from 64 to watch this pioneering surgeon at work. Maud maybe had opportunity to be among these observers.

Besides gunshot wounds, infections, wounds infested with maggots and other wartime injuries, an overriding problem was gas. The Germans first used mustard gas on the western front on 12 July and the allied medical staff at Mendinghem clearly had to come to terms with its effects which included a brown oily liquid that produced a horseradish or garlic like smell, terrible blistering, bronchial problems and internal gas infections often as a result of a gas infected bullet or shrapnel entering the body. Medical staff observed that the gas had a tendency to seep through uniforms but not straps or pockets that contained pocket books or Bibles. Nurses, doctors and orderlies got sick themselves from handling the soldiers and their clothing. 46 CCS took in 1000 mustard gas casualties with 20 fatalities on 22 July alone.

To quote Cushing again

Their eyes bandaged, led along by a man with a string while they keep to the duckboards. Some of the after-effects are as extraordinary as they are horrible.

On 26 November, No 64 Casualty Clearing Station was allocated as ‘Special Hospital’ for ‘N.Y.D. (not yet diagnosed) Gassed’ cases and Maud must have nursed many soldiers suffering from the effects of gas.

64 CCS was transferred to the Fourth Army on 20 December and to the Second Army on 13 March 1918. Shortly afterwards on 15 March, Staff Nurse F M Williams QAIMNSER proceeded to England and was ‘struck off the strength’ at 64 CCS. An order was received from the Director of Medical Services Second Army to close the hospital immediately on 26 April and to proceed to a new site at Watten in France. 64 CCS’s dramatic ten month life at Mendinghem was at a close leaving behind a cemetery that is the visible memorial at Mendinghem today.

The Road to 64 CCS

Maud was born at 91 Lichfield Road in Wednesfield (north east of Wolverhampton) on 15 September 1886 as one of my great grandfather’s nineteen children. Her nursing training as a probationer nurse at the Union Infirmary, then part of the recently built Wolverhampton Union Workhouse (now New Cross Hospital in Wednesfield), began on 16 March 1909 at the age of 22. Maud left Wednesfield as a staff nurse in 1913 and went onto work as a sister in charge of the male medical wards at Cardiff Union Hospital on the site of the Cardiff Union Workhouse until April 1915. From there she went on to work for a short time at the Infirmary at Selly Oak in Birmingham.

On 15 June 1915, ten months after the outbreak of war whilst at Selly Oak, Maud made an application to join Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve , a reserve service for Queen Alexandra’s Military Nursing Service established in 1908 but expanded during the period of World War 1. QAIMNS has very exacting recruiting standards maintained by the Reserve service. Applicants had to:

- be a British subject aged between 25 to 35

- be single or widowed

- have a good social standing

- have undergone 3 years’ training in a hospital approved by the QAIMNS nursing board

- give two references – ‘one being a lady, not a member of your own family’.

At the time of her application, Maud was 28 and single. Her father, Thomas Williams, was a master tailor working on his own account who owned a moderate amount of property in Wednesfield. Clearly, Maud’s social background met QAIMNS’s stringent requirements and she qualified as the daughter of a ‘professional man’. It can also be concluded that the Union Infirmary at New Cross in Wednesfield must have been on the list of approved hospitals for nursing training. As for references, Maud gave the names of matrons at both Wolverhampton and Cardiff. Her experience in the male medical ward at Cardiff could also have been an attractive aspect of her application. Maud signed a first yearly contract with QAIMNSR on 14 July 1915.

Maud did not go to France in the first instance as even trained nurses had to demonstrate their capabilities at a home hospital before being considered for overseas service. So, her first year of military service was at Lichfield Military Hospital so that she eventually embarked for overseas service on 28 June 1916. She nursed firstly at No 1 Stationary Hospital and then No 3 Stationary Hospital both of which were located at the race course in Rouen, France. Stationary Hospitals were a type of Base Hospital much further back from the front line than a CCS.

Mentioned in Despatches & Promotion

Shortly before travelling to 64 CCS Maud was granted a two week period of leave. After another similar period of leave in March 1918 after Mendinghem, Maud was assigned to 32 Stationary Hospital in Wimereux on the north coast of France east of Calais where she was stationed for just over a year until demobilisation on 6 April 1919.

32 Stationary Hospital was located at the Grand Hotel du Golf et Cosmopolite which lay directly on the coast facing the English channel behind which a golf club still exists. The Hotel was a large three storey building with a fourth storey built under the roof which had accommodated more than 100 guests before the war. After the outbreak of war, the hotel became the Australian Voluntary Hospital in October 1914, No. 3 Australian General Hospital in June 1916 and eventually in the same year No. 32 (British) Stationary Hospital.

The very exposed position of the hospital virtually on the shore facing the English Channel meant that the nurses lived in cold and windy conditions. The first Australian nurses had accommodation in bell tents in front of the hotel which must have been extremely cold and uncomfortable at times. A house was eventually requisitioned as a nurses’ home but the walls very thin and the accommodation could still be very cold. It took fifteen minutes to walk to the hospital and nurses reported that it was a ‘rather trying walk’ with it difficult to stand against the gales and winds.

Maud’s Matron at Wimereux was Jessie Hume Congleton, reportedly a strong character, who had been appointed to QAIMNS since 1906. She had shown considerable bravery and had been awarded the Royal Red Cross First Class and mentioned in Army Orders ‘for conspicuous bravery during a fire at No. 14 Stationary Hospital’. Maud followed in her footsteps as Staff Nurse F M Williams was mentioned in despatches recorded in a supplementary to the London Gazette on 25 May 1918.

QUEEN ALEXANDRA’S IMPERIAL MILITARY NURSING SERVICE (RESERVE)

Barnfield, A./Sister Miss I. E.

Brizzell, A./Sister Miss A. I. J.

Brown, Staff Nurse Miss M. C.

Charter, A./Sister Miss S. M.

Cheal, A./Sister Miss H. E.

Fuller, A./Sister Miss E. E.

Holmes, Staff Nurse Miss G.

Horsley, A./Sister-in-Charge Miss S.

Littlejohn, Staff Nurse Miss C.

Pattison, A./Sister Mrs. J. M.

Scott, Staff Nurse Miss E. R.

Shann, Staff Nurse Miss C. L.

Stock, Staff Nurse Miss L. A.

Trenchard, Staff Nurse Miss E. S.

Wade, A./Sister Miss S. A. W.

Webb, A./Sister Miss M.

Wilkinson, A./Sister Miss A. M.

Williams, Staff Nurse Miss E. A.

Williams, Staff Nurse Miss F. M.

Williamson, A./Sister Miss J. M.

It is not known exactly why Maud was mentioned in despatches as this is not recorded in her service record, the war diary for 32 Stationary Hospital or reported in local newspapers.

Her Victory Medal has the emblem of oak leaves in bronze that was issued for a Mention in Despatches for an act of bravery.

Records of other nurses indicate that they received the same honour for such acts as:

- distinguished service

- devotion to duty

- great coolness

- gallantry during an enemy air raid / shelling / fire / bombardment

- disregard of danger

- continuing to attend to the wounded during heavy bombardment

- good work.

Maud was promoted from Staff Nurse to Acting Sister at some time between 25 May 1918 and April 1919, maybe as a result of being mentioned in despatches.

After the armistice in November 1918, Maud was assigned to ambulance transport service, probably an ambulance train, to England with a following 14 days leave around Christmas. Her service at 32 Stationary Hospital ceased on 4 April 1919. She arrived at Folkestone the next day, stayed overnight at the Nurses’ Dispersal Hostel and then returned to her home address in Wednesfield. Maud’s war was over.

Relationship to me:

Florence Maud Williams – paternal grandfather’s half sister

Albert Theodore Williams – paternal grandfather

Thomas Williams – great grandfather