Industrialisation brought about a rapid growth in Dudley in the first half of the 19th century quadrupling the size of the population. Fields around the town quickly developed into dense huddles of streets and courts with housing, factories, workshops, pubs and shops packed together with little or no planning.

Hundreds died in the town during an outbreak of cholera in 1832, many children died of malignant scarlet fever a year later and epidemic typhus or ‘Irish fever’ struck in 1847. Two years later in 1849, Asiatic cholera, spread by contaminated food and water, hit Dudley again killing somewhere between 500 and 600 people.

Francis Jeavons and Mary Ann Shaw were born and grew up in Dudley during this period and were both 18 years old at the time of their marriage in Dudley in 1838. Mary Ann was pregnant with their first child, Hannah, born on 6 December later that year. Over the course of the next 20 years, 13 known children were born to the marriage.

| relationship to me | |

| Florence Groves – great grandmother | |

| Mary Ann Jeavons (Groves) – great great grandmother William Jeavons – great great great grandfather | |

| Francis Jeavons – brother of William Jeavons, 3rd great granduncle |

The Barracks

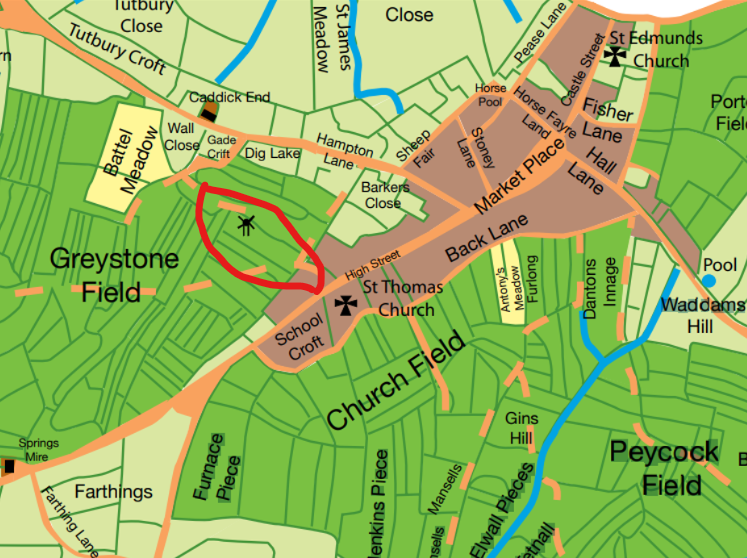

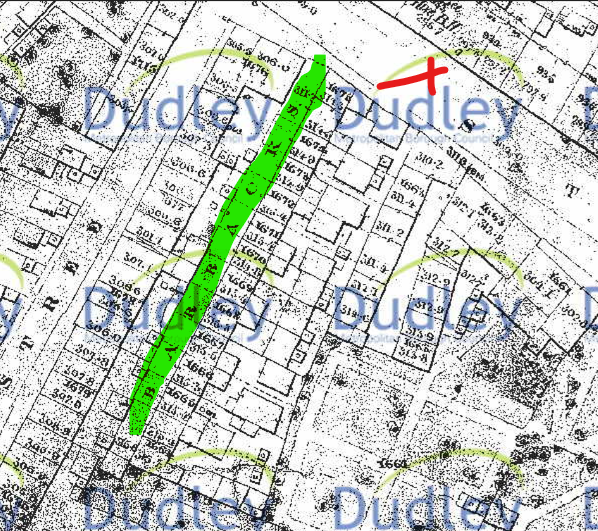

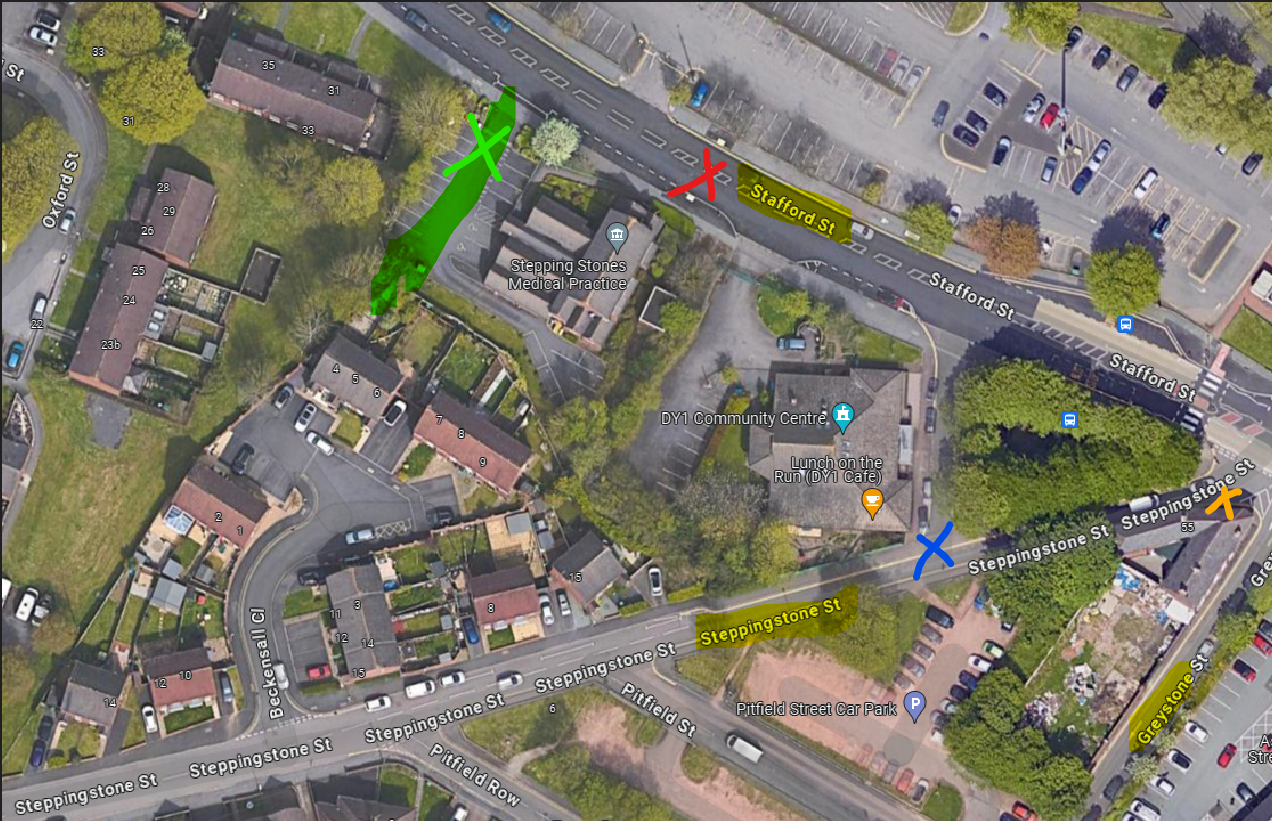

A coal miner, Francis lived on Stafford Street in Dudley for the whole of his married life until his death. Stafford Street leads from upper High Street and was once part of an ancient track leading to Wolverhampton. It was named Field Lane, then Mill Street, after the windmill that once stood on the land, and finally Stafford Street.

Deeds dated 26 August 1845 at Dudley Archives outline a mortgage of dwellings and premises at The Barracks and Dock Lane from Stephan Dunn to John Palmer to secure £100 with interest. These papers outline, “a piece of land lying in Greystone Fields … out of lane called stepping stone or Dock Lane … said messuages or dwelling houses are situated at a place called The Barracks near Mill Street”.

Today, the names Stepping Stone and Dock Lane exist with Steppingstone Street running into Dock Lane.

The Barracks would not have necessarily been former military barracks but some kind of communal living accommodation. Twenty-five households and a stable were registered at the Barracks in 1851. Francis Jeavons, a coal miner, his wife, Mary Ann, a nail maker, and six children made up one of these households.

The housing conditions were extremely poor. The Birmingham Daily Gazette reported that they found the houses in the Barracks:

in miserably dilapidated condition, and some of them not fit for occupation. The out-houses (within two yards of the back doors) were running over with filth, and the adjoining ashpits topful. In close proximity to these places are the workshops of the nailers. It will not be surprising, then, that fever should be raging in the locality. There was one case of fever at a house which had some part of the roof off. In another hovel was a nailer, his wife, and six children, all suffering from severe attacks of fever. There were two or three other cases, but the most distressing was that of poor woman, ill from fever, who lay upon a bed of straw, in the corner of a gloomy chamber, devoid of the least particle of furniture. Crawling about the helpless woman was a naked child, uttering piteous cries.

A case of child neglect in 1913 at 14 The Barracks indicates that the living conditions at The Barracks still echoed those described in the Birmingham Daily Gazette in 1870 and that not much had changed in the intervening years. The family lived in a “wretched tenement … deplorable from dirt, damp and dilapidation”:

1864

By June 1864, Francis was 44 years old. The pig iron and the iron trades had been hit by low prices and the iron and coal masters proposed a reduction of 6d a day in coal miners’ wages from the end of the month. Miners in Dudley, Francis included, started to strike in protest in early July. The strike spread across the Black Country and South Staffordshire, involving as many as 25,000 miners at its height. A struggle between the colliery owners or masters and the miners, the strike pitted striking miners against working miners. During the course of the strike, acts of intimidation became increasingly violent and the courts dealt with such cases with varying levels of severity.

Read more about the 1864 strike here.

Explosion

The strike was into its fourth month by October. At four o’clock in the morning on 10 October, a tin breakfast can filled with explosive was thrown at the home of John Haywood at Springs Mire in Dudley. John Haywood was a doggy (foreman) at the Old Park Colliery owned by the Earl of Dudley, located at what today is the Russells Hall Estate. He was not on strike and was working at the reduced wages.

John Haywood slept at the front of a two bedroomed house and was woken up by the sound of breaking glass. As he jumped up out of bed, he saw a flash of gunpowder and then heard a loud explosion followed by the sound of footsteps running from the front door. A miner’s tin breakfast can had caught the upper cross section of the downstairs window frame on the top of the shutters. It did not go through the window but exploded badly damaging the side wall and windows. John, his wife Catherine and eight children were sleeping in the two bedrooms but none were injured.

John Haywood found a hat about two feet from his door and a cork with part of a fuse that miners used for blasting. After inspecting the damage, John Haywood reported the incident to the police at Springs Mire and a police sergeant immediately visited the scene. The next morning, different parts of the breakfast can were found.

First Arrests

An ironstone miner, Francis (Frank) Bennett, was taken into custody shortly afterwards and brought before Dudley Magistrates on 17 October charged with being involved in the attempt to blow up Haywood’s house. Bennett was remanded for a week but released on 19 October when a striking collier called Edward Wilkes, who had worked under John Haywood before the strike, was apprehended and charged with being implicated in the explosion.

Edward was arrested as he had revealed to Francis Bennett’s cousin that Francis was innocent of the charges and that he was the one who had been involved in the incident meaning only to frighten John Haywood. The cap that had been found two feet from the scene of the explosion was his.

After his release, Francis Bennett was never charged again with involvement in events in 1864 but was killed at the age of 40 just a few years later in 1871 in a fall of stone at the Grubbin ironstone pit in Netherton.

Edward Wilkes lived on Dock Lane, five dwellings down from the Jolly Collier public house on the corner of Dock Lane and Stafford Street. When arrested at his home by Superintendent Burton, he reportedly declared, “I can’t go agin it, I’ll go with you”. He was brought up on remand at Dudley Police Court on 26 October and committed to trial at Worcester Winter Assizes in December.

St Thomas is on the right.

Edward Wilkes – Trial

At the trial, Dudley police constable, Charles Minchin, testified that he had brought Edward Wilkes his dinner shortly after his arrest when Wilkes informed him that two other men had been involved in the explosion. At that time refused to give their names. Wilkes confirmed that he had been drinking with “little Franky” Bennett at William Hooper’s Hope Tavern before the explosion but reiterated that Francis Bennett had not been involved with the event.

St. Thomas church – RK Barbers in this photograph.

This also shows the junction into Stafford Street.

Edward Wilkes’ home was approximately at the tree line on the left.

In his testimony, Wilkes said that he had returned home from the Tavern at around a quarter to three in the morning. He named two striking miners, Francis Jeavons and Isaac Foxall, who he claimed then knocked at his door and persuaded him to “go for a walk”. He had gone with them but did not know where they were going and only knew of the gunpowder when Francis showed it to him saying that he was going to frighten John Haywood. He had then refused to go further and had lost his cap when he followed Jeavons and Foxall leaving the scene of the explosion.

Edward Wilkes denied he was guilty and insisted that he was entitled to a pardon as he had given police information to find the true offenders. The judge nevertheless sentenced him to twelve months’ imprisonment with hard labour, stating that the sentence could have been at least ten years’ penal servitude.

Francis Jeavons – Special Sessions

Edward Wilkes was reported to have displayed considerable penitence and remorse before and after the trial. His statements to the judge had implicated Francis Jeavons, a near neighbour he had known for 20 years.

Further enquiries were made by the police who reported Francis had absconded, ‘leaving the county’. Francis later testified that he had been working in Lancashire. The police visited Francis’ residence on Stafford Street on Sunday 26 February 1865. Francis was not there but surrendered himself to Dudley magistrates the next day, declaring that he was innocent but was giving himself up as he had heard the police were looking for him. He was remanded until Friday 3 March when he was brought before a special Sessions at Dudley. Edward Wilkes was brought from Worcester County Gaol in charge of Thomas Crosbie, the Deputy Governor, to give a witness statement.

Wilkes appeared to be ill and reportedly had been seriously ill in prison. He gave evidence that he had been at Hooper’s liquor vaults (Hope Tavern) on the night of 10 October from around six o’clock in the evening and that his wife joined him from around eleven o’clock until about three o’clock in the morning when they went home intending to go to bed. About ten minutes after they got home, they heard a knock on the door. Eliza Wilkes opened the door and Francis and another collier on strike, Isaac Foxall, came into the house asking Wilkes to go for a walk. Wilkes, the worse for drink, firstly refused to go but was finally persuaded to join Francis and Isaac.

The three then followed a route that took them down Dock Lane into Wellington Road turning to Springs Mire, a distance of over a mile.

When they were about fifty yards from Haywood’s house, Wilkes claimed Francis took a bottle with gunpowder from his pocket saying that he was going to frighten John Haywood. Francis and Isaac continued to Haywood’s house but Wilkes refused to go any further.

About five minutes later, there was a flash and then an explosion. Wilkes maintained that he lost his cap as he fell down running to catch up to the other two men running from the scene.

The testimonies appear confusing and contradictory at times:

- Wilkes contended he was able to walk home unassisted although he also testified he had been drinking for six to seven hours and that at the same time he was also too drunk to know what he was doing.

- His wife, Eliza, testified she had told Jeavons and Foxall that her husband was “so tipsy he couldn’t stand on his legs”. He then walked a mile to Haywood’s house and returned home. Eliza stated her husband got home between four and five o’clock in the morning.

- Eliza also contended that Francis Jeavons had come to her a few days later on 19 October, the day her husband was arrested, saying, “Don’t cry Eliza, you shan’t want for money. We will gather some to help and support you and your family.” She claimed she had not seen him since.

- Mercy Davis, Wilkes’ daughter, corroborated her parents’ testimonies. Mercy also claimed she had been at her parents’ home at three o’clock in the morning when Jeavons and Foxall came by, although she was married and her own home was on Cross Street located on the other side of Stafford Street.

It was also alleged during the Sessions that Eliza had been given a part of a reward offered for information leading to finding the offenders.

Francis Jeavons – Trial

Francis Jeavons was committed to trial at the Worcester Assizes on 5 March, indicted for:

unlawfully, maliciously, and feloniously by the explosion of gunpowder, damaging part of a dwelling house, in the occupation of John Haywood, on 11th October last, in the parish of Dudley, Haywood and nine other persons being then in the house.

At the trial, the details of the incident were once again presented and Edward Wilkes gave his evidence. Francis Jeavons asked him directly, “Wilkes, did I fire the powder?” and Wilkes replied, “No, I did not say so.” Francis denied that he had anything to do with the incident and stated that he could have witnesses to corroborate his statement if he had sufficient money.

Francis became exhausted and said that two prisoners in gaol had told him that Wilkes had confessed the offence to them. These prisoners were brought to court. Adam Cooper testified that Wilkes had told him that he had thrown the bottle with gunpowder when they were together in the prison hospital at Worcester. Thomas Brookes, on the other hand, denied that he had told Jeavons that Wilkes had informed him he had thrown the explosive.

The jury acquitted Francis of the felony but found him guilty of the attempt to commit the felony. The judge concluded that the offence was of a most serious character and one which had to put down with a strong hand. Francis Jeavons was sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment with hard labour.

Isaac Foxall (also reported as Foxhall and Foxton) does not seem to have ever been arrested for involvement in the explosion.

12 Months with Hard Labour

Francis was imprisoned at Worcester County Gaol. An inspection at the gaol in 1848 reported:

The prison is unlocked at a quarter before 6 o’clock in the morning; the prisoners are at labour from 6 to 9, when they breakfast in their cells; chapel is attended at 10; after chapel the prisoners labour till a quarter to 1. At 1 they dine and remain in their cells till 2, from which hour until 6 they are at labour again, when they get their supper and are locked up for the night. On all occasions communication between the prisoners is suppressed when possible.

… The prisoners are on the wheel about 10 minutes at a time, with an equal rest. The power of the wheel is applied to grinding corn for the prison, and occasionally for hire, under the management of a paid miller.

Consequences?

On completion of his sentence in 1866, Francis returned to Stafford Street in Dudley and resumed work as a coal miner. At the time of the next census on 2 April 1871, he was living at 40 Stafford Street with his wife and five of his children, his sons working as coal miners and his daughters as bagging weavers for the nail industry. He died just seven months later at his home at 40 Stafford Street on 7 November 1871, the causes of his death being chronic bronchitis and epistaxis or bleeding from the nose. He was 51 years old.

For whatever reasons, several of Francis’ children left Dudley at some time during the years following his death. His daughters, Ruth (Dorman) and Mary Ann (Rodway) and their families relocated to Wombwell near Barnsley and Ruth later emigrated to Illinois in the United States. His sons Francis, Andrew and Solomon became part of mining communities in Yorkshire – Francis at the mining village of Brampton Bierlow that lies between Barnsley and Rotherham, Andrew at Swinton near Mexborough and Solomon at Denaby Main, also near Mexborough, built by the Denaby Main Colliery Company to house its workers and their families. Francis’ wife, Mary Ann (Shaw), also moved out of Dudley to live with her son Solomon and his family until her death in 1892.

A number of Francis’ descendants did continue to live in the same streets in Dudley. In 1921, his grandson, William Grigg, the son of his daughter Sarah, and his great grandchildren can be found living at 3 The Barracks and working as coal miners. His daughter, Harriet, married Thomas Stevens, a fender moulder, and went on to live at 13 The Barracks until her death in 1930. The 1911 census records that she had given birth to 22 children and that 13 of these had died by that time.