My grandparents moved to Dennis Hall Road in Amblecote after houses were first constructed on the land known as Dennis or Dennis Park at the outbreak of World War II.

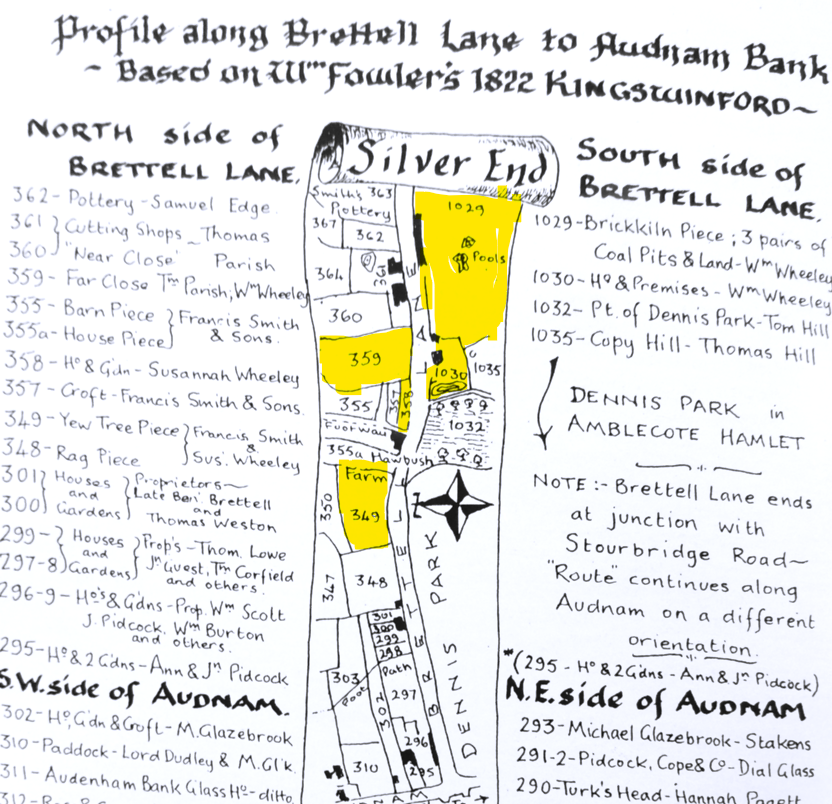

Driving or taking the bus to my grandparents’ home through Brierley Hill, down Church Street past the war monument at St. Michael’s Church, then crossing into Brettell Lane at Silver End is a journey that is deeply imprinted on my mind’s eye.

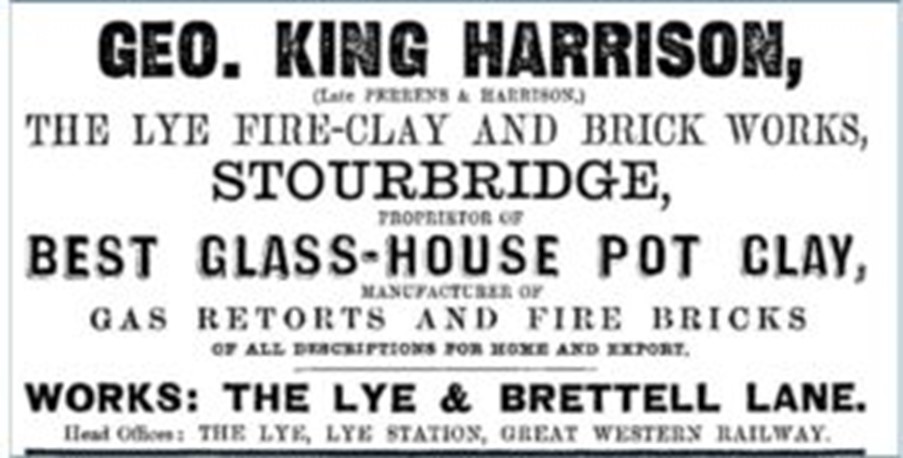

So is the image of a long wall that ran along Brettell Lane shortly before the turning into Dennis Hall Road, painted with the name George King Harrison in large letters.

The name, George King Harrison, resonated with me simply since I saw it so often and because of its semblance to the famous name of George Harrison in the Beatles.

My memory is that opencast mining took place in the expanse of land behind the wall lying between Stourbridge Canal, Brettell Lane and the back of the houses that ran down Dennis Hall Road, a fact verified by this article from the Birmingham Daily Post in 1969:

A housing estate sprang up in the 1990s and the wall along Brettell Lane disappeared. Indeed, the section of Brettell Lane between Dennis Hall Road and Silver End now appears somewhat nondescript. Closer examination though reveals that this small pocket of the Black Country was a transportation hub with interconnecting road, waterway and railway links and once a very significant centre of industry.

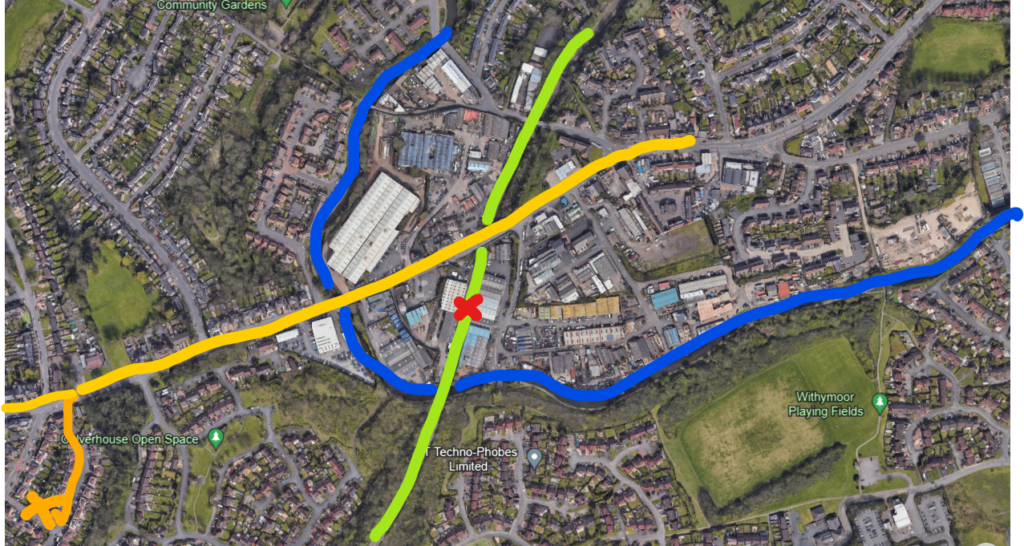

Brettell Lane itself was a main thoroughfare with a tramway providing connections to Stourbridge to the south and Brierley Hill and Dudley to the north.

Stourbridge Canal, completed in 1779, winds from the Nine Locks at the Delph forming a loop running under Brettell Lane and back towards Brierley Hill.

Brettell Lane railway station opened on the line between Worcester and Wolverhampton in 1852, was mostly used for goods and freight after the 1880s and closed in 1962.

The Best Clay

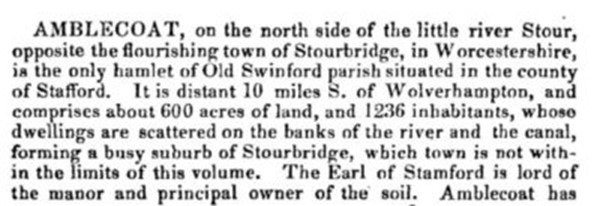

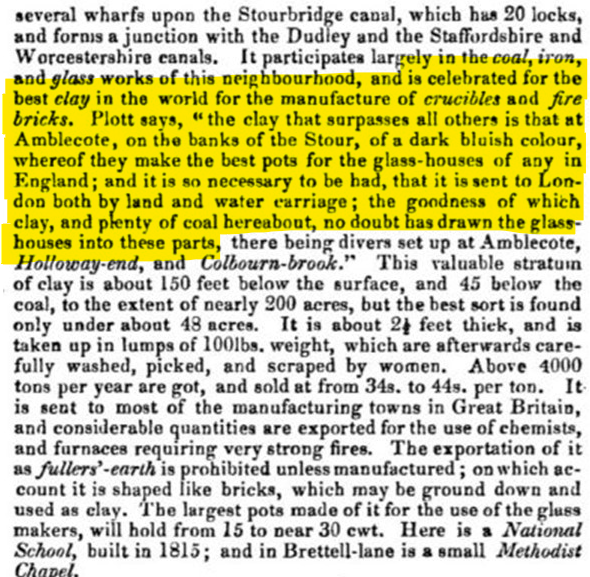

In “The Natural History of Staffordshire” in 1686, Robert Plot wrote that Amblecote had by far the most preferable clay, adding that the best pots for manufacturing glass were made from Amblecote clay and noting the number of glass houses in the area. This entry for Amblecote in the “History, Gazetter & Directory of Staffordshire” in 1834 refers to Plot:

Home to high quality deposits of fireclay, Brettell Lane subsequently became a centre of maybe the most essential industry of the Industrial Revolution, the manufacture and trade of firebricks, technically refractories.

A refractory is a shaped article made of certain clays and minerals that can withstand variations in temperature for long periods of time without distorting or cracking. The Black Country led the world in the manufacture of refractories and John Cooksey, author of “Brickyards of the Black Country, A Forgotten Industry”, claimed that firebricks were the most important industry in the world:

“It is worth considering that without refractories no other industry could have existed. Somewhere along the manufacturing process of every product refractories would be involved, …The refractories industry shaped the way the Industrial Revolution progressed, from bloomeries to iron and steel works, from Cylinder Glass to Pilkington’s float glass furnaces, from the Rocket to the main line steam locomotives, from disease to Henry Doulton’s salt glazed earthenware pipes, from oil lamps to William Murdoch’s gas from coal experiments, and so it goes on.”

Firebricks

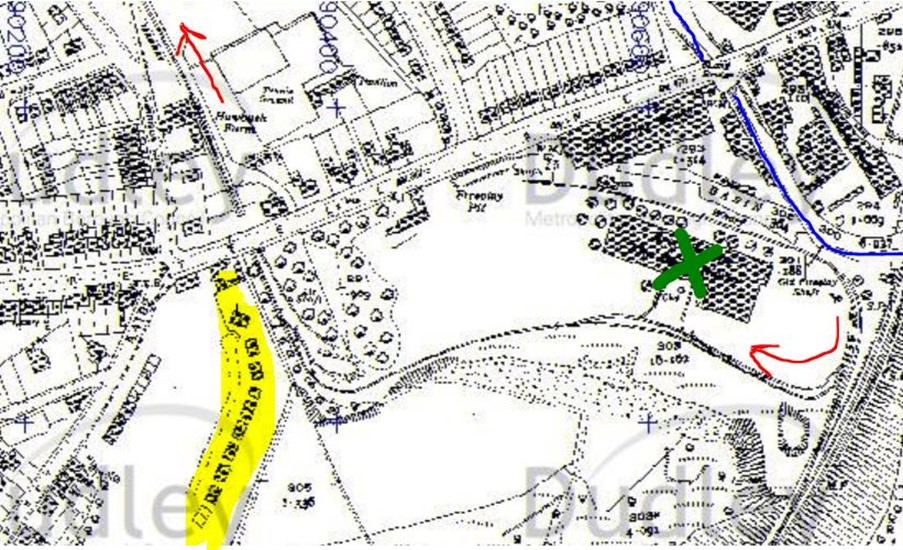

Firebrick manufacturing and fireclay mines dotted the area. Clay was found between coal seams and both clay and coal were frequently worked from the same shaft.

George King Harrison

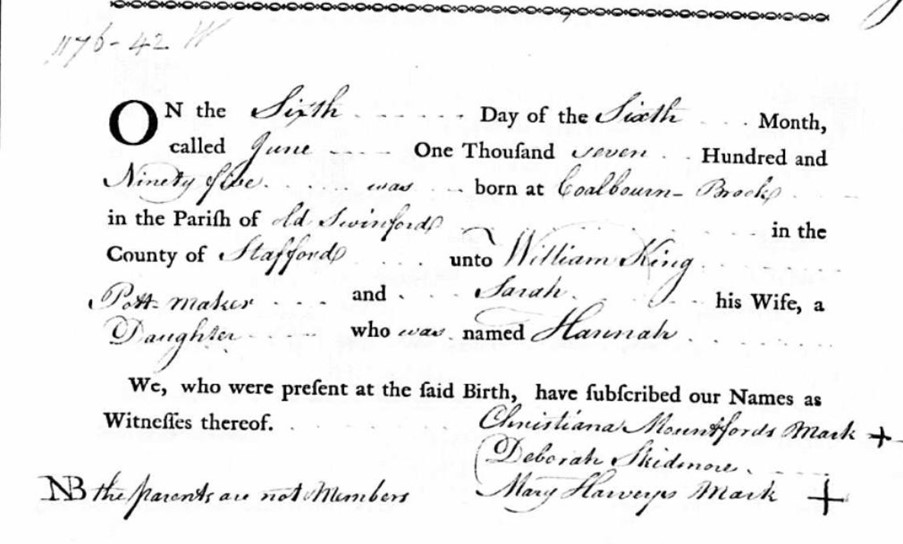

G. K. Harrison was a major player in this firebrick trade. He was born at Toxteth Park in Liverpool on 4 June 1826, the eldest child of Quakers, Benjamin Harrison, a corn merchant, and Hannah King, the daughter of William King, a pot maker and clay merchant, of Coalbourn Brook in Amblecote.

Hannah returned to Amblecote from Liverpool at some point after the death of her husband at the age of 42 in 1834 and was living on independent means in Amblecote by the time of the 1841 census.

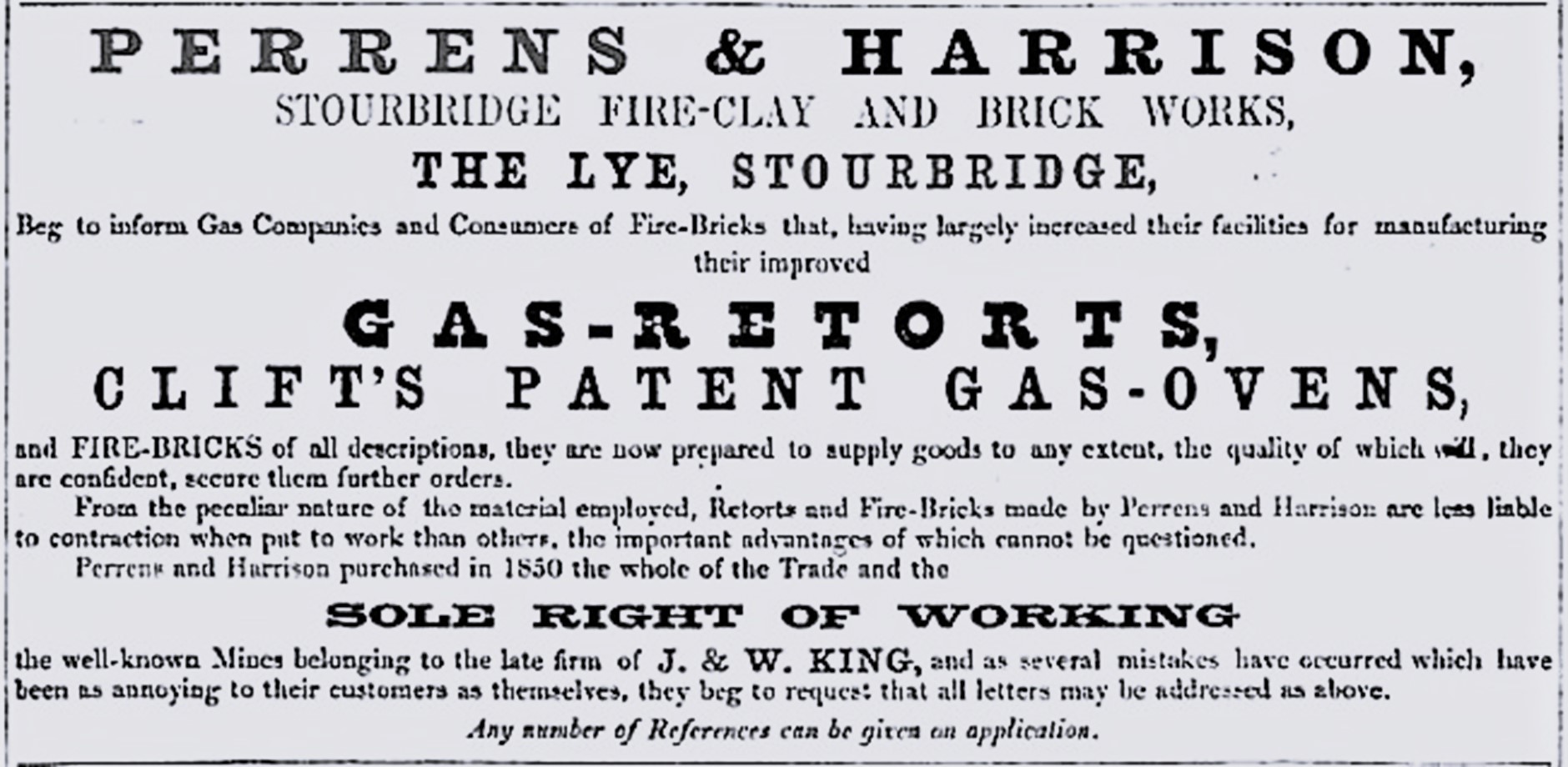

By 1851, the family resided at Coalbourn Hill, now the site of the Ruskin Glass Centre. George King Harrison was then 24 and a clay merchant, having gone into partnership with his cousin, William King Perrens, a year previously and taking over the business of Joseph and William King in Lye (Stourbridge), possibly owned by Hannah Harrison’s brothers.

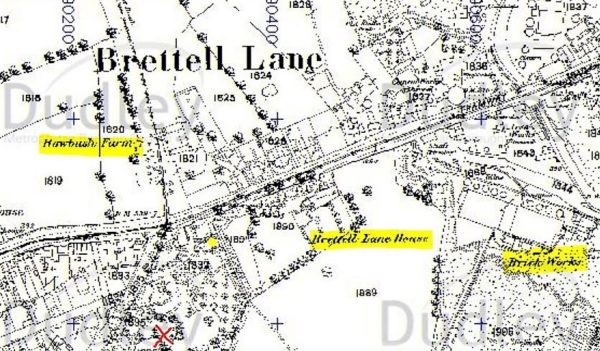

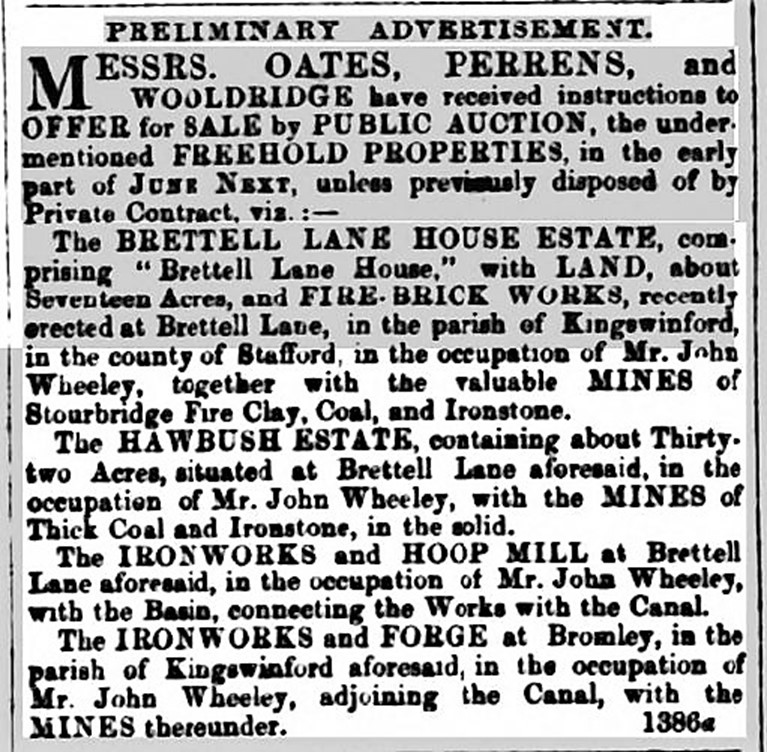

In 1866, the partners purchased the Brettell Lane House Estate including 17 acres of land and a firebricks works owned by John Wheeley, the son of Thomas Wheeley, a glass manufacturer, and Susannah Seager. The Wheeleys owned considerable land and mines in Amblecote and the surrounding area.

John’s brother, William Seager Wheeley, was a noteworthy name in the glass manufacturing trade and Wheeley’s Brettell Lane Glasshouse had been situated on the opposite bank of the Stourbridge Canal to the firebrick company. Waterford Crystal attributes improvements to its glass making after the installation of the Wheeley furnace built by William in 1830. William died in 1859 and John Wheeley and Co, iron master and clay manufacturer, went bankrupt in 1868 so that the significance of the Wheeley name in Amblecote declined.

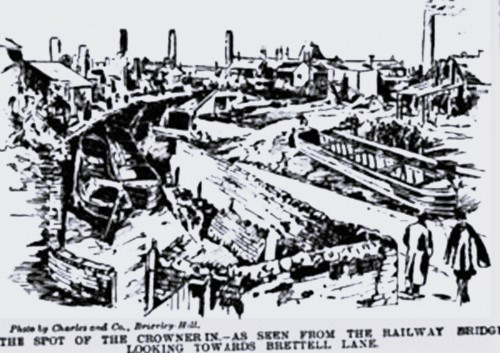

Nevertheless, when the Stourbridge Canal burst at the basin at G.K. Harrison’s fireclay and brickworks in 1903, it was still known as Wheeley’s basin.

William King Perrens retired in 1875 leaving his cousin as the sole owner of the George King Harrison company.

On his death in 1906, George King Harrison’s effects were valued at over £112,000, a vast sum of money worth many millions of pounds today.

The County Advertiser reported:

He was, however, destined for a position in connection with one of the most famous industries of the neighbourhood, namely, the fire brick trade; and in due course he entered into partnership with his cousin, Mr. William King Perrens, and with him carried on works which had previously belonged to Messrs. Joseph and William King, at Lye. These were greatly extended from time to time, and for a period the firm had similar works at Cradley, and at Wilnecote, in Warwickshire, where they also owned collieries. The firm of Perrens and Harrison prospered greatly, and became famous for the quality of their goods and the straightforward character of all their business transactions.

In 1866 the firm bought the small fire brick works carried on at Brettell Line by Mr. John Wheeley, and shortly afterwards, on the failure of Mr. Wheeley – Hawbush estate.

In 1875 Mr. Perrens retired from the firm, and the whole of the extensive works came into Mr. Harrison’s hands.

The purchase of Hawbush, and of Nagersfield subsequently, brought about a great change in Brettell Lane. The fine deposit of fireclay under the first named was worked, and the firebrick works erected on their present site were considered the model works of the neighbourhood. The pits under the estate were developed by Mr. Harrison, and the extensive firebrick works at Brettell Lane were laid out on the most modern principles.

In due course the pits at Nagersfield were re-opened, and a plant put down of the most efficient description for the working of the minerals and the conversion of the clay into bricks. At the same time a railway from the pits at Nagersfield to the works at Brettell Lane was constructed and worked by electric traction. These extensive industrial operations gave much employment in the district, and added not a little to its prosperity. With advancing years Mr. Harrison naturally felt the management of his large works and the control of the great business which they involved an increasingly heavy responsibility; and so some two years ago his concerns were turned into a limited company.

Edward Bowen

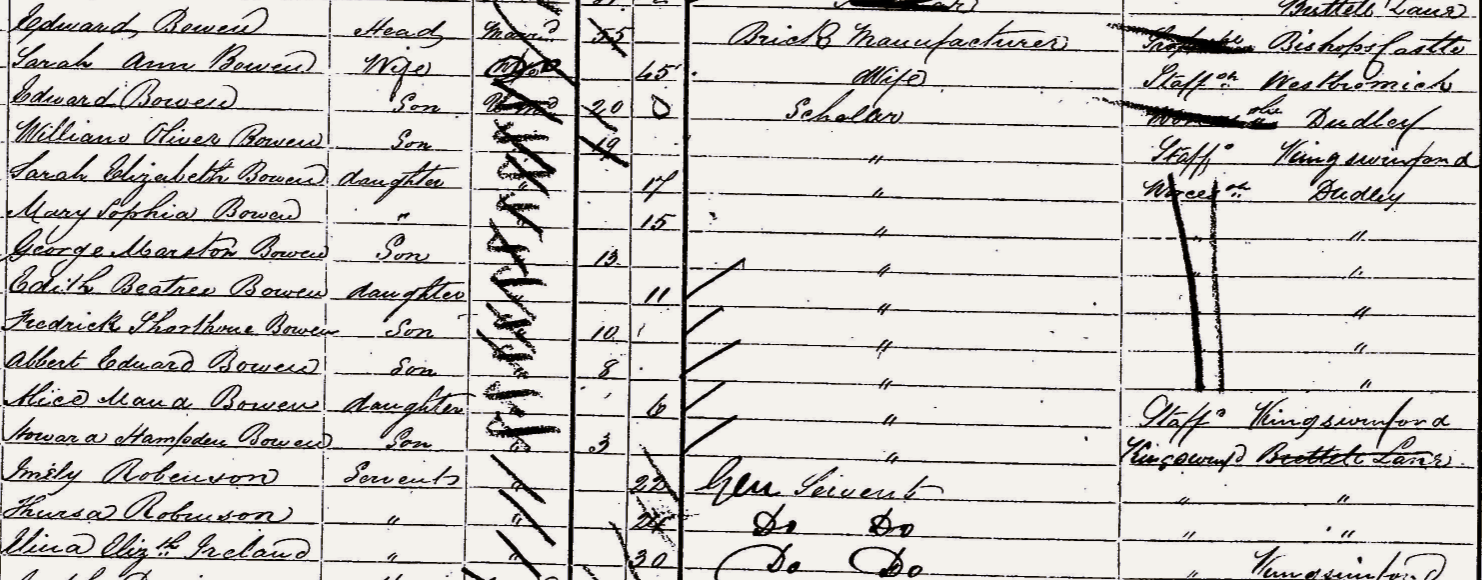

The Clattershall Fireclay and Brick Company lay further along the canal towards the Nine Locks and Brierley Hill, beyond the railway bridge that crosses the canal.

The company’s coal and clay mine were owned by the Earl of Dudley and run by Burford & Co until about 1865. Edward Bowen then took over the business and he and his family moved to Brettell Lane from Dudley, where Edward had previously run a drapery business on the High Street.

Edward Bowen died in 1884 and the business became a limited company, operating as Bowens Limited from 1889. The name Bowen survives today with Bowen’s Bridge spanning the Stourbridge Canal at the former location of the Clattershall works.

Harris and Pearson

A further outstanding reminder of the firebricks trade stands on the opposite side of Brettell Lane. Originally built using company bricks made from local fireclay in 1888, the former Harris and Pearson office is now a beautifully restored grade II listed building.

The Harris and Pearson works originally stretched across a site bounded by the Stourbridge Canal as it loops back towards Bull Street and Brierley Hill, Bull Street itself, the railway and Brettell Lane.

Due to the restoration in 2004 and 2005, Harris and Pearson is well documented.

Churches

Some unique churches in the Black Country also reflect the significance of the firebricks trade to the area.

The Holy Trinity Church in Amblecote was completed using firebricks donated by Joseph and William King in 1842.

Bricks for Christ Church in Quarry Bank, built in 1844, were supplied by George King Harrison.

St. John’s in Brockmoor was built in 1844/45 using firebricks and blue brindle bricks from Webb, Harper and Moores whose company was on the Delph, to the east of Silver End.

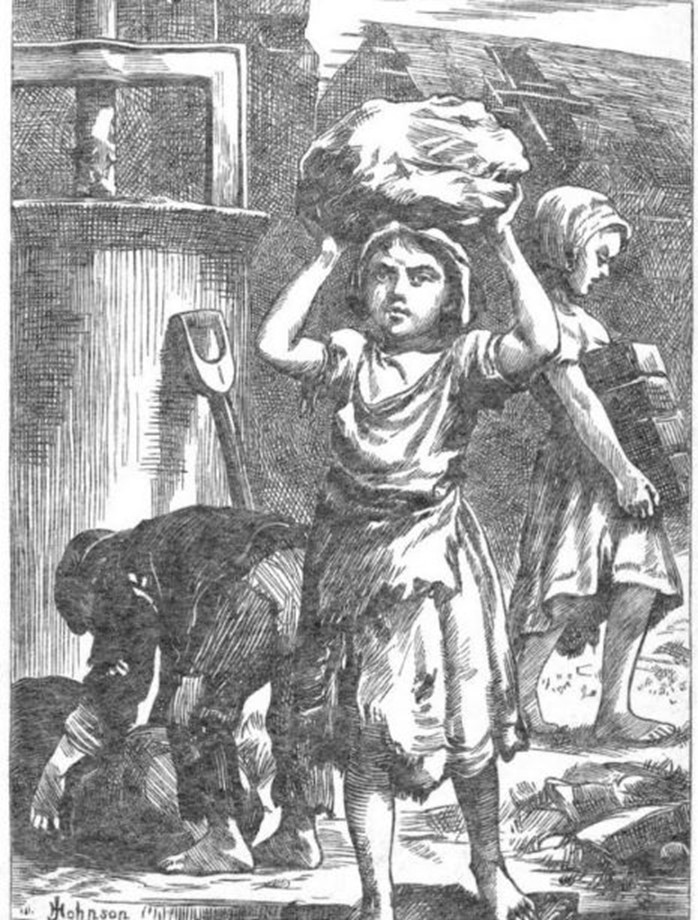

Child Labourers in the Brickyards

The report of the Inspectors of Factories in 1864 recorded that particularly very few men worked in the firebrick trade in South Staffordshire as men were in demand for other industries such as ironworking. Elihu Burritt published “Walks in the Black Country and its Green Borderland” in 1868 and noted that 75% of the labourers working in Black Country brickyards were female with two thirds of these aged between 9 and 12.

Bricks were made by hand in a process where clay was carried to women working at a moulding bench. The moulder then threw and pressed the clay into moulds. The mould with the moist brick was then carried to a floor or drying ground.

Women moulders were aged between 20 and 30 on average and the clay and brick carriers, or “pages”, between 9 and 16. Some sources report children as young as four or five years of age working in brickyards. The moulders paid the carriers, the pages, directly.

My great great grandaunts, Fanny Eliza Skidmore and Susanna Skidmore, were two such child brickyard labourers. Both Fanny and Susanna were working as brickyard labourers by the time of the 1851 census when Fanny was 15 and Susannah 13. As they were 5 and 3 at the time of the previous census, it is difficult to know exactly the age at which they started this labour. Elihu Burritt’s description of a 13 year old clay carrier gives an impression of the sisters’ working lives:

“Another girl, a little older, brought the clay to the bench. …She was a girl apparently about 13. Washed and well clad, and with a little sportive life in her, she would have been almost pretty in face and form. But thought there was some colour in her cheeks, it was the fitting flush of exhaustion … She first took up a mass of the cold clay, weighing about twenty-five pounds, upon her head, and while balancing there, she squatted to a heap without bending her body, and took up a mass of equal weight with both hands against her stomach, and with the two burdens walked about a rod and deposited them on the moulding bench”.

Various sources discuss the weight that brickyard girls carried and the distances they walked. The figures are consistently staggering. The 1864 report from the Inspector of Factories stated that a child clay carrier carried somewhere between 20 to 40 pounds on her head and another 10 to 20 pounds in her arms, making around 250 journeys a day. A clay carrier could walk 14 miles a day including walking to and from work. An older clay carrier aged between 14 and 16 could carry 60 pounds of weight up to 300 times a day, walking 22 miles a day. Those who carried the bricks from the moulders carried around 10 pounds of clay and a mould weighing about 4 pounds about 2,000 times a day. The hours were long, quoted as being from 6 or 7 in the morning until 6 in the evening with work on Saturdays and Sundays.

Clearly, these labourers had very little or no schooling or education. Probably as many as 50% never went to school at all and it was reported that not one in ten of the women and children could read or write. Fanny Skidmore could certainly not write as she could not sign her names on documents and it was unlikely she or her sister could either read or write.

The 1864 report concluded,

“Yet these are in fact … the rising generation of the most civilized country of the world. Ignorant, untaught, an unheedful of education, they pass through life, … The schoolmaster is to them what a conjurer is to savages, a mysterious superior being.”

Observers also expressed consternation at the lack of femininity and morals in the brickyards:

The women are “undistinguishable from men, excepting by the occasional peeping out of an earring, sparsely clad, up to the bare knees in clay splashes and evidently without a vestige of womanly delicacy”. “All these things, the criminality, levity, coarse phrases, sinful oaths, lewd gestures and conduct of adults and youths, exercise a terrible influence for evil on the young children. Hence a generation full of evil phrases, manners and thoughts is daily growing up in our midst without the knowledge of better things. It is quite common for girls employed at brickyards to have illegitimate children.”

Robert Baker, Inspector of Factories 1864.

“The evil of the system of employing young girls at this work consists in its binding them from their infancy, as a general rule to the most degrading lot in after life. They become rough, foul-mouthed boys before nature has taught them that they are women. Clad in a few dirty rags, their bare legs exposed far above the knees, their hair and faces covered with mud, they learn to treat with all contempt all feeling of modesty and decency. During the dinner hour they may be seen lying about the yards asleep, or watching the boys bathing in some adjoining canal. While their work is over they dress themselves in better clothes and accompany men to the beer shops. The natural or even necessary results of a system like this on the character of the lower working class of the district can be easily inferred.”

Francis D. Longe, The Brickyards of South Staffordshire (1865?).

“A story told by a brickworks manager about a girl carrying clay who looked ill and he thought she was suffering from a previous nights drinking, saying to her yoe doe look up to much this morning, to which her reply was, neither would yoe if yoe’d had a babi in the night”.

Report of Factories Inspectors, 1875.

A Factories’ Act was passed in 1872, prohibiting employment of children under the age of 16 in brickyards although the report of the inspector of the Factories’ Act in 1873 commented:

“In firebrick making sheds, the law forbidding the employment of females under 16 years of age has certainly become a source of considerable annoyance to the employers, … After great consideration, the question I am inclined to think is that the reduction of the age of females in the firebrick sheds (but only in these) from 16 to 14 would be of an advantage to this trade which is a very important one.”

The industry was indeed booming. Demand was high with fierce competition for fireclay and products made from it. John Cooksey noted that there were over 30 brickyards making firebricks with an astonishing 258,792 tons of fireclay extracted in 1874 alone.

A Commission to look into the working of the Factories’ Act met at the Primitive Methodist schoolroom at Old Hill in 1875. The first witness was George King Harrison. He confirmed that firebricks continued to be made by hand exclusively by women as no machine for the manufacture of firebricks had been found. The women laboured indoors “in well warmed and ventilated places” working a 7 hour day.

Harrison argued that women had to learn brickmaking before the age of 16 and he applied to the Commissioners to allow girls to start working from the age of 14 or 15 as “no brick makers were coming on”. Firebricks had to be made “square and solid”. A “clod” had to be made and unless girls learnt this at a young age, they never learnt to make a good brick. In addition, Harrison claimed workers in his yard wished to work longer hours and on Saturdays as well as employ and instruct their children. Many women needed this work because of the “curse of drunkenness” amongst working men in the district.

Fanny & Susanna Skidmore

relationship to me:

Fanny Eliza Skidmore (1846-1894) great great grandaunt

Susanna Skidmore (1848-1875) great great grandaunt

sisters of William Henry Skidmore (1850-1911) my great great grandfather

Fanny Skidmore married Richard Williams, a coal miner, in 1866. She bore 11 children and died on 31 January 1894 at the age of 49 when her youngest child, Richard, was about 4. The causes of her death were aortic regurgitation, a valve disease where the valve allows blood to flow backwards into the heart, and cardiac failure. Richard Williams then married Ann Maria Bunce in 1896.

In October 1873, Susanna Skidmore married Henry Evans, an iron works labourer and blast furnaceman. She was then 25 years old and she died just over two years later on 28 November 1875. The causes of her death were thrombosis for 21 days and an abscess on the left lung. She did not have any children and Henry Evans married Martha Hill in 1880.

Interesting that the Inspector of Factories concluded in favour of the employers that it would be better if girls started this work at 14 rather than 16, rather than seeing the legislation as a step forward. Rights and protection are always hard won it seems.

There is another interesting aspect in the connection to non-conformism. George King Harrison came from a Quaker family. There is some evidence that Edward Bowen was an adherent of the Independent Chapel in Dudley. The Pearsons were strong Methodists. The inclination would be to believe that these industry owners would have tended to support reform and education rather than arguing the contrary.

The importance of non-conformism to the Black Country arises very often in research and is an area that warrants some detailed research in itself.

Thank you for your comment.