On Wednesday 11 March 1868, a ‘wet and boisterous day’, William Shaw stood at the top of the upcast shaft at Clattershall Colliery in order to communicate with three men and two boys working below.

Clattershall was mined using the ‘butty’ or chartermaster system, a contracting system between the mine owner and the butty to work a colliery seam for an agreed price. William was the son of the butty, Joseph Shaw, who had the contract with the owner, Edward Bowen. It was Joseph’s responsibility to arrange and pay for the necessary labour and he employed a ‘doggy’, Josiah Chivers, to supervise underground work. Josiah was one of the men working at the bottom of the upcast shaft.

At around 12.45pm William Shaw heard from Josiah Chivers. Everything was in order. 15 minutes later there was no signal from below and William Shaw gave the alarm.

This spread to the collieries and other works in the neighbourhood and a number of men arrived to assist. William Shaw and his father, Joseph, went into the workings of the colliery but the choke damp – the level of carbon dioxide – was so strong that they had to turn back and return to the surface.

For the next three to four hours, rescue workers strove to drive out the choke damp by throwing water and slack down the upcast shaft. The colliery owner, Edward Bowen, and his son assisted. At about 5pm, miners could finally enter the mine and when they did, they found five corpses.

These were the bodies of:

Josiah Chivers (33)

Thomas Hicks (33)

William Rhodes (20)

Joseph Rowley (14)

John Skidmore (13)

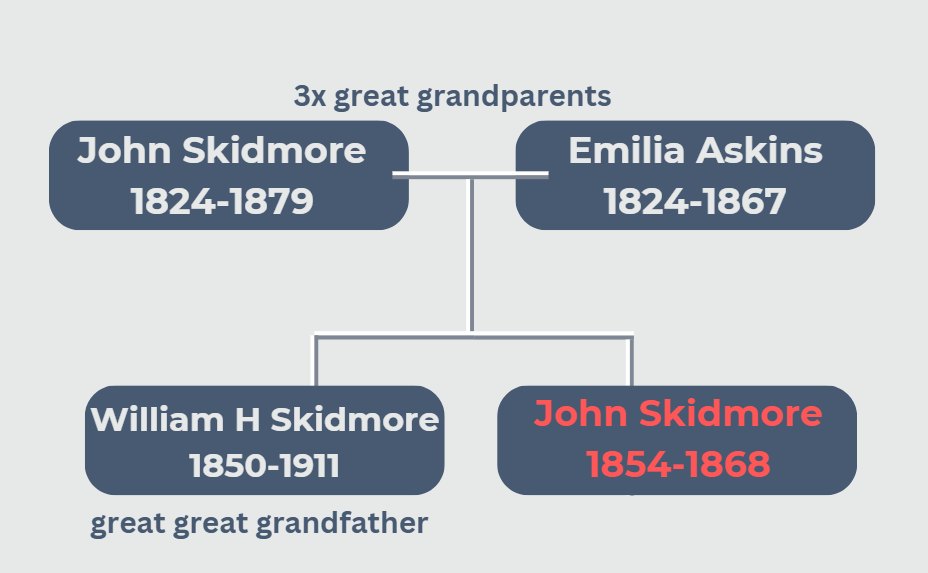

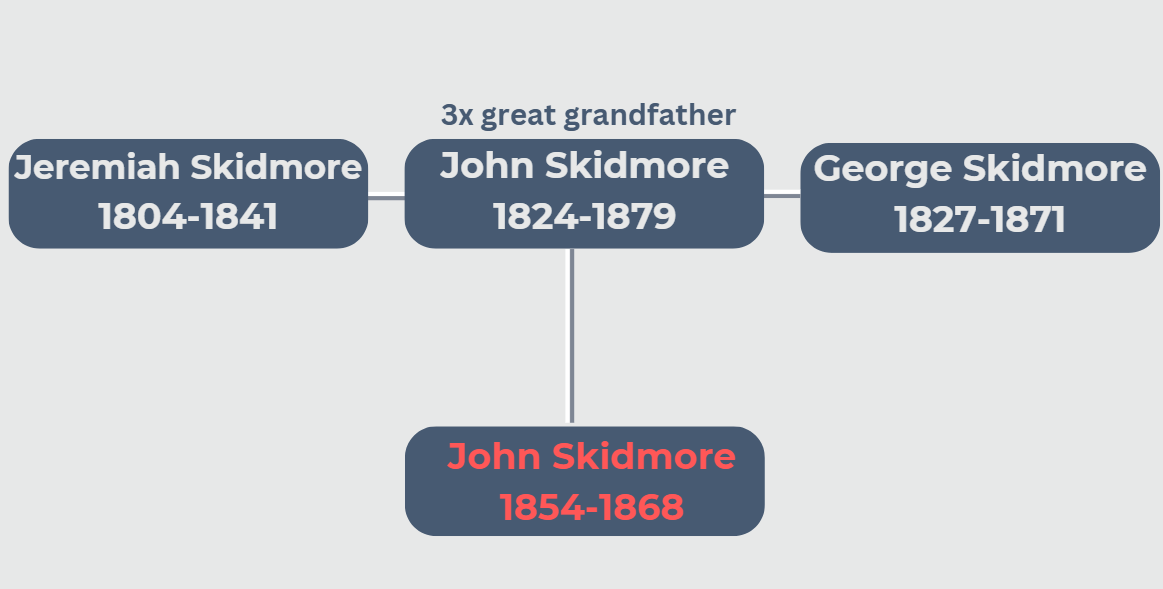

John Skidmore was the brother of my great great grandfather, William Henry Skidmore.

A boy, John had probably been working in coal mining for at least a year since the age of 12. A Mine and Collieries Bill of 1842 had prohibited coal mine work for boys under the age of 10 and the Coal Mines Regulation Act of 1860 had subsequently raised the age limit from 10 to 12.

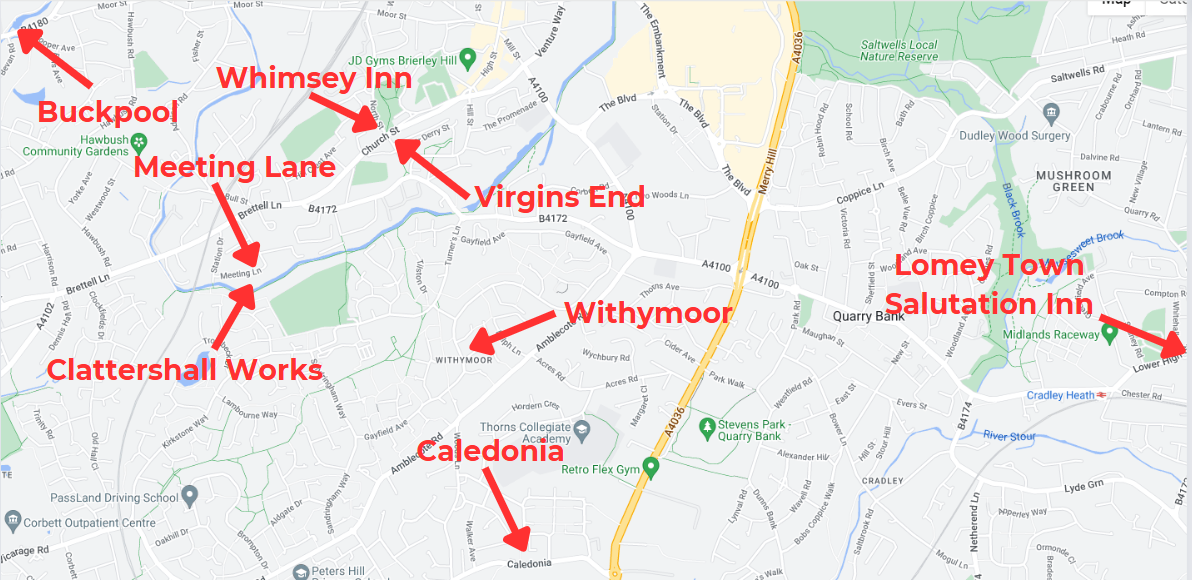

Clattershall Colliery

As part of Clattershall Works, Clattershall colliery employed 20-30 men and was an old mine located on the banks of Stourbridge Canal. The pit had been owned by the Earl of Dudley but had been taken over by Edward Bowen, a draper on Dudley High Street, just three years previously in 1865.

Edward Bowen took the decision to rework the pit to mine the ‘ribs and pillars’. Some of the old workings were permanently on fire and so were cut off with dams and new gate roads constructed.

The mine was a thick coal pit with three shafts – one for coal, one for clay and an old shaft used as an upcast shaft. This shaft was about 5 feet in diameter and 40 yards deep. A grate with a permanent fire was flung about 10 to 12 yards down into this shaft to improve ventilation below ground. Ventilation was vital to improve the flow of fresh air to the underground workings and to dilute and remove noxious gases such as carbon dioxide – ‘choke damp’, methane – ‘firedamp’, a mixture of carbon dioxide and nitrogen – ‘black damp’, or the burning smell of spontaneous combustion – ‘fire stink’.

11 March 1868

On the day of the fatal accident, one of the dams about 20 yards from the upcast shaft became leaky and it was decided to place sand against it and replace it. Joseph Shaw wanted to take the sand down into the mine in several loads and convey it by the usual roads to the dam, a distance of about 200 yards. The doggy, Josiah Chivers, refused to do this and insisted on throwing the sand down the shaft. Somehow Joseph Shaw allowed himself to be overruled by his doggy and took this latter action.

The grate with the fire was removed from the upcast shaft so that William Shaw could throw sand down the shaft. Josiah Chivers, Thomas Hicks, William Rhodes, Joseph Rowley and John Skidmore were put on the work to repair the dam once the sand had been thrown down and other men at work in the pit were ordered up to the surface.

Those repairing the dam died of asphyxiation. Josiah Chivers was found with his head on the dam and the others were found about 20 yards from the dam. It appeared that they had been attempting to make their way out of the pit.

The bodies were brought to the surface and after an examination by two medical men were taken to their homes:

Josiah Chivers to Lomey Town, Cradley Heath

Thomas Hicks to Meeting Lane, the road that ran alongside Clattershall Works

William Rhodes to Caledonia, Thorns

Joseph Rowley to Buckpool

John Skidmore to Virgins End, a back lane behind Church Road in Brierley Hill adjacent to South Street Baptist Church.

Family of Coal Miners

John Skidmore was born into a family with generations of coal miners who mined in the Brierley Hill and Amblecote areas for around 300 years. He would have been well aware of the hazardous nature of mining and that death or injury might strike on any day. Accidents regularly happened in the coal mines and many were fatal. 1,000 deaths occurred nationwide in mining in 1870 alone.

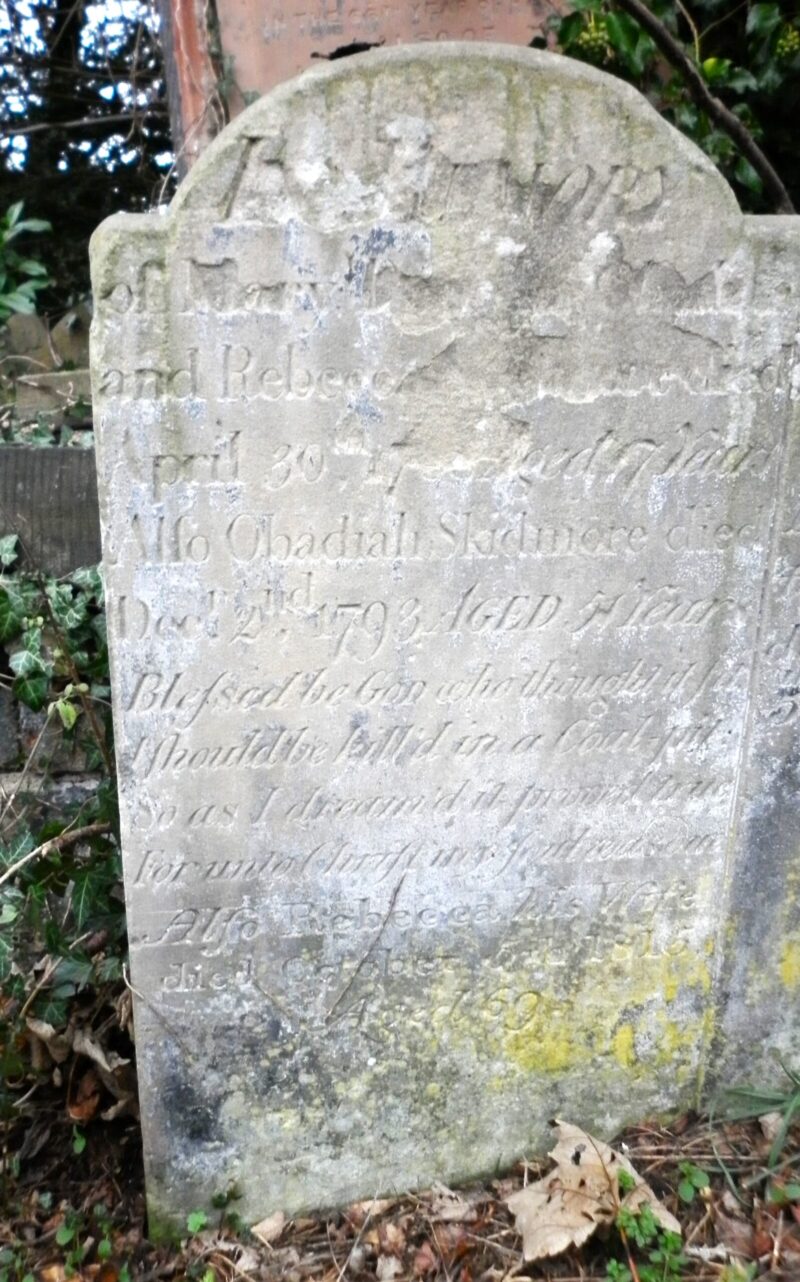

John’s great grandfather, my 5x great grandfather, Obadiah Skidmore, a coal miner in Withymoor, was ‘killed in a coal pit’ on 2 December 1793 at the age of 51. He was buried at St Mary’s church in Oldswinford two days later. The headstone at his grave carries the legend:

Blessed be God who thought it fit

I should be killed in a coal pit

So as I dreamed it proved true

For unto Christ my soul was due

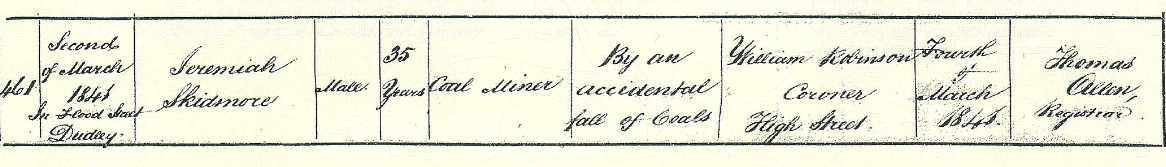

His uncle, Jeremiah Skidmore, died of injuries due to a fall of coal at the age of 35 at his home on 2 March 1841.

Another uncle, George Skidmore, was injured in a fall of coal on 13 October 1871 at Buffery Colliery in Dudley, now the location of Buffery Park, and owned by Howell and Mason. George died of his injuries a few weeks later on 6 November.

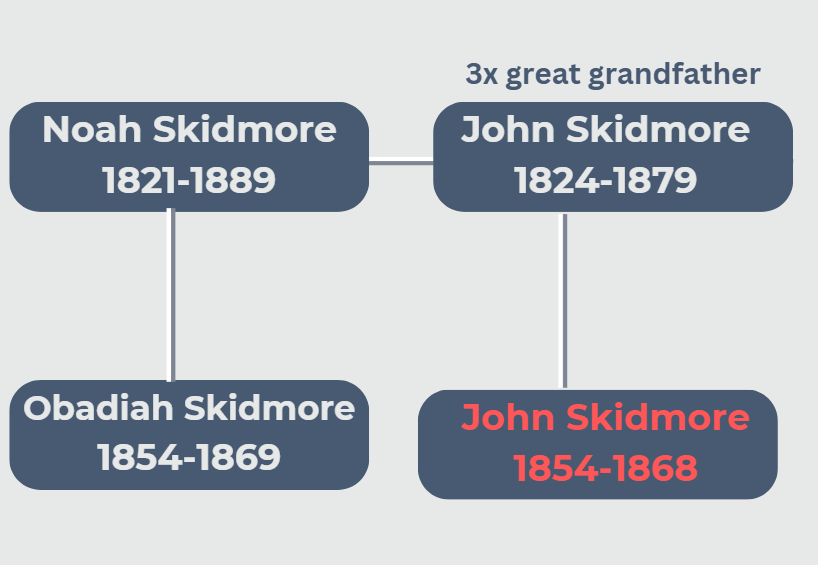

John’s cousin, Obadiah Skidmore, a boy of 15, died on 15 March 1869 at the Earl of Dudley’s Robin Hood Pit at Saltwells Colliery. Obadiah was employed to carry slack, refuse coal and coal dust underground. A lump of coal about four feet high fell burying him. A miner, Edwin Round, heard Obadiah call for help and rushed to help him. Edwin cut the coal off to extricate Obadiah only to find that he had already died.

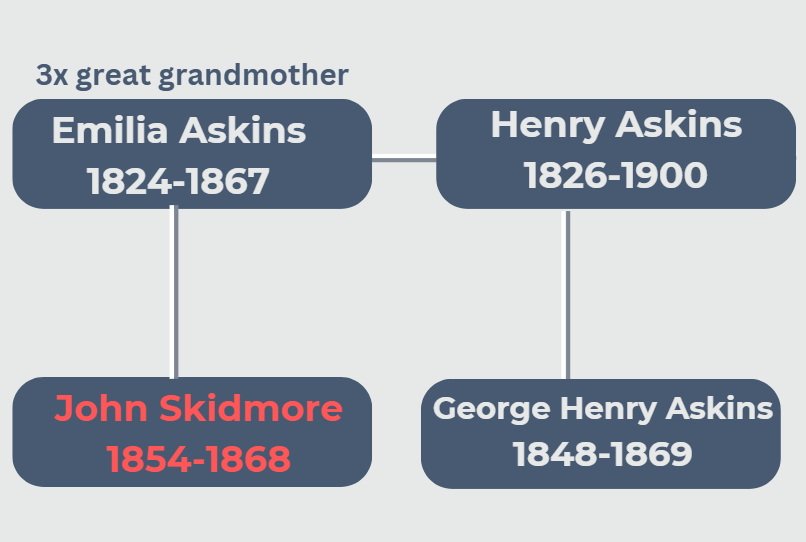

Another cousin, George Henry Askins, died a couple of months later at the Nine Locks Pit at Wallows Colliery in Brierley Hill on 8 May 1869. He was 22 years old. A boy, John Price, was working with George, ‘rating’ or pulling coals down from the sides of the pit. Another witness working in the pit, Richard Hoskiss, testified that George removed timber to help the coal fall. George instructed John to take some tools away and when John returned he discovered that George had been killed by a fall of coal from the roof.

Inquests & Burials

An inquest into the deaths of John Skidmore, Joseph Rowley and Thomas Hicks opened at the Whimsey Inn on Friday March 13. The Whimsey Inn was located on the junction of Church Street and North Street, almost opposite John’s home at Virgins End.

The bodies of the deceased were brought to the Whimsey Inn and the jury was given the opportunity to inspect them. Mr Baker, the Inspector of Mines – inspectors of coal mines had been appointed since the introduction of the Coal Mines Inspection Act in 1850 – and Mr Breakwell, Secretary to the Colliers’ Union, were also present.

Mark Underhill, a miner from Meeting Lane, testified that he had heard about the accident at about 3.30 on 11 March. He went to the pit and witnessed Joseph Shaw, William Shaw and Edward Bowen trying to get the fire in the upcast shaft started again. However, damp killed the fire whenever they put the grate four or five yards down into the shaft. After one rescue attempt failed, he later went underground with Thomas Gough, also from Meeting Lane, and William Shaw. They found all five bodies on the main road from the upcast shaft where they had been building a dam. The air was bad and the bodies were almost cold. He then helped to bring the bodies to the surface.

All the men and boys were buried at different churches two days later on Sunday 15 March. John Skidmore was buried at Brierley Hill.

The inquest continued at the Whimsey Inn on Friday 20 March.

Richard Growcutt, the ground bailiff for Edward Bowen, produced plans of the pit and workings and testified that Joseph Shaw had been given strict orders to keep the fire continually burning day and night on the upcast shaft to provide ventilation. Shaw had ensured him that he would see to this and told him he would not entrust the work to anybody else. Growcutt also stated that he had never heard of sand being put down an upcast shaft before and knew that doing so would ‘reverse the air’. Even if such an action were carried out, the fire should have been hung in the downcast shaft in his opinion. He considered Shaw’s decision to be an error of judgement and carelessness.

Four miners gave their testimony and all stated they considered putting the fire out to be dangerous practice.

William Cartwright of Rocks Hill in Brierley Hill worked Tuesday night to Wednesday morning and he reported that the air was good at that time. He helped to recover the deceased bodies when they were brought to the bottom of the downcast shaft.

Thomas Gough of Meeting Lane testified that the air had been good up to when he was working until noon on the day of the accident when Josiah Chivers told him to finish work as they were going to turn the air. Later he helped to recover the bodies with Mark Underhill.

William Sheldon of Amblecote reported that the air had been good but turned bad towards 12.30 as he was finishing work. He was the last man to come to the surface and at 1pm as he was going home from work he saw the fire grate on the bank. At that time, he reported that the air was bad and he felt that anyone still working below wouldn’t last long. On cross examination, he stated that he didn’t notice whether underground doors were open or shut as he was in a hurry to get out but added that, “It would not matter for the safe working of the pit whether the doors were open or shut”.

Mark Underhill repeated his testimony from the previous week.

Sarah Sutton, a bankswoman at the clay pit, gave evidence that she first heard about damp at around 1pm when William Shaw asked if she had heard any shouting.

Charles Bate, a banksman, had seen Joseph Shaw and Josiah Chivers discussing the repair of the dam in the morning when Chivers insisted on carrying out the work by putting out the fire and throwing the sand down the upcast shaft.

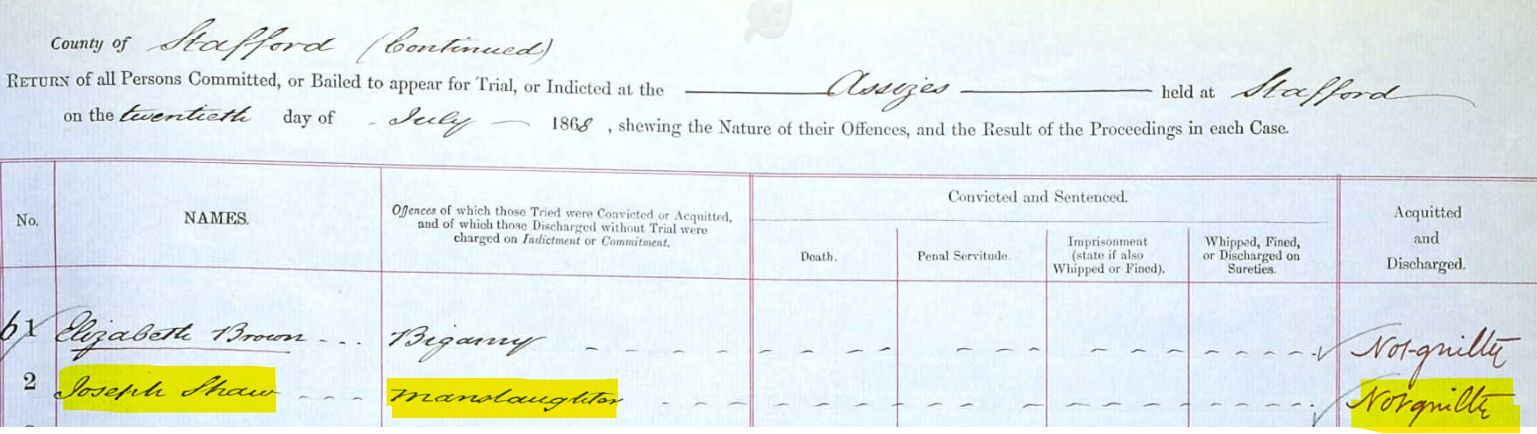

The jury returned a verdict of manslaughter on alleged neglect of duty and Joseph Shaw was committed to the next Safford Assizes. He was subsequently charged with causing the deaths of Thomas Hicks, Joseph Rowley and John Skidmore at Brierley Hill Police Court on Monday 23 March.

An inquest into Josiah Chivers’ death was held at the Salutation Inn in Lomey Town later that week on Friday 28 March. As two inquests had already been heard and a verdict of manslaughter given, the coroner asserted it was not necessary to go into the whole case and that this would save both time and money. The jury agreed to this and the inquest concluded that the deceased was found dead in a coal pit, having been suffocated by carbonic acid gas.

William Rhodes was buried at St. Mary’s in Oldswinford on March 15 and the burial entry at the church shows there was also an inquest into his death.

The coroner at the inquest into the death of Josiah Chivers mentioned that two inquests had been held so that the inquest on the death of William Rhodes must have occurred in the previous week at some location near to his home but this does not seem to have been reported by the local press.

Joseph Shaw – Trial

Joseph Shaw was indicted for the manslaughter of Josiah Chivers and four others at Stafford Crown Court Summer Assizes in July. The case occupied the court for six hours and the evidence was largely the same as that presented at the inquests. However, the defence contended that the accident in all probability had been partly caused by one of the men accidentally omitting to shut off the air doors on leaving work and ‘but for this misadventure the fatal accumulation of gas would not have taken place’. The jury acquitted Joseph Shaw.

Final Words

The question of whether Joseph Shaw was criminally negligent or not can be debated. There is no question that the men and boys were asphyxiated and their deaths could have been avoided. The miners who gave evidence at the inquests and trial clearly considered putting the fire out in the upcast shaft to be dangerous practice. Shaw allowed his butty to change his decision to take the sand into the mine down the mine roads rather than throwing it down the upcast shaft. His actions certainly did not constitute best practice and the juries at the inquests did conclude on the basis of the evidence that Shaw should be indicted for manslaughter.

The use of the butty system meant that the owner, Edward Bowen, was not held responsible for the deaths at his mine. At the inquests it was made clear that the miners worked for the butty and other witnesses worked for the owner. Indeed, it appears that Bowen was not at the inquests or trial when he was present during the attempted rescue of the men.

What is remarkable about this particular mining accident is not that a person was not ultimately held accountable for the deaths but that somebody was actually charged with something and that the case went to trial at Stafford Assizes. If an inquest into a mining accident did take place, it invariably determined a verdict of ‘accidental death’. Such was the case just a year later with the inquests into the deaths of John Skidmore’s cousins, Obadiah Skidmore – the coroner determining “there was not the least carelessness on the part of anyone”- and George Henry Askins.