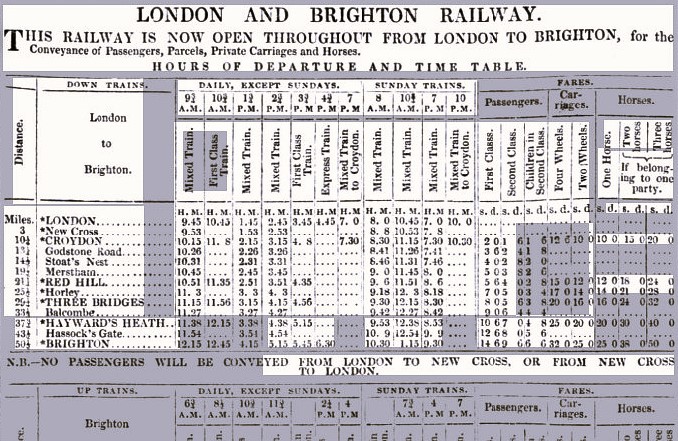

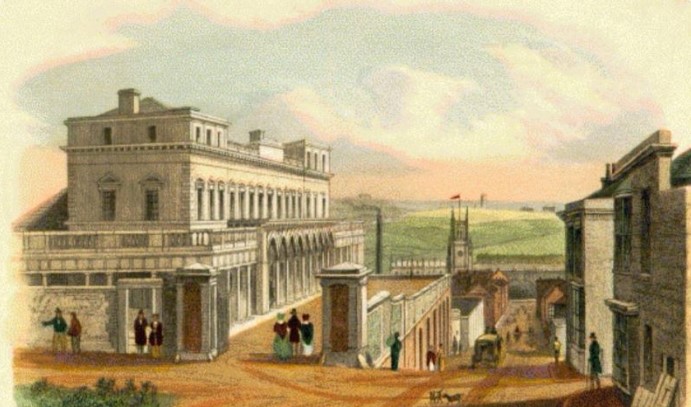

Tuesday 21 September 1841 marked the day that the London to Brighton railway line officially opened. A milestone for transport and travel, the railway was a catalyst for economic expansion and social transformation as new opportunities reshaped the seaside town of Brighton.

Trains could reach Brighton quickly at affordable prices and the town developed to cater to rising numbers of travellers and day trippers. The town’s population swelled, creating a growing demand for housing and infrastructure. Many businesses benefitted from this influx of visitors.

The railway also created many jobs sparking a surge in employment opportunities. The London Brighton & South Coast Company established a large locomotive works near the train station in 1854 and became a major employer in the town. Streets developed to the east of the station and the workforce expanded.

A Railway Labourer

My great great great grandfather, William Turner, joined the ranks of this workforce. The son of an agricultural labourer, William was born in West Grinstead in 1812. In 1836, he married Mary Huggett, the daughter of the miller at Copperas Gap, Portslade.

The couple had four children. Mary Ann was baptised in Portslade in February 1837, Willliam in Portslade in July 1838, Richard in Brighton in February 1840 and Henry in Portslade in September 1841.

William (snr) was recorded as living at Red Cross Street close to the railway terminal in Brighton when his son Richard was baptised in 1840. The family appeared again in Copperas Gap on the census taken in June 1841.

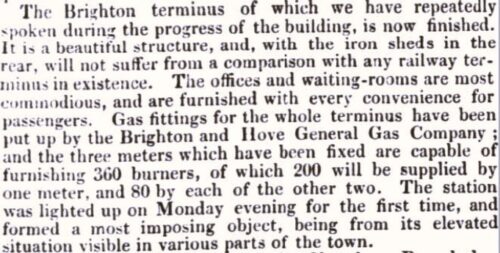

William was a labourer and must have sought work in Brighton during some period between the middle of 1837 and 1841. This was possibly some kind of work involving the building of the railway line and Brighton railway terminus. Later newspaper reports in 1855 did state that William had been in service for the railway company for many years.

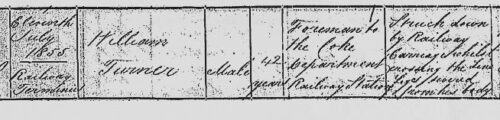

By 1851, William and his family had moved back to Brighton to live at Claremont Place. The census of that year records he was a bricklayer labourer but by 1855 he had risen to the position of foreman of the coke department.

A Tragic Turn

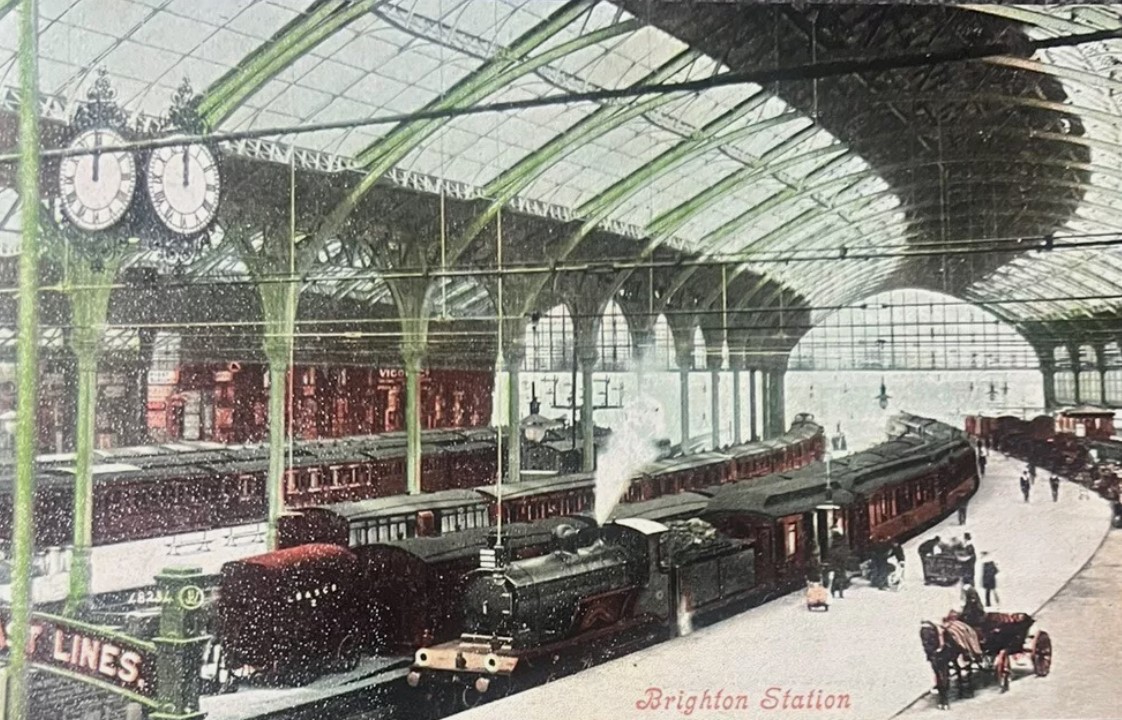

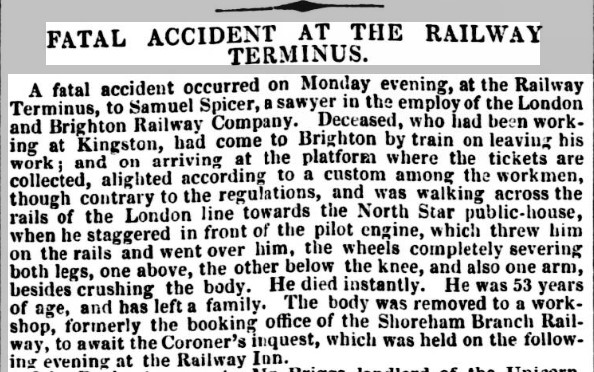

William’s story took a tragic turn on 11 July 1855. On that day at about ten minutes past one, William went down the platform for the train to Shoreham and crossed the railway lines diagonally to get to the London train platform and the coke sheds. It was pouring with rain so that William had opened his umbrella which he carried over his head in front of him to shield himself from the rain.

The train for London was due to leave at a quarter to two and was being prepared for this departure. An engine was shunting empty passenger cars back into position. As he crossed the line, William failed to hear or see the approaching train despite whistles and warning shouts from railway porters.

Then the carriage buffers hit William in the chest. He fell onto his back with his legs across the metal rails and was dragged for about twelve yards. The wheels of five or six carriages ran across his thighs almost severing his legs from his badly injured body.

One of the porters, William Bonney, ran over and had to get the engine driver to move the train as the wheels were still on William’s body. Bonney got a stretcher and William was quickly taken to and placed in a van.

Bleeding profusely, he was in deep shock gasping for breath. A policeman, George Brown, who knew William and had often spoken to him on his way to and from work said that William was not “sensible” and did not have understanding of the situation.

William died four or five minutes after reaching the van and a surgeon, Mr Verrall, arrived only in time to see William take his last breaths. He was 42 years old.

The Inquest

An inquest into William’s death was held that same evening at the Railway Inn on Surrey Street.

Henry Anscomb of the railway police testified that it was against the company rules to cross the rails at the point where William was run over. The workmen had to use an entrance on the east side of the station which involved taking a longer way that avoided the railway lines.

A board outlining the rules and regulations was brought from the railway terminus and it was shown that the rules for the east side entrance applied only to the workmen. It did not apply to the foremen who were allowed to come and go by the front entrance.

Nevertheless, the jury returned a verdict of “Accidental Death” and the coroner remarked that William had met his death by misadventure. No blame whatever was assigned to the London Brighton & South Coast Company. It is likely that William’s widow and family did not receive any compensation for their tragic loss.

relationship to me

My 3x great grandfather, William Turner (born West Grinstead 1812, died Brighton railway terminus 1855), was the great grandfather of my paternal grandmother, Grace Dorothy Turner.