I first came across the 1864 miners’ strike when I discovered my great, great, great grandfather’s brother, Francis Jeavons, had been imprisoned in 1865 and that his actions were a small part of a much wider event that was undocumented and apparently forgotten. The timeline of the 1864 strike below has been put together using various contemporary newspaper resources and accounts. It can probably be assumed that there were (many?) incidents that were not reported. Moreover, it should be mentioned that newspapers were not always unbiased in their accounts, often but not always, taking the side of the mine owners against the coal miners.

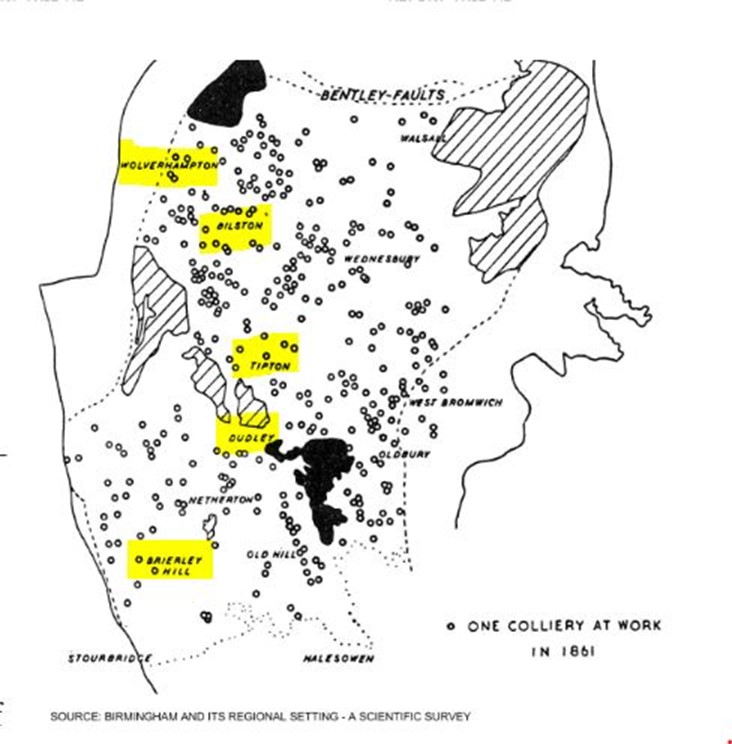

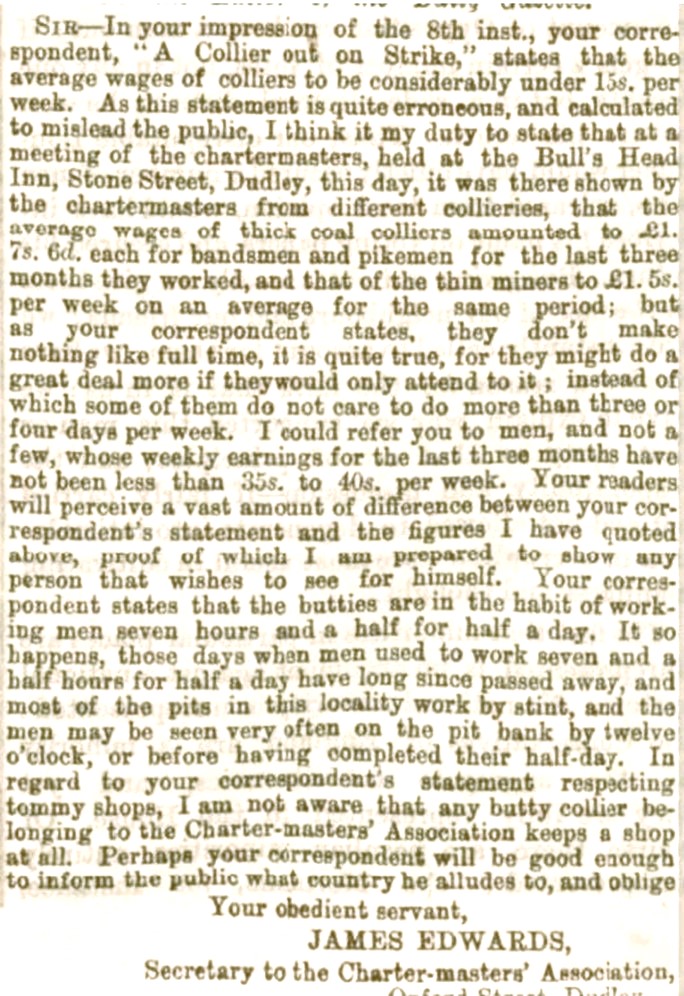

The pig iron and the iron trades were hit by low prices and on 10 June 1864 the iron and coal masters proposed a reduction of 6d a day in coal miners’ wages from the end of the month. Miners in Dudley started to strike in protest in early July. The strike spread across the Black Country and South Staffordshire, involving as many as 25,000 miners.

Reported as a struggle between the union and the masters, the strike had a negative effect on the iron trade with some ironworks at a standstill by September. Strong resistance began to emerge against attempts to break the strike or against those who returned or tried to return to work. Groups of men began to roam the Dudley and Tipton districts from around four in the morning inducing men not to return to work, “using every means within and not always within the law”.

As I publish this 1864 account in 2024 during the 40th anniversary of the 1984 miners’ strike, the parallels of the 1984 and 1864 strikes are noticeable. Both strikes were long and bitter. They both failed to meet their objectives, divided communities and remained long in the memory.

I came across a court case in which a Josiah Robinson was one of a group of petitioners seeking to make an election in Dudley in 1874 void. As he left the witness box, Robinson said something indistinctly about “64” that was heard by some of the reporters. Mr Powell, QC for the petitioners, asked him to explain what he meant:

“Robinson – They said I was a “64’” man.

Powell – Well, what did they mean by that, a “64 pounder”?

Robinson – There was a strike in 64.

Powell – Had you anything to do with that?

Robinson – No.

Powell – Well, what did they mean?”

The Dudley Guardian reported that Robinson tried to explain further but “did not succeed in conveying a very distinct impression of his meaning to the court”. The 1864 strike was evidently still the cause of some lasting memories, feelings and resentment in Dudley ten years later.

Thursday 8 September

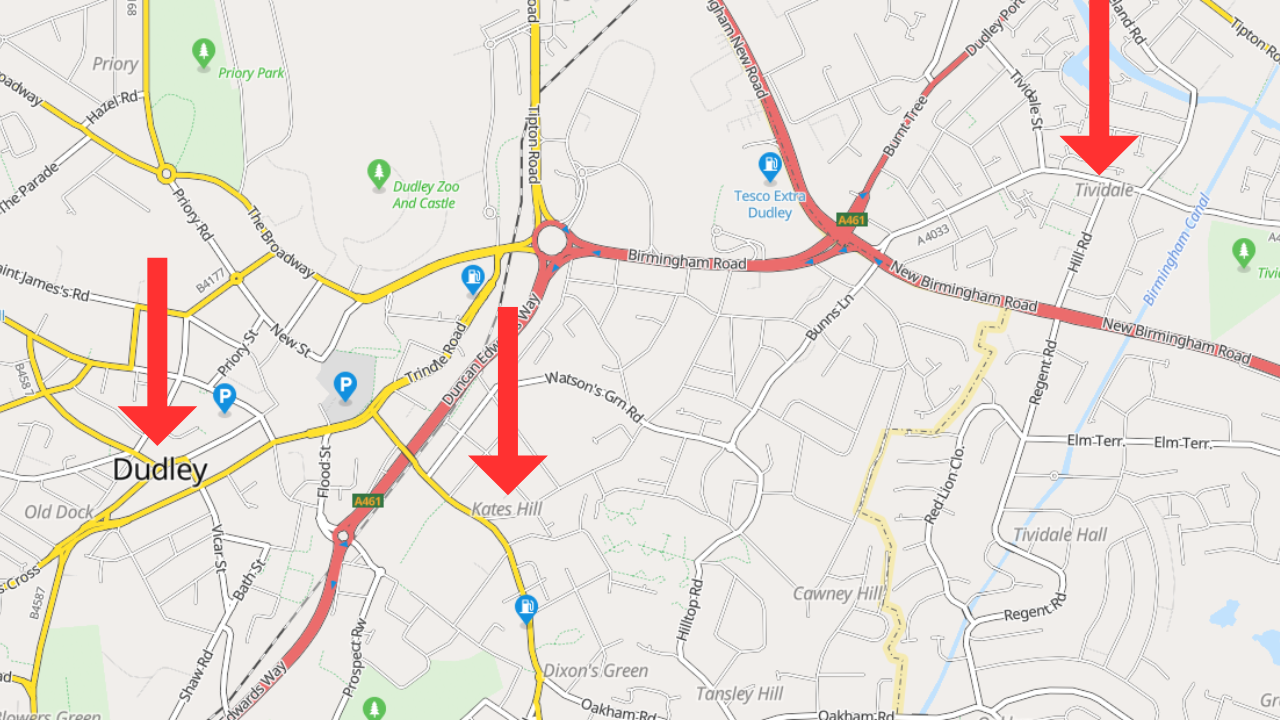

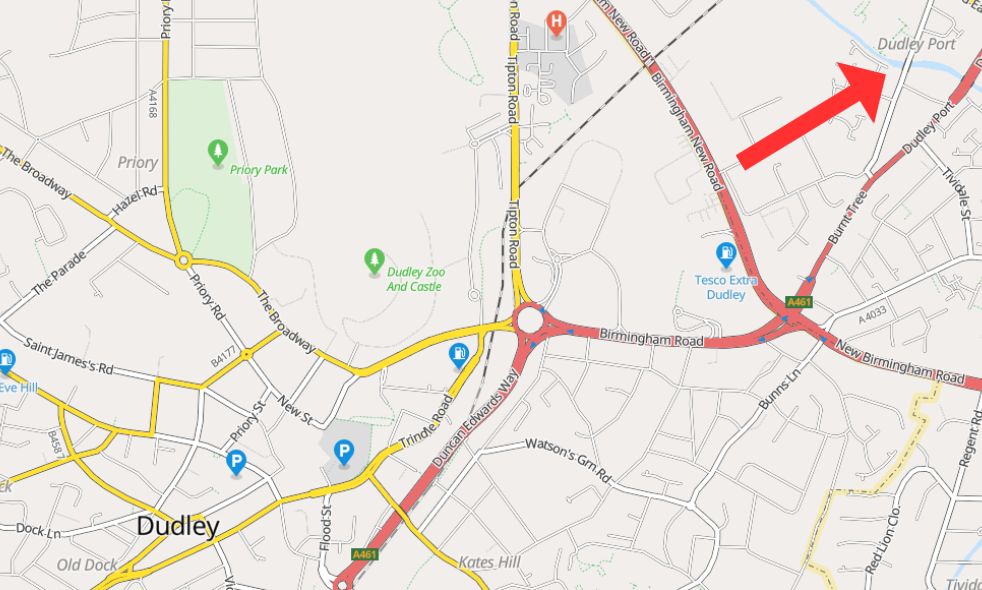

In the evening, John Westwood left his home in the Kate’s Hill area of Dudley to work at a mine owned by the Earl of Dudley in Tividale. On his way, he was met by a number of men and women. A large stone struck him between the shoulders and knocked him down. More stones were thrown among shouts of “black leg” and “let’s stone him to death and put him in the pool”. John’s brother, Isaac, was also prevented going to work when he left for work later that evening.

On the following Tuesday, Benjamin Marsh was sentenced to three months in prison with hard labour and Robert Pursell to two months with hard labour for their involvement in these incidents. Mary Ann Ashwin was charged with common assault for throwing the large stone that knocked John Westwood down. A witness, Sarah Brookes, who stated Mary Ann did not throw the stone also admitted that she had taken hold of John Westwood as she thought they ought “to stick out for the sake of their fellow creatures”. Informed that she may go to prison for such a remark, she replied that she might as well go to prison for three months and be kept rather than sitting at home and starving. Mary Ann Ashwin was fined 20s with costs or 14 days’ imprisonment with hard labour. John and Isaac Westwood were again threatened violently as they left the court in Dudley so that they needed police protection.

Sunday 11 September

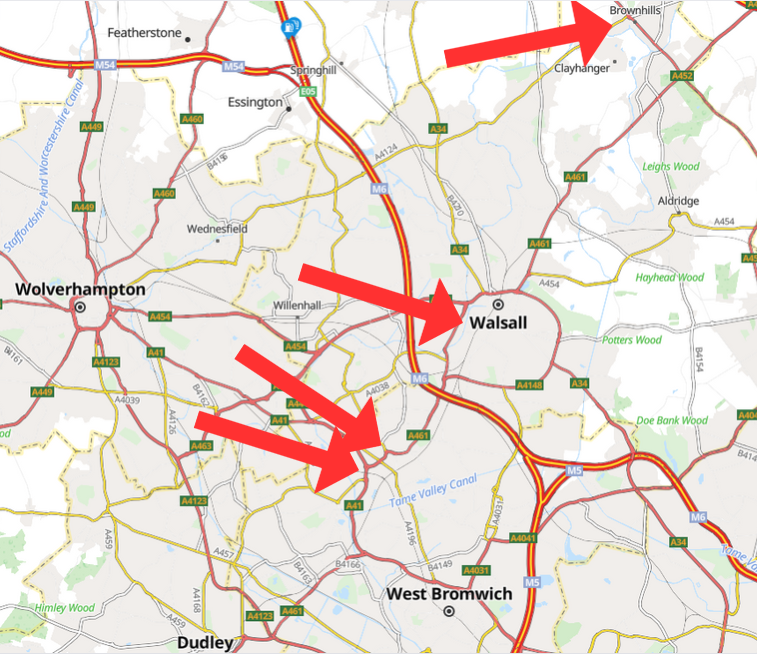

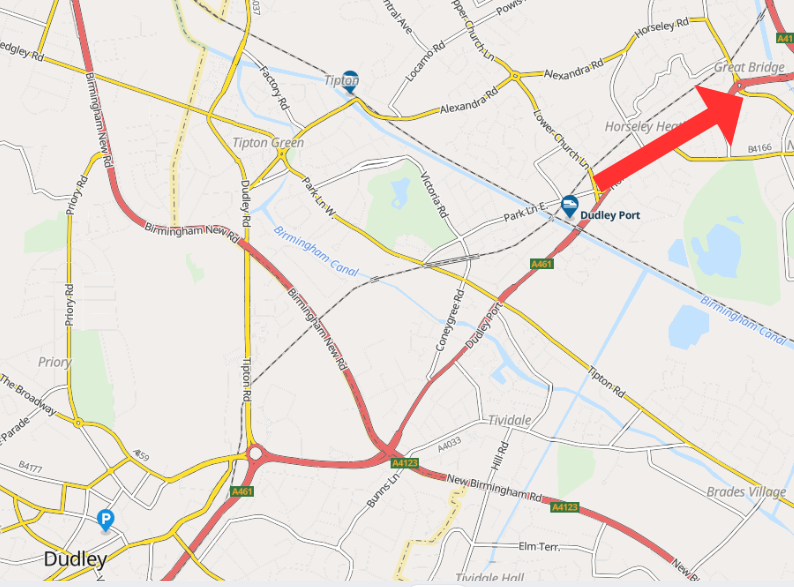

Large numbers of men and women gathered at Great Bridge just after midnight and then walked in a procession following bands of music to Brownhills, passing through Wednesbury and Walsall, a distance of 12 to 13 miles. The aim of the march was to persuade the miners in the Cannock Chase coalfield to cease work if coal were sent to an area where miners were on strike. The procession reached Walsall at about two o’clock in the morning. Estimates put the procession at between 3,000 to 4,000 people and it took 45 minutes for the crowd to pass through the town. Once the procession reached Brownhills, a meeting took place, attracting further numbers. On their way home, miners tried to raise money as they passed back through Walsall, either by selling sheets about the strike or by begging. This became a common practice with miners selling or begging as far away as Stafford.

Monday 12 September

A meeting was held at Bilston market and many miners marched from Dudley behind a brass band to attend this. Speeches were made for and against whether miners should give a fortnight’s notice of going on strike.

Tuesday 13 September

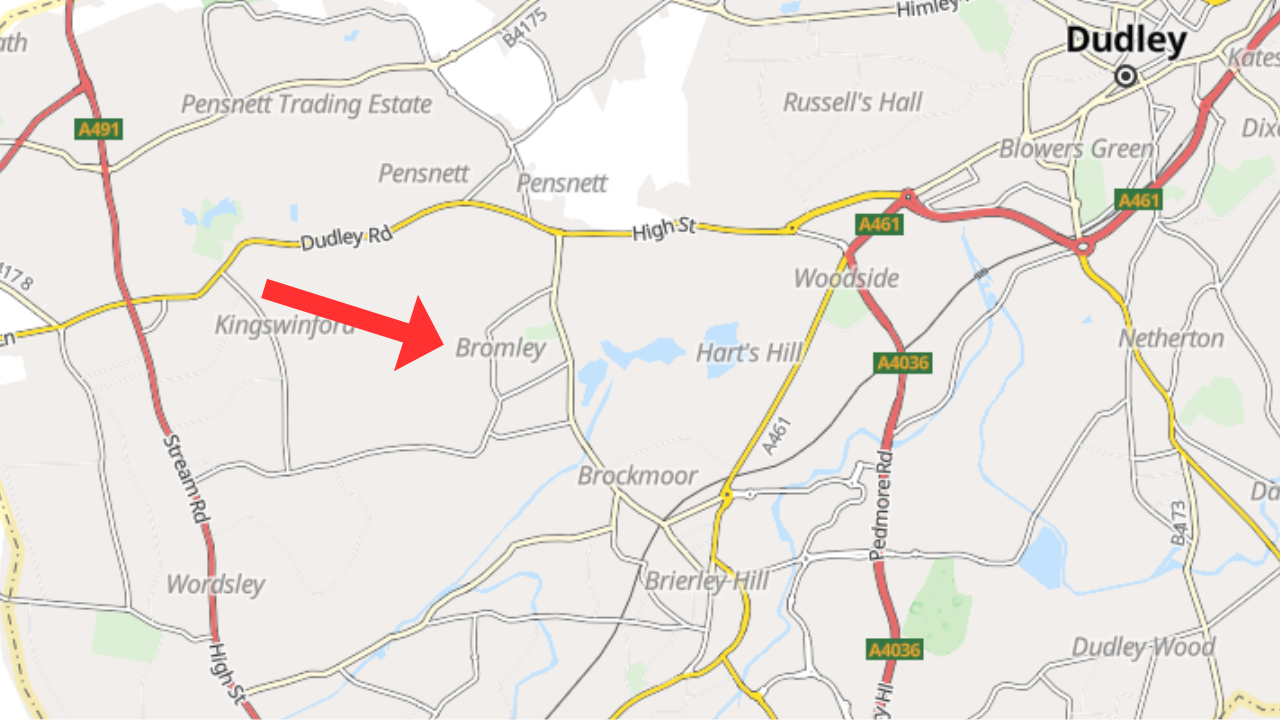

Joseph Blakeway, a mine manager at Bromley, was abused by crowds as he left work for a number of days and had to be defended by a group of police officers. Hundreds of men, women, boys and girls surrounded him on 13 September, shouting and threatening to throw him in the cut (canal). Elizabeth Wills told police that they would take care of him, put him straight and break his legs. On 23 September, Joseph was met by another crowd who hurled more abuse, shouting, “He’s coming; let us throw him into the cut; let us break his head”. Elizabeth Wills, Daniel Smith, Samuel Lloyd and John Morgan were sentenced to six weeks’ imprisonment.

Wednesday 14 September

The proprietors of coal and ironstone mines met at the Swan Hotel in Wolverhampton in order to discuss the incidents of intimidation and how to stop them. The owners considered the gatherings of miners illegal as the purpose was to prevent miners outside Dudley continuing to work.

Thursday 15 September

Major M Knight, Deputy Chief Constable of Staffordshire, issued a notice declaring that meetings held for the purpose of intimidating men on their way to work were illegal. He stated that the police had orders to summon and bring all perpetrators before the magistrates.

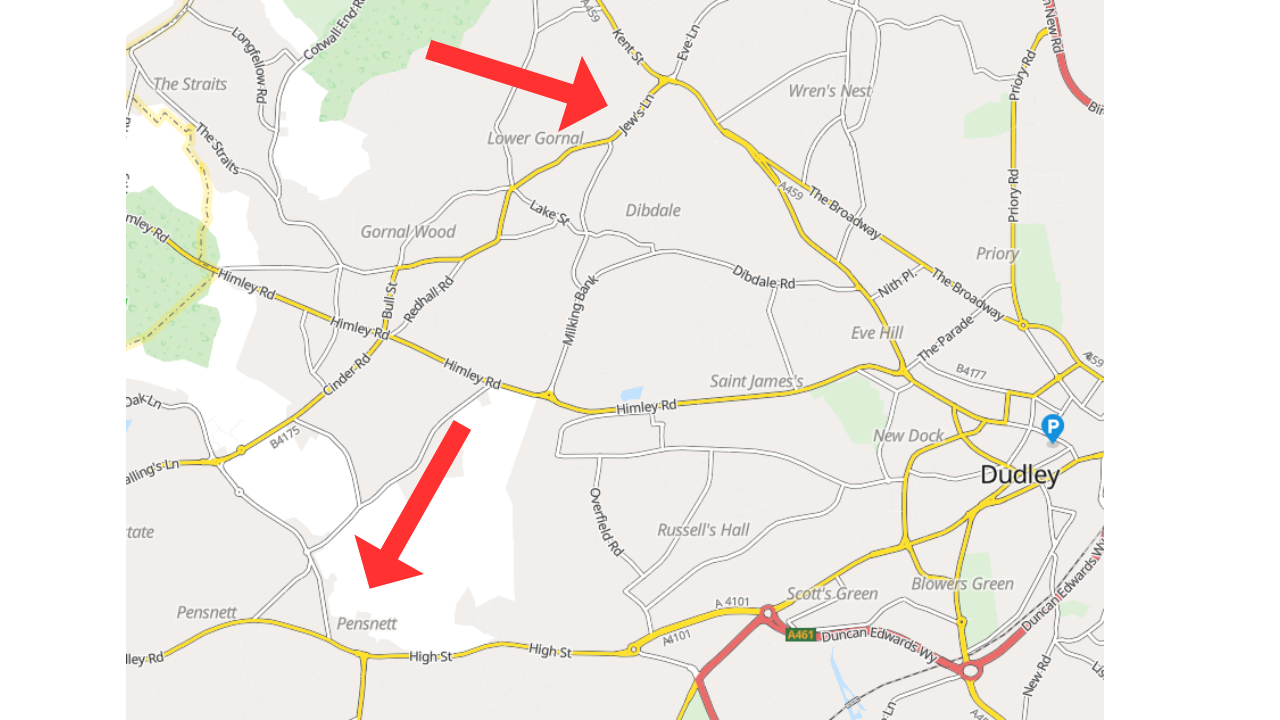

Wednesday 21 September

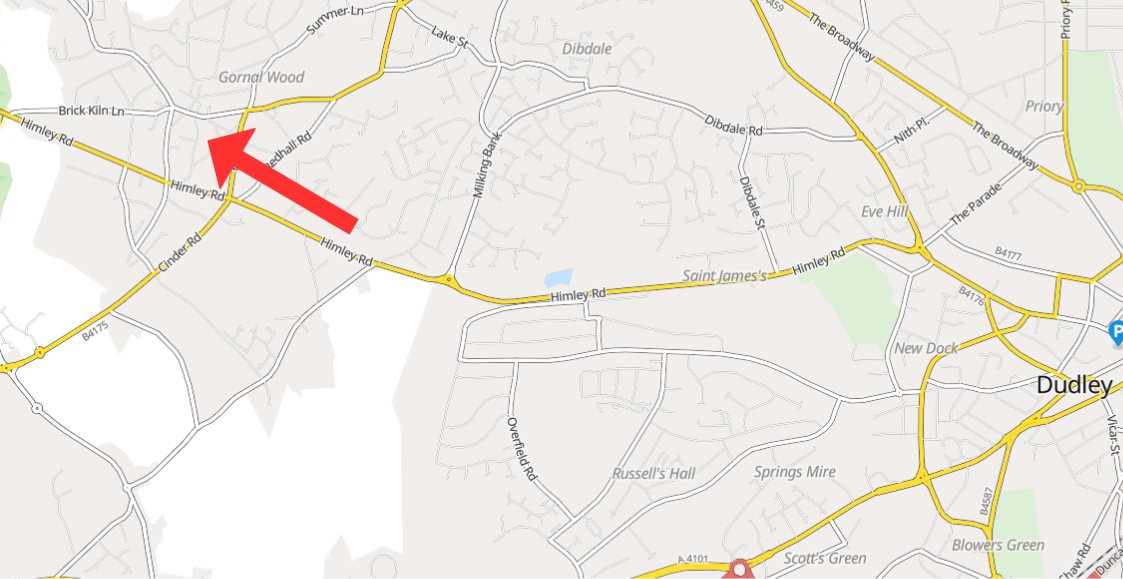

Samuel Tomlinson, a coal mine manager at Tansey Green Colliery, returned to his home on Jew’s Lane in Gornal in the late afternoon to be met by a crowd of around 600 people. It was later claimed in court at Bilston that the crowd cursed Samuel calling him a black leg and threatening him with injury or death. Five coal miners – James Beardmore, Thomas Burton, James Trevis, William Pritchard and Thomas Banks – were charged with being responsible for forming part of a crowd who had assembled for the illegal purpose of intimidation. All five men were sentenced to prison with hard labour for six weeks.

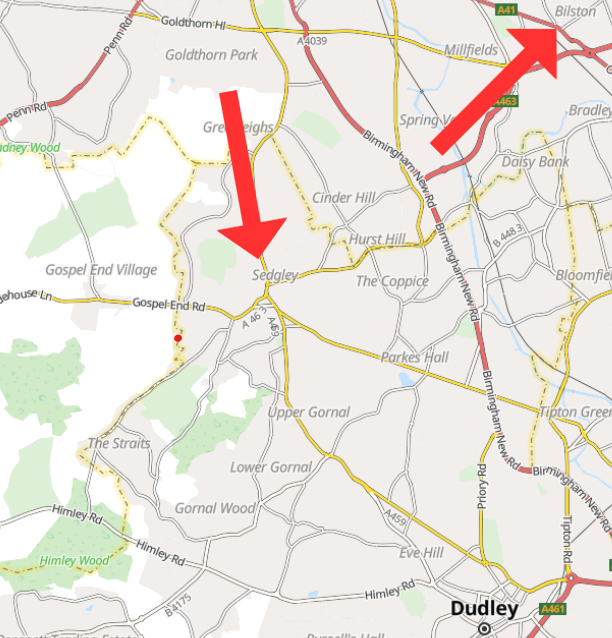

Thursday 22 September

Joseph Wild, a butty at the Butterfield Colliery in Sedgley, was threatened by a group of around 200 men in the early morning as he worked at the colliery and by another crowd of 40 to 50 in the evening when he went home. The magistrate at Bilston determined that calling someone a black leg was intimidation but released James Davis, Joseph Waterhouse, James Weaver and Joseph Love on payment of costs.

During the early part of the nineteenth century, the coal miners were not directly employed by the owners but by contractor, called a Butty. He engaged with the mine owner to deliver coal or ironstone at so much a ton. He employed the labourers required using his own horses and tools.

Coal Mining in North Staffordshire, Keele University

Friday 23 September

Another gathering assembled at the same Butterfield Colliery and numbers rose to around 200 as men working at the mine came to the surface at the end of their work stint. Thomas Bunn, a working miner, was followed by the crowd as he made his way home to the Coppice in Sedgley, protected by a line of police. The crowd played a drum and other instruments and carried bludgeons. Stones were thrown so that the police charged the crowd with their cutlasses and cleared the road. Seven men were charged with assault but the charges were dismissed as no assault could be proved.

Wednesday 5 October

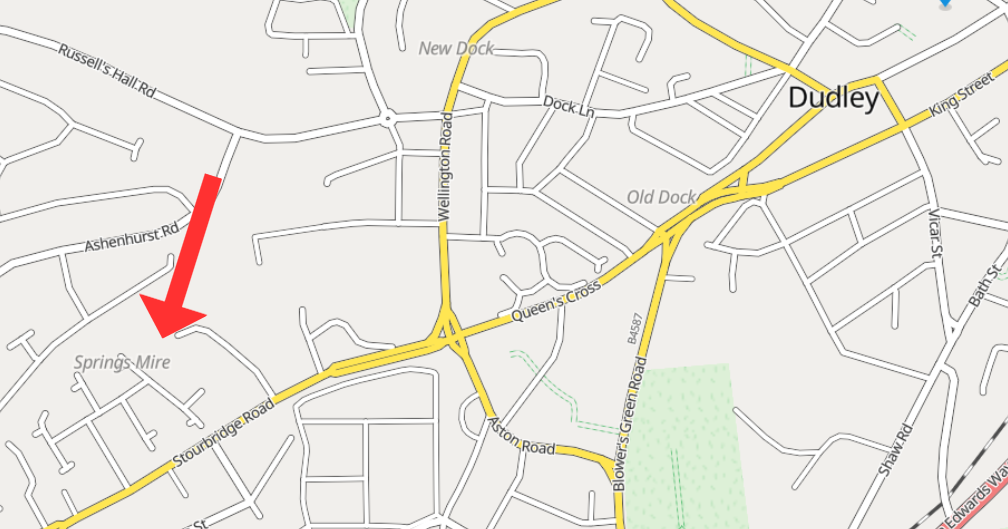

9,000 to 10,000 striking miners met at the Dock in Dudley. Dudley’s population at the 1861 census was 44,978 so that this must have been a huge assembly, representing around 22% of the town’s population. Speeches urged the men to hold firm and relayed messages from miners in other districts such as Wales encouraging the men to stay on strike and pledging subscriptions to support the strikers. The meeting was reported as ‘orderly’.

Thursday 6 October

After meeting strike leaders in Dudley on Tuesday and Birmingham on Wednesday, Lord Leigh, the Lord Lieutenant for Warwickshire, met leading iron and coal masters and strikers at the Hen and Chickens in Birmingham to see if any compromises or solutions could be found. No agreement was reached.

Saturday 8 October

The Staffordshire Advertiser reported that some groups of men around Dudley had returned to work in the previous week and had been protected by police. Police were now patrolling the streets from around three o’clock in the morning and strikers had developed the routine of meeting opposite the Limerick Inn on the Market Place at Great Bridge at four o’clock. After listening to speeches, they would disperse playing fifes, whistles and drums to different mines where men were working.

The Advertiser also expressed the opinion that the strike could not last much longer. Credit in shops was nearly exhausted and begging parties in different parts of the country could not get enough to support the large number of men on strike. The police were receiving complaints about strikers selling papers and threats towards those who would not buy them.

Monday 10 October

Joseph Roberts had returned to work at the Earl of Dudley’s Horseley Colliery in September and it was asserted that he had been frequently taunted and threatened by Thomas Marsh, alias ‘Pea’, a 29 year old miner on strike who lived near him. Joseph resided at Kettle’s Bank in Gornal in a dwelling that had just one bedroom. Seven people were sleeping in this room at four o’clock in the morning when they were disturbed by a noise. The bedroom window was forced open, a heavy object fell on the floor and almost immediately a loud explosion blew off the roof and broke the window panes. Nobody was injured and it was alleged that Thomas Marsh came at about five o’clock to enjoy the scene.

Thomas was brought before the magistrates in Sedgley and then at Bilston Police Court. It determined that the fuse used was one that was used by miners for blasting. Thomas’ home was searched for powder and his butty denied ever giving him any. A jury acquitted Thomas at Stafford Assizes in December.

Tuesday 11 October

On Elbow Street at Reddall Hill at one fifteen in the morning, a can of gunpowder was thrown through the kitchen window of Edward Greenfield, a miner working on reduced wages. The windows were blown out but nobody was injured.

At three o’clock in the morning, a tin breakfast can filled with explosive was thrown at the window of John Haywood, at Springs Mire in Dudley. Haywood was a doggy (foreman to the butty) at the Old Park, working at the reduced rate for the Earl of Dudley. The can caught the upper cross section of the window frame on the top of the shutters and therefore did not go through the window. The explosion badly damaged the side wall and windows. John, his wife Catherine, and eight children were sleeping in the house but none were injured.

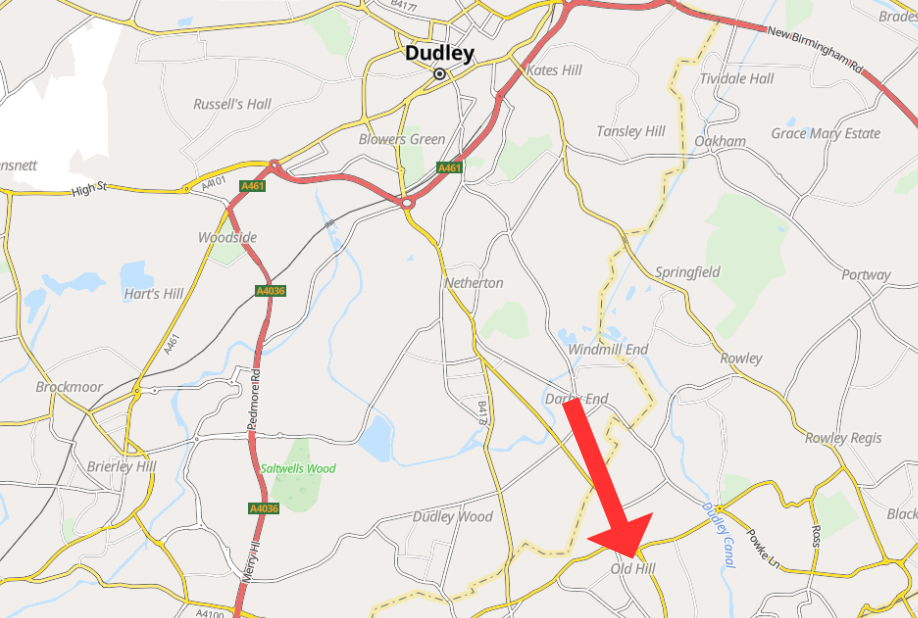

A can of gunpowder was thrown into a nail shop of the wife of a working miner, Samuel Williams, at Cherry Orchard, Old Hill at four o’clock in the morning. The nailshop was completely destroyed.

Large assemblies of miners in Gornal, Bilston and Wednesbury paraded round various collieries with drum and whistle bands between four and five o’clock. Most men in Willenhall (Wolverhampton) had reportedly returned to work.

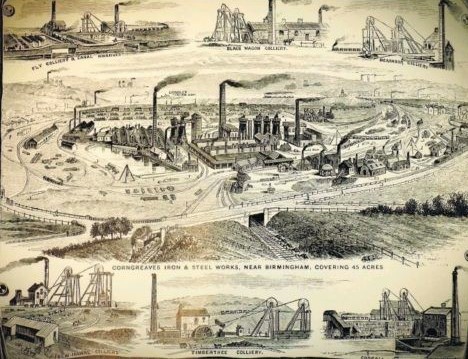

At nine o’clock in the evening, a breakfast can filled with gunpowder was thrown through a top window of the Timber Tree Colliery offices of the New British Iron Company at Corngreaves, where half the men were reported as working. A number of windows were blown out.

Wednesday 12 October

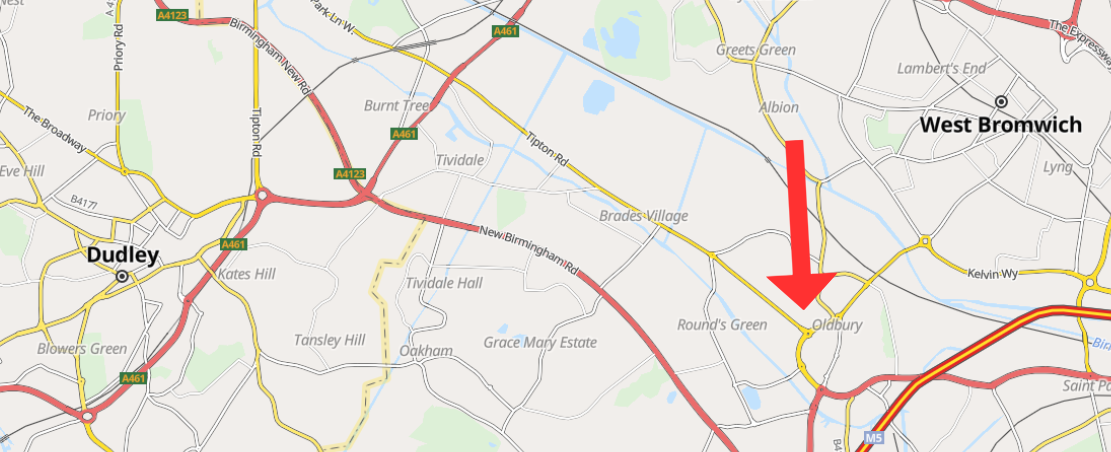

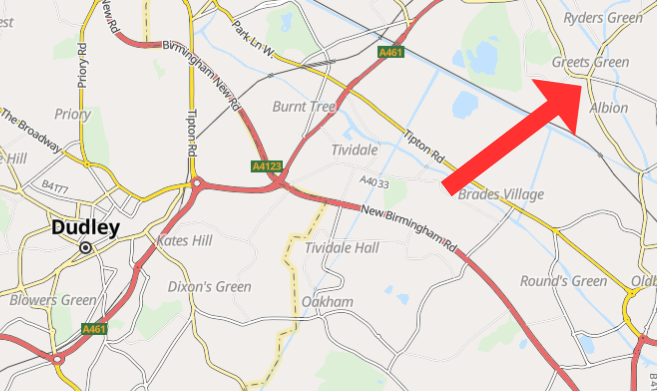

Henry Coggins, in the employment of Phillip Williams and Sons, No 11 Colliery at the Albion Works in Oldbury, was met by a group of 20 men on his way to work in the early morning. He was forced to turn back and threatened so that he did not go to work from Wednesday to Friday. Four miners – Thomas Barber, William Aldridge, Richard Hill and Joseph Latham – were committed to three months’ imprisonment with hard labour at West Bromwich Police Court.

A gunpowder explosion damaged brickwork around the boiler at Friary Colliery near Dudley Port during the night and was discovered the next morning.

It was reported that 80 Lancers had been ‘saddled up’ and ready to ride into the Black Country from barracks in Birmingham at a moment’s notice. In addition, volunteers were being kept under arms at Bingley Hall, Britain’s first purpose built exhibition hall, ready for any emergency.

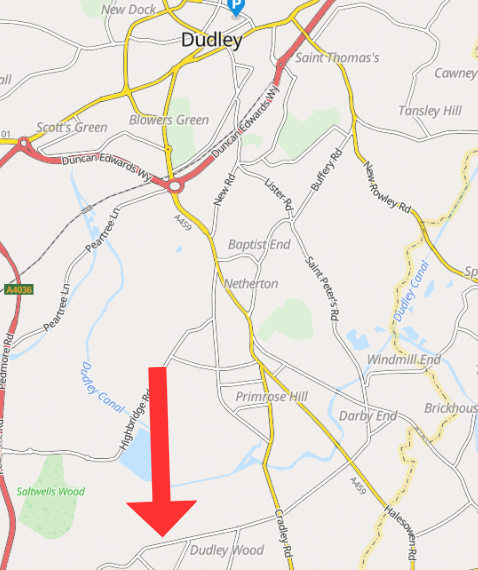

Thursday 13 October

At about two o’clock in the morning, a miner’s breakfast can containing gunpowder was thrown into Joseph Rowley’s kitchen at Mushroom Green. Joseph was a working miner at the Earl of Dudley’s Saltwells Colliery. There was a terrific explosion which shattered the brickwork in all directions and blew off parts of the roof. Joseph, his wife and a child were asleep in one bedroom and four children in another but were not injured.

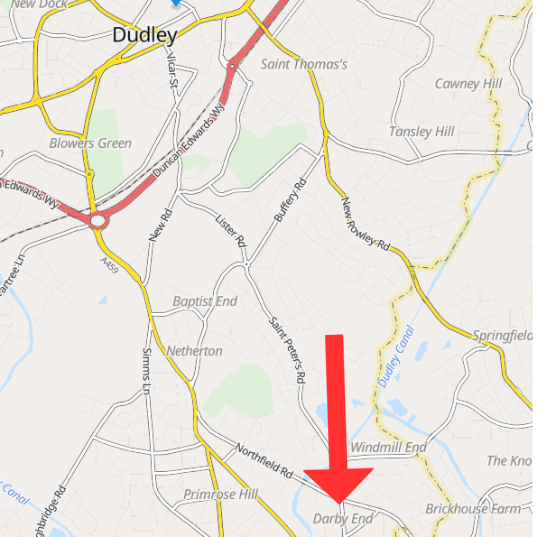

Daniel Parkes, alias ‘Trick’, a 31 year old collier from Double Row at Darby Hand was arrested later that day. A neighbour at Mushroom Green claimed he had been disturbed and had then witnessed Daniel and two other men accessing the entry leading to his house and Joseph Rowley’s. As it was a light night and the moon was shining, he claimed he then saw Daniel light the fuse with a match struck against the wall and then throw the can through the window. Witnesses on behalf of Daniel Parkes contended that Daniel had been drinking at the Rose and Crown at Darby Hand until about midnight returning home intoxicated and incapable of walking the distance to Mushroom Green. Daniel was found guilty at a jury trial at Worcestershire Assizes.

The judge concluded that Daniel had been convicted of a very serious offence and that his punishment should send a warning to everyone in the mining districts that they could not commit such outrages with impunity. He then sentenced Daniel to 10 years’ imprisonment.

The police visited collieries in West Bromwich early in the morning to meet two bands playing whistles and drums and around 100 strikers patrolling streets where men were attempting to go to work. Seven miners from the crowd – James Banner, Edward Perks, William Simms, Joseph Sheldon, Thomas Baldwin, George Simms and Benjamin Whitehouse – were arrested as the police held warrants for their arrests for intimidation on Tuesday 11 October. A further striker, Joseph Pugh, was arrested at his home.

A meeting was held in Dudley attracting between 5,000 and 6,000 men as well as women and children. After listening to speeches, the men marched through the town with bands playing and banners flying “in an orderly fashion”.

Friday 14 October

In Wolverhampton, onlookers were astonished to see twelve colliers on strike chained together, guarded by police armed with cutlasses, paraded from the railway station to the Police Court. All were charged with various acts of intimidation.

The first case concerned two brothers, William and Enoch Davis charged with assaulting Richard Cope, a doggy in the employ of Job Haines at Prince’s End. The brothers threatened Cope on his way to work and then assaulted him at the entry of his house on his return from work. As a witness claimed that Cope was drunk and had done his own share of taunting, actually initiating the fight, the case was dismissed. The next case was also dismissed as the incident had happened on 8 September but the arrest warrants had not been issued until 10 October.

The next cases involved James Banner, Edward Perks, William Simms, Joseph Sheldon, Thomas Baldwin, George Simms, Benjamin Whitehouse and Joseph Pugh for the arrests in West Bromwich on 11 October. All were sentenced to three months with hard labour and Joseph Pugh to a total of five months with hard labour.

THE COLLIERS’ STRIKE

The Daily News

“The Staffordshire colliers now on strike have published their statement of the most recent transactions in a letter to the Birmingham Daily Post.

It Is a melancholy document; and the speeches at the Oldbury meeting on Friday were melancholy; and everything connected with the suspension of an important industry, and of the means of subsistence of thousands of families, is melancholy. It is painful to think of the women and children, lately so comfortable in their houses, and so easy in their affairs, now sinking into misery as the season gives us a foretaste of the winter’s cold; but it is quite as painful to witness the mistake of the husbands and fathers, and the dutiful sons of widowed mothers, who either believe in their own minds, or are required by their leaders to declare that they are engaged in a virtuous struggle – are, In fact, defending actual rights which wicked men would deprive them of. This false notion of a right to a particular rate of wages is at the bottom of the whole mischief, It Is nowhere denied that the colliers and their families can live very comfortably on what they now refuse – 4s 6d – the nominal day nor that they did live comfortably (those of them who understood domestic comfort) on a shilling less, like the colliers In the rival districts of the country, who are living now on 3s 6d, a nominal day.

It is nowhere denied that the difference between the wages of two years ago and this year has occasioned the blowing out of many furnaces In the iron district depends on this Staffordshire coal. Yet these colliers cannot see – or, perhaps, are induced not to admit – that they can have no right to wages which their product does not yield. If they talk of their right to a certain rate of wages, the owners might equally well talk of their right to a certain amount of profit. If the business does not, in the actual state of the market, afford those profits or wages, It Is absurd to talk of rights. The thing cannot be had, and there’s an end; and to take a tone of virtue In demanding what is impossible is as absurd, in employer or employed, as It is melancholy to see the substance of comfort and independence thrown away for a delusive shadow. Unless these colliers can shut up all the pits in the country but those in which they work there is not a chance of success for them.

They have to a small extent succeeded in their scheme of intimidation; but on the large coal districts a little further off their proceedings can produce no other effect than of increasing the demand and improving the circumstances of the colliers who are wise enough to do the work of the time for the wages of the time. The tone of the colliers’ letter to the Daily Post and of the speeches at the meeting on Friday seem to show, either that the men are becoming angry and vexed at their own want of success, or that they have allowed themselves to be represented by men who intend to keep up the strife till it is quenched in the dust and ashes of poverty and misery. The notion that the employers will yield if the men will only hold out long enough is, in the particular case, so senseless and desperate that readers of the speeches and the letter will scarcely believe that such a proposal can come naturally and immediately from such men as the ordinary run of Staffordshire colliers. Whether they are really deluded, or only misled or intimidated, it seems equally strange that their friends and well-wishers can have hoped anything from the proposal carried between the parties by Lord Leigh.

As Lord Lieutenant of the county, he had engaged to preserve the public peace amidst the demonstrations of the unemployed. As a kind-hearted man, sincerely grieved at the sufferings of the destitute families of the colliers, he was anxious to try every chance of bringing employers and employed to an understanding. He, and many others, earnestly desired to see an end to the dismal processions of idle and impoverished men, with their dreary displays of flags which have no triumph, and bands of music which have no mirth In them. But this was no reason for bringing forward proposals which neither were practicable in themselves nor could have operated favourably If they could have been acted upon. It is mere trifling to ask the men to take the reduced wages for a fortnight or the present month, and the masters to return to the higher payment at the end of that time. This is treating the question as if the quarrel was about the sixpences of difference which would be paid or not paid for two or three weeks. If the iron trade will not yield the raised wages, and will never return to be what It was in the district, because the Scotch and Cumberland and Lancashire colliers work for the old Staffordshire wages, It is mere nonsense to ask the coal owners to take a bribe of two or three weeks’ sixpences to lose thousands of pounds afterwards.

Any description that Lord Leigh could give of the sufferings of the colliers could not but be met by the two remarks, that to give charity was one thing, and to work coal-pits at a hopeless and permanent loss was another; and that the hardships of men who could now be earning from 30s to 60s a week were voluntary. Thus much the masters could not but say, however they might refrain from all description of the injuries they were themselves enduring from the mischievous mistake of their men. The proposal failed, as it was sure to do; and it has been mischievous not only in enabling the men to fancy and to proclaim that they would have made some concessions, but in a way which is far worse for them in concealing from them the real nature of the struggle on which the destiny of their whole lives henceforth may depend. To ask the coal owners to pay away their capital in wages was hopeless enough; but It was something worse to sanction the notion among the employed that the case could be essentially different after the 1st of November, and onward, from what it was from July to October.

As always happens in such cases the would-be helper is reviled by those whom he would aid. The masters need not expatiate on their view of the intervention; it is understood without explanation. But Lord Leigh can hardly have expected an outbreak of wrath from the colliers. They are not, only very angry but the tone of their speakers is abusive. Well-intentioned peacemakers simply feel pity, for the insolence of disappointed and suffering men. Such regret as there is, is for having caused disappointment, and aggravated the suffering by delusive gleams of hope. The lesson is plain enough on the present and on so many previous occasions. There is no use, and no safety, in dealing with these collisions otherwise than in perfect sincerity, and with clearness of view and soundness of principle. The best friends of the Staffordshire colliers now on strike will be those who shall convince them that they can gain nothing by holding out for what is unattainable; and that it is absurd and morally deplorable to give the name of “rights” to desires which are impracticable. Unless the men and the mediators learn this lesson speedily, and the masters use all patience, and gentleness, and reasonable liberality with their men, there is nothing but ruin in prospect for the class of Staffordshire colliers; and their best friends will feel the most grief for a calamity as needless as it will be terrible.”

Tuesday 15 October

The Bilston miners finished their strike. At the meeting, the committee of the miners of the Dudley district vowed that they would “play on”.

At Halesowen Police Court, John Tristram was sentenced to 21 days’ imprisonment for assaulting Thomas Harris, a working miner at the British Iron Company, by stoning.

Wednesday 19 October

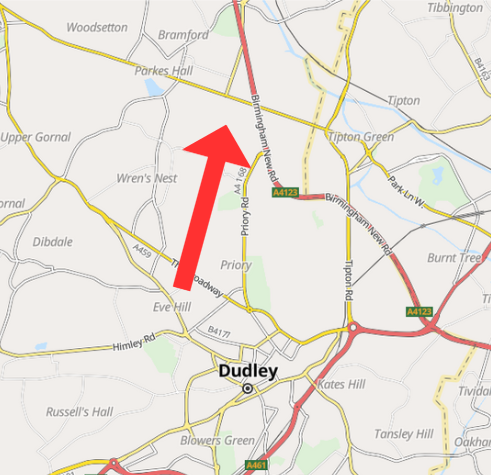

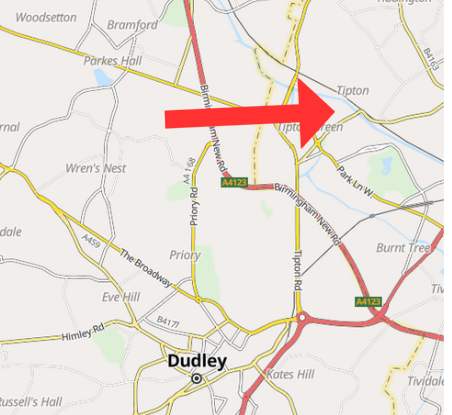

The Foxyards Colliery, owned by the Earl of Dudley, lay on the road between Dudley and Tipton. Stones were thrown at men working at the pit and carts had to be provided for transport.

Isaac Westwood appeared again for the prosecution at Dudley Police Court. Joseph Hunt and his son William of the Star and Garter at Kate’s Hill had attempted to conceal Samuel Rowley who was wanted for intimidation against Isaac Westwood. William Hunt was charged with assaulting Isaac Westwood and resisting a police officer and fined 40s and costs or, in default, two months’ imprisonment with hard labour. Joseph Hunt was charged with resisting the police in the execution of their duty and fined £6 and costs or, in default, two months’ imprisonment with hard labour. Joseph and William Hunt were also fined for another assault. John Turner and John Rowley were fined 20s or one month and John English and Benjamin Cooper were fined 40s or two months. John Rowley was fined an additional £10 and costs or two months’ imprisonment for threatening to shoot a police constable and pointing a gun at him.

Reports declared that the majority of men had returned to work at the Earl of Dudley’s pits, a proportion had returned in Wolverhampton and Bilston, and there had been a gradual return to work in West Bromwich, Oldbury, Tipton and Dudley Port.

Miners who had sought work in Durham and returned to Dudley were charged with neglect of work in Durham and sent back.

Police were guarding roads and the collieries.

Thursday 20 October

At about four o’clock in the morning, around 2,000 men armed with sticks and led by musical bands approached the Foxyards colliery from different directions. The police asked the men to stop playing drums and whistles on several occasions, but the men refused to do so. The police then blocked the road leading to the colliery and the crowd attacked. Nineteen people were arrested and charged with conspiracy to intimidate, appearing at Stafford Assizes in December. Additional charges included violence, assault and marching in military array along the Queen’s highway to the terror of a large proportion of the community. A jury found all the men guilty. Ten were imprisoned for one month with hard labour and the remainder were bound over to keeping the peace.

At a quarter past six, John Grazebook left home to work at the Earl of Dudley’s Tiger Colliery. He was challenged by thirty to forty men and boys who asked where he was going and proceeded to throw stones. William Raybould, who had been dismissed from the same pit before the start of the strike, was charged with intimidation. The charge was later dismissed at Oldbury Police Court as it was decided that Raybould could not be prosecuted on the basis of one man’s statement.

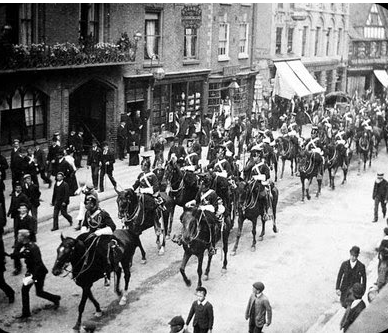

At about ten o’clock, about 1,000 miners marched out of Tipton and at midday, 6,000 miners armed with sticks marched through Dudley Port to Dudley to a miner’s meeting. The district was “thoroughly alarmed” and a troop of Lancers was sent from Birmingham.

Saturday 22 October

Large numbers of men mustered in Dudley and Tipton. A company of the 12th Lancers passed through Dudley at around seven o’ clock in the morning, moving onto Netherton, Saltwells and the British Iron Company at Congreaves. Strikers met to the west of Dudley and marched through the town at midday but did not play musical instruments as it was market day. The men proceeded to Tipton and attended a brief meeting there.

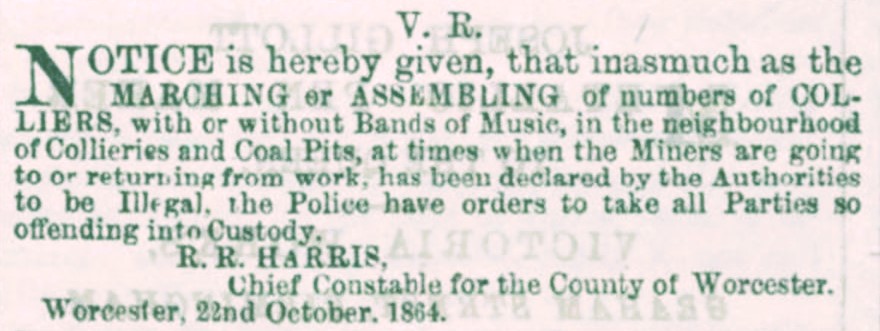

Dudley magistrates met in the evening and issued a notice, warning that marching and assembling in large numbers with or without music in the neighbourhood of collieries where men were working was illegal. The 12th Lancers remained at Tipton.

Michael Butler, a 34 year old collier born in Ireland employed by the British Iron Company, and Joseph Bingham, a 44 year old collier employed at Messrs. King & Co at Nether End, were next door neighbours in Cradley. Butler got into Joseph Bingham’s house when Bingham returned from work at around five o’clock in the afternoon, threatening that he would have “his guts out” if Bingham went to work and that his house would be blown up “by the roots”. Joseph Bingham was too afraid to go to work afterwards, particularly as he had been threatened previously on the road. Witnesses later corroborated the event at the Police Court in Stourbridge but Bingham stated that Michael Butler had never threatened him before and they were “always like two brothers”. Butler was drunk at the time but maintained that he was affected by drink as he had some blows to his head working in coal mines. As Michael Butler seemed sorry for his actions, the Bench sent him to prison for just ten days, stating that this should be warning to both Butler and others in the future.

Monday 24 October

There were no large assemblies of men at collieries where men were working. The strike was now largely confined to Dudley and Tipton where the military and police were in force.

15,000 people gathered at Tranter’s ground in Tipton, the largest meeting since the strike had begun. These included women, children and other workers who were sympathetic to the strike. The meeting condemned the police actions in stopping marchers playing music.

Wednesday 26 October

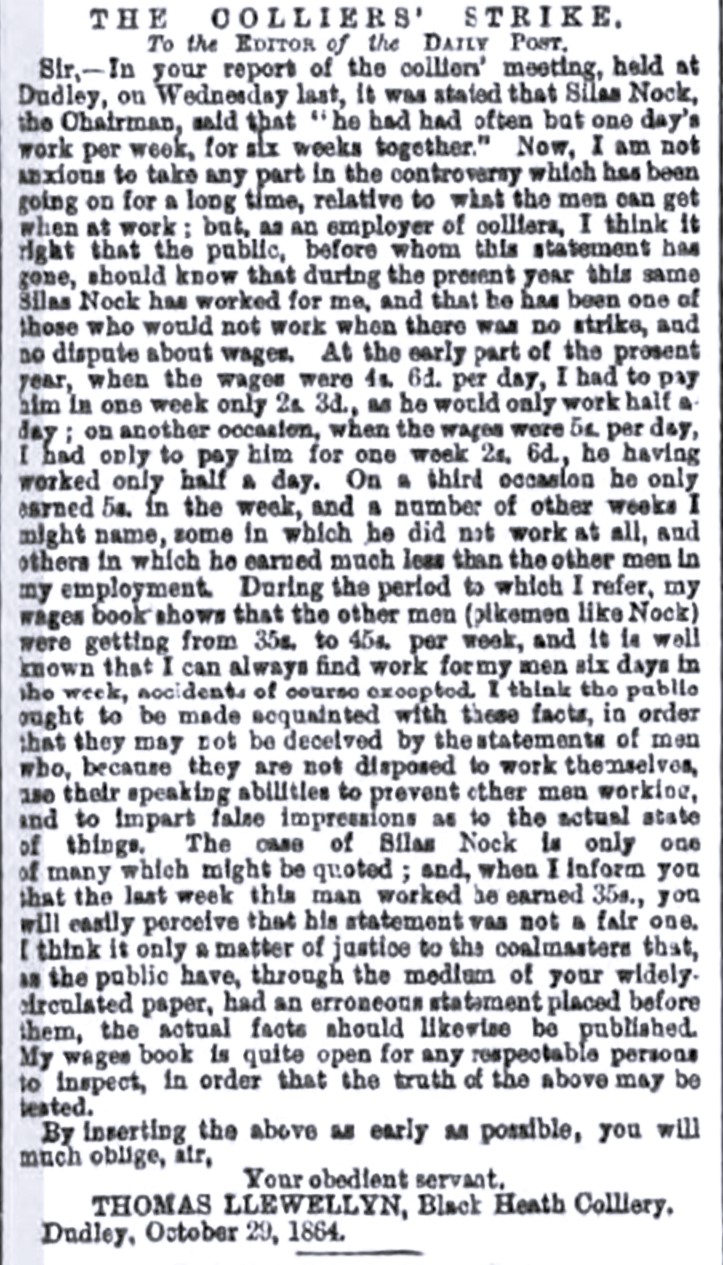

Over 3,000 colliers met at the Dock in Dudley at ten o’clock. They were firstly addressed by Silas Nock, a coal miner. He said that money was scarce but they had manfully struggled and he hoped they would still be successful. Danger was the common lot of the miner and there was less danger to life and limb in fresh air and daylight than in the impure air of the coal mine. He would rather suffer death than become a victim of tyranny. The next speaker was Mr H Bishop, secretary of the Union for the Dudley district, who went on to promise that the best legal advice would be made available to the men arrested on 20th October.

A reporter from the London Evening Standard attended this meeting:

“A meeting was held to-day at “the Dock,” Dudley, and as I have determined to take no statements on either side at second hand I attended it. A more unpromising spot for a public gathering I never saw. Situated on the outskirts of Dudley, at the other end of the town from that fine old ruin, which, wreathed in ivy and crumbling into dust, brings the romantic memory of the fourteenth century face to face with the smoky facts of the nineteenth, “the Dock”- why so called I know not, for there is no vestige of a canal within sight – is one of those undulating heaps of coal and iron waste which are rapidly changing the face of the country in these parts. Near at hand are the remains of the machinery at the mouth of a deserted pit; close by are a few cottages, wherein a desire for comfort has long struggled with a consciousness of penury; and under foot is a compound of wet coal-slack and bright green grass, which is as slippery as it is uninviting.

Ten o’clock was the time appointed for the meeting, and soon after that hour groups straggled in until there were from 3000 to 4000 persons present – men, women, and children, dirty, ragged, yet well- behaved. I had been told that if I attended the meeting I should be accounted as a spy, and that according to the standing usage of the mining districts I should have a cry raised, ” ‘Eave ‘arf a brick at him.” But, in truth, the people were as well-behaved as if they were at a May meeting in Exeter Hall; and they waited patiently until half-past eleven, when, at the bidding of one of their leaders standing in a cart placed in their midst, they began singing the ” Miners’ Hymn,” the lines being given out four and four, Methodist fashion, by the fugleman.

Then one of themselves was moved and seconded to the chair, and the speaking began with a few words from the chairman. I wish I could convey to you their speeches just as they made them; but in truth you would hardly print some of the remarks, not that they were coarse or indecent, but that they were so homely and, not to put too fine a point on it, vulgar. The chairman said God would defend the right. They had danger on the top of the land as well as below; but at any rate they had fresh air. Let them do right and behave themselves, but stick firm and be resolved to have their rights. They had better die than live victims to tyranny. Let them consider what their position was now, and what, if they were true to themselves, it would be in the future.

A miner named Bishop then apologised for pushing himself to the front, but he had to go away early to prepare a balance-sheet, to show what money was in hand to defend the poor fellows who were unjustly in gaol. They had employed the best solicitor in the district, and had engaged Mr. Kenealy as counsel. They had been called a lot of idle men, who ought to give way to whatever their employers chose to inflict upon them. But many people did not know what miners had to contend with. They on the other hand were practical miners, bred, as it were, in the bowels of the earth. They had to risk death there, and there was a doggie to hound them on, as there was a butty to hound him again. He then gave a description of the work in the pits, and of the bullying of the doggies as well as of the impure air that so seriously affected them. He was glad to acknowledge their debt to the inventor of the Davy lamp, who had saved many a score of lives. (A Voice — Many a thousand). He would like to see those who said they could earn enough money in a few hours a day at work with him in the pit (cheers and laughter), Certainly, in one long day a man might be able to do a day’s work, but next day he would fall as far short. He wished they could all agree to do a day’s work each and no more. (several voices, “That is plenty.”) God never made a slave, but the doggies had, and men had made slaves of themselves by their greediness and competition. The cry was that they would have to return to work or be starved to death. Why, they locked as well now as the first week of the strike. (A Voice – ”Better”). It was the gravediggers were beginning to cry out now! (laughter.) He and all the rest of them had gone often with but one meal a day, and they could again (cheers). The delegates were accused of making away with the money, but that was untrue (yes, yes). All had pleased themselves in the struggle. Let them just be straightforward and keep out of the hands of the bluecoats (a few of whom were present) (Bluecoats = police). Some people cried to put them all in gaol. If they were all put in gaol, another lot would spring up in their places. It was thought that when they did go to work they would have to suffer another drop soon; but he believed the masters had got such a lesson this time that they would not try it again soon. However; if they meant to go in, let them all go in together, and not drop in one by one.

The Chairman then gave some revelations of the butty system. He said the butties walked about studying how to grind the men working for them, and they got fat upon it. Those of them who were Bible readers would remember how, under the old dispensation, anyone who was deformed or had a hump was thrust out of the synagogue. For himself he believed a huge corporation was as much a deformity as a hump on the back (laughter). The colliers’ wives had to walk about without bonnets and the children without shoes that the butties might have hearty dinners (Voices – “That’s true”). It had been said that they did not honour their employers. But honour to whom honour is due. Let them give a fair day’s wages for work done, and then they would be honoured. How were men to live when they had to go into the pit six or seven times a week in order to make one day’s work (referring to the butties not paying for odd hours and turning the men out of the pit before they completed a “day”). By the last official report it was shown that the life of the miner averaged only 27 years and a few weeks. Let them have fair play while they did live. The Scriptures said that no one ought to keep a labouring man out of his hire, and those who did so would have to give such an account of their stewardship that they would wish they had never as much as seen money. It was said, “By the sweat of thy face thou shall eat bread” but it was not said that a dozen others not belonging to him were to live on a man’s labour. Several other speakers followed in the same strain; but these sentences will give you an idea of the way in which these meetings are conducted.

Today a man was brought up before the stipendiary at this place charged with throwing a hand grenade into a non-unionist’s house, and he was committed for trial, as the evidence was sufficiently complete for that purpose. But the men on strike reprobate all such practices, and do not contribute to this man’s defence.”

Thursday 27 October

Working men going by trap to Round’s Green pit were stopped by a crowd of 40 to 50 colliers in the early morning at ten minutes past six. Stones were thrown and threats were made. William Round, Joseph Roberts and Thomas Brooks were charged with intimidation. It was disputed at Oldbury Police Court that these men could be identified in the early morning light. Witnesses gave evidence that Roberts and Brooks were elsewhere and a doctor gave evidence that William Round was too ill to have been at the pit. Nevertheless, the Bench were satisfied the men were guilty and sentenced them to twenty-eight days in prison.

Saturday 29 October

Colliers working at Greets Green Colliery were stopped going into work. Isaac Preston, Thomas Millichip, Daniel Safe, William Butler, James Williams, Edward Jones and Samuel Millichip were charged with intimidation. The case was dismissed.

Wednesday 2 November

As men gradually returned to work, it was found that conditions in coal mines had deteriorated as they had been left standing during the strike. Samuel Skidmore, John Kerrison, Samuel Jones and Stephan Harris were eating their evening meal in the mine at Russell’s Hall Colliery when they were hit by a fall of coal. Samuel Skidmore was immediately killed. John Kerrison was extricated from the mass of coal alive and taken home with a fracture to the spine and a compound fracture to the left leg. He died later that evening. Samuel Jones suffered a back injury and Stephan Harris fractured ribs.

Friday 11 November

The Edinburgh Review reported that the strike has desolated the west Dudley area like a famine. In the middle of the summer, only fifteen or sixteen iron furnaces had been working, leaving around forty not working in the Staffordshire district. The Review concluded,

“The most painful feature of such scenes always is the tyranny with which the strike is conducted on either hand, by ignorant and selfish men, who constitute themselves leaders of the workmen. On the one hand, they ruin the employers by driving away their trade; and on the other, they ruin their own comrades by not permitting them to work for wages which would content them.”

Tuesday 15 November

A dinner was given by Sir Horace St. Paul at the Dudley Arms Hotel on Dudley Market Place. The subject for discussion after dinner was “how to bring the colliers to their senses”. Those who addressed the meeting expressed the views that the colliers would not be better off if they got more wages and that colliers should be taught the true relation of capital and labour. Sir Horace St. Paul summed up that he could not help saying the colliers were fools and that he deeply regretted that the strike had taken a large amount of trade out of the district. He only wished the men could see how much mischief they had caused and what he wanted to see was sympathy between the men and masters.

Thursday 24 November

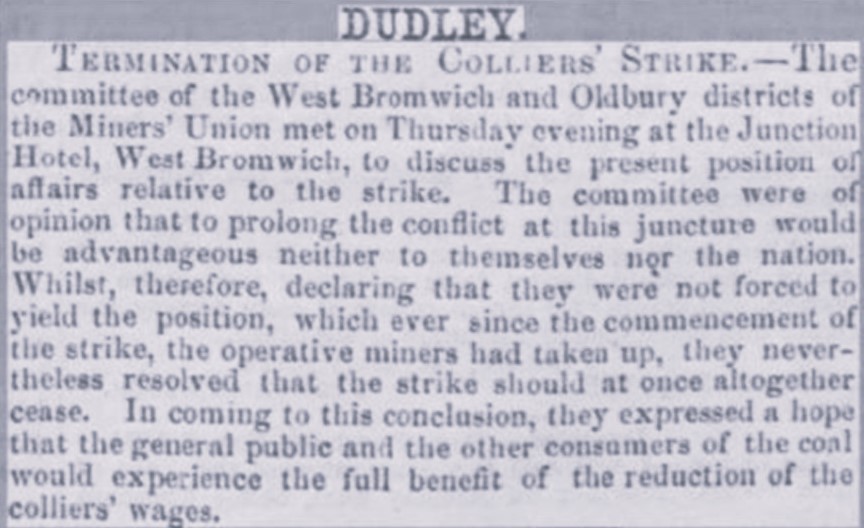

The committee of the West Bromwich and Oldbury districts of the Miners’ Union stopped the strike, agreeing that colliers would return to work at the reduced rate of pay.

Wow 🤯🤩 The depth of your research is just wonderful!

Holly, This research took me months but I found myself getting sucked in from the point that I found out that Francis Jeavons blew up a house and I wanted to know more. The atmosphere in Dudley must have been febrile in this period. It is difficult not to blame people for going back to work. They were poor and living in desperate circumstances so that returning to work must have been the alternative to starvation for many. On the other hand, it is easy to appreciate the feelings of those who remained on strike as winter set in.

Interesting to see the depth of feeling between families and men on strike and those going to work. Very similar to 1984. Desperate times. Capitalists thinking the poor miners would not be better off with increased wages and police with cutlasses too!

“colliers should be taught the true relation of capital and labour”

“Witley Court, The Seat of the Earl of Dudley

The mansion, a princely building, apparently of Bath stone, with noble porticos and flights of stone stairs on three fronts, stands in the centre of a fine park well filled with deer, beautifully wooded, and enriched with that charming inequality of surface which might be looked for in a locality within sight of the Malvern Hills. The flooring under the porticos just alluded to, consist of polished marble of different colours and patterns, flights of steps, some thirty yards in width, leading to a beautiful turf-covered terrace, supported by a stone-faced wall four and half feet in height, and’ traversed by gravel walk sixteen feet in width. Attached to the mansion is a beautiful conservatory ninety feet in length and sixty feet in width, with upright sides some twenty feet in height, ornamented handsome Corinthian pillars surmounted a curvilinear roof iron and glass.”

Worcestershire Chronicle, December 1864.

Well done Erica amazing research no wonder it took you so long. It could be made into a film. Terrible intimidation for the miners choosing to work, it becomes all to real when the brother of an ancestor is involved.