Reading on a census form that my great great grandfather was a vermin trap maker was not the most strikingly attractive piece of my family history, at least at first sight. However, the more I found out about John Williams and his story, the more I became absorbed by the singular nature of the trap making industry and the group of entrepreneurs that led it.

In this process, I discovered that a number of myths, narratives and assumptions about trap making have developed over the years. The repetition of these stories has reinforced a belief in their validity and done a disservice to Wednesfield and the former trap makers.

Here, I outline and re-examine three of the narratives concerning:

(1) the historical timeline

(2) the nature of the industry regarding its management and products

(3) the dismissal of traps as inhumane and a forgettable part of Black Country history.

(1) A LONG HISTORY

Narrative:

Wednesfield emerged as a centre of trapmaking at some time towards the beginning of the 19th century. The industry declined towards the end of the century or in the first decades of the 20th century.

The definitive work on the history of traps and trap makers in Britain is Stuart Haddon-Riddoch’s book, “Rural Reflections” (2006), in which he lists all known British trap makers. It is worthwhile noting that a complete chapter of over 100 pages is allocated to the trap makers of Wednesfield alone. All other trap makers in all other areas are listed in another separate chapter of 75 pages.

Wednesfield was in fact a British and world centre of trapmaking over a period of at least 300 years, before and after the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution did give rise to growth but the birth of trapmaking in Wednesfield occurred long before.

O town of traps

The English Civil War between Royalists and Parliamentarians was fought between 1642 and 1651, culminating with the Royalist defeat at the Battle of Worcester on 3 September 1651. Charles II’s flight from Worcester took him north to Stourbridge and then on a circular route around Wolverhampton to Wombourne, Albrighton, Whiteladies, Boscobel House (where he famously hid in an oak tree while the estate was searched) and Moseley Hall which lies four miles north of Wednesfield.

A ballard celebrating this flight specifically mentions passing through Wednesfield or ‘Wedgefield’, a name my Dad still used for his birthplace and childhood home:

“In the noon of night they brought him,

Along the toilsome way,

And they passed through quaint old Wedgefield,

Where asleep the people lay.

“O town of traps!” they whispered,

“Your fame our foes will sing,

For they would fain a trap obtain,

To catch our Lord the King.”

This reference to the ‘town of traps’ would indicate that Wednesfield was already known as a centre or the centre of trap making in England by the middle of the 17th century.

In 1868, the Birmingham Daily Gazette stated that it was difficult to know exactly when trap making was first established in Wednesfield and no date had been recorded but there was ample proof that trap making had engaged the skill and labour of many generations. These generations belonged to local Wednesfield families prior to the 19th century.

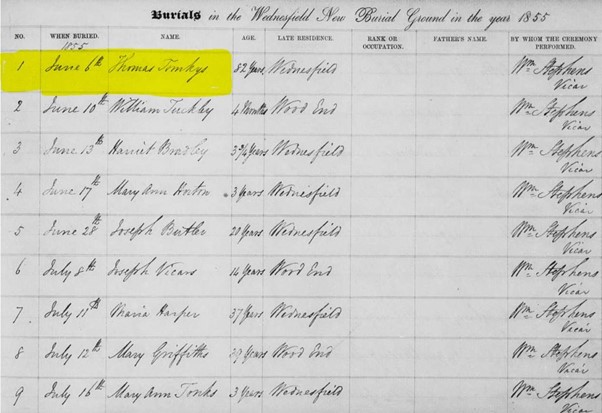

It is frequently speculated that trap making was developed by local blacksmiths and this is entirely feasible. Wednesfield was an agricultural village and blacksmiths may have developed skills to meet a need to exterminate rats, mice and other vermin. These skills were in all likelihood handed down from father to son. My 4x great grandfather, Edward Tomkys, born in 1757, and his brother Thomas Tomkys, born in 1773, were both Wednesfield trap makers who must have learned locally known skills, maybe from their father and grandfather.

In “Rural Reflections”, Stuart Haddon-Riddoch comments that traps were readily available in England and taken as essentials with settlers to Canada and North America. Records show that between 1751 and 1786, the Hudson Bay Company imported traps of different sizes from England. Presumably, (at least) a proportion of these traps were manufactured in the trap making centre of Wednesfield.

a magnet for trap makers

Developments in the Victorian era meant that people came to Wednesfield from other areas to learn the skills of trap making and/or to work in the trade. My great great grandfather, John Williams, came from Wolverhampton to Wednesfield to complete an apprenticeship in trap making under John Tottey. By 1851, John Williams was the one of the five largest trap makers in Wednesfield, but the only one of those five who was not born there.

By 1871, half of the trap masters mentioned in an article in the Birmingham Daily Post were born outside the village:

Joseph Bellamy

Edward, Luke & William Marshall

Joseph Tonks

Henry Lane

Joseph Tomlinson

Richard Ward

Thomas Beech (Pendeford)

William Ford (Weddington, Warwickshire)

Samuel Griffiths & Son (Tipton)

Nehemiah Phillips (Coventry)

James Roberts (Birmingham)

William Sidebotham (Bushbury)

John Williams (Wolverhampton).

growth factors moving into the 20th century

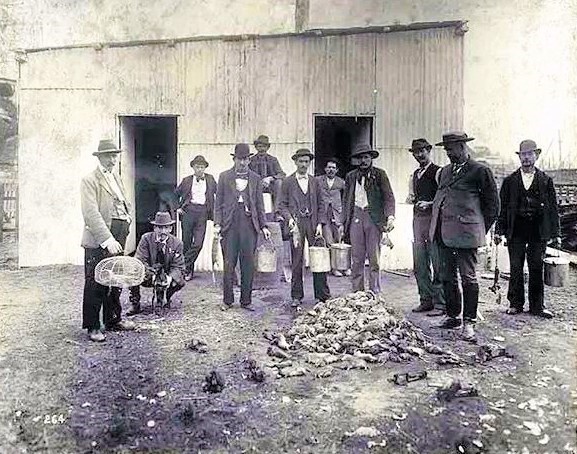

In 1898, both the Dundee Evening Telegraph and the Daily Gazette for Middlesborough reported that Wednesfield had a yearly output of 1,560,000 traps, exported to all parts of the world. In 1930, Benn’s Encyclopedia stated that Wednesfield produced 2,000,000 traps a year and had exported animal and vermin traps to all markets in the world. These numbers would indicate that trade actually rose rather than declined during this period.

What exactly contributed to this increase in trade volume?

Let’s look at 3 factors:

i) Rabbits are not native to either Australia or New Zealand but were introduced for food and hunting in the 19th century. Having no natural predators, rabbits spread like a plague across both countries, destroying crops and land leading to the decline of native animal and plant species.

In 1877, a government paper entitled “Methods for Diminishing the Rabbit Nuisance” was presented to the General Assembly in New Zealand. A section on instructions for trappers was contributed by Samuel Griffiths, the master trap maker of Wednesfield named above.

The Sydney Mail reported that rabbits caused losses that cost Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand three million pounds sterling in 1883. Traps were imported in large quantities from Wednesfield.

In 1894, the Birmingham Daily Post reported:

New Zealand Trade Prospects

… the rabbit pest still defies all the efforts yet put forth to exterminate the plague. Miles of wire netting and hundreds of grosses of rabbit traps are being imported into the colony, but without any tangible result … rabbit-traps are in enormous demand, and although Germany sends out large consignments the traps most in favour are of English make, Wednesfield and Willenhall being the chief producers – the prices at which these articles are imported ranging from 3s. 6d. to 4s. 6d. per dozen according to quality.

In 1898, the London Daily News commented:

It is true of many of our English villages that though comparatively unknown in themselves, their products and manufactures are used and appreciated in all parts of the world. Such a place is Wednesfield, near Wolverhampton, a densely populated, straggling village, urban and smoky enough on the Wolverhampton side, but on the other stretching away to the fringe of some very pretty green borderland. Its staple industry is steel trap making, the rabbit pest in Australia providing a good market for this article.

A report on import markets in the Sydney Daily Telegraph in 1916 quoted that rabbit traps were being imported from four companies, three of which were Wednesfield firms – Henry Lane, William & George Sidebotham and Samuel Griffiths and Sons. Haddon-Riddoch records that thousands of rabbit traps made by Sidebotham’s were packed into large metal tanks made by Davis’s of Cannock Road in Wolverhampton and that these large tanks were ultimately used as water containers in the Australian outback.

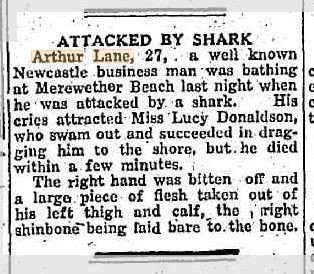

The Newcastle Morning Herald in Australia stated in 1920 that over 30,000 rabbit traps a year were being imported. It was in this year that Henry Lane Limited of Wednesfield established a secondary plant in Australia.

Arthur Edward Lane, grandson of the company’s founder, managed this works until his death in 1928:

ii) A second global event created a huge demand for rat traps, a long staple of Wednesfield’s trade. The outbreak of the Third Pandemic of bubonic plague emerged in China in 1855 and hit Hong Kong in 1894. The disease spread to India and then to many ports across the world, carried by infected rats. The Third Pandemic did not end until 1959 after causing 15 million deaths.

In 1900, the Birmingham Daily Post reported:

The demand for rat traps has become prodigious …

There is no exaggeration in the statements that its (epidemic plague) upon the trade of Sydney have been disastrous, with the exception of the sale of disinfectants and rat traps. For rats, it is admitted, disseminate the plague, and a smart writer in the ‘Australian Ironmonger’ advises all to ‘starve the rats and stop the plague’. The rat trap makers at Wednesfield and Willenhall have during the last few months been reaping a rich harvest of trade in consequence of rodents in the capital of New South Wales.

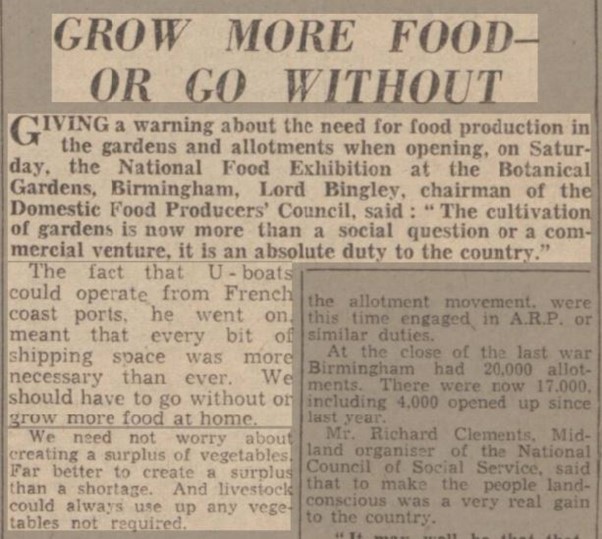

iii) During World War II, the Ministry of Agriculture launched the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign encouraging British citizens to grow their own food.

Wednesfield’s trap makers had a hand in this campaign. In 1943, the Birmingham Mail reported that Wednesfield, the trading centre of the trap industry that had exported thousands of traps to all parts of the world before the war, was now playing its part in the war effort as the domestic market for traps had grown by ‘leaps and bounds’. The Evening Despatch reiterated that Wednesfield was the centre of the British steel trap industry, stating that there was a huge demand for both rabbit and mole traps. Farmers bought rabbit traps in large numbers to keep the rabbit population in check and Sidebotham’s trap making firm commented that it was difficult to meet the demand for mole traps.

(2) A SOPHISTICATED BLACK COUNTRY INDUSTRY

Narrative:

Trap Making was just another metal bashing industry in the Black Country.

Wednesfield with its trap making industry had characteristics that distinguished it from other Black Country communities.

The Birmingham Daily Gazette made the following comments in 1868:

Wednesfield is the beau-ideal of an old Black Country town. It presents the quaint mixture of town and country, garden and workshop, toil and ease, which distinguished the other towns of the district half century ago. Walking down its one wide street lined with homesteads of charming irregularity, and relieved by foliage out-peeping from every eligible nook, one can well imagine what such places as Willenhall and Wednesbury were in the days when our fathers went thither ‘a-gipsying a long time ago’. In those old times Wednesfield compared not unfavourably with these great industrial haunts both in point of fame and population, but the toil and enterprise of half a century have lifted the latter far above their ancient rival as Birmingham soars above the Royal town of Wolverhampton …

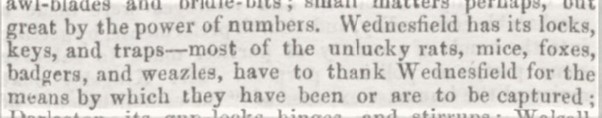

The location of trades is among the mysteries of the Black Country. Why Walsall should have decided in favour of leather, or Willenhall in favour of locks and keys, or Darlaston in favour of screw-bolts, is and must remain one of the industrial puzzles of the district. Wednesfield’s first love was the manufacture of traps and it has proved constant in its attachment.

good industrial relations

Trap making was a comparatively sophisticated and well organised trade. Relations between the masters and men seem to have been relatively cooperative and the trade did not operate with middlemen such as the foggers in the nail industry or the butty men in coal mining. A truck or tommy system, where workers were paid with credit at employers’ retail shops, never existed at Wednesfield as it did in other Black Country locations.

Wage demands or disagreements tended to be settled quickly and amicably and there are no records of long damaging strikes in which workers were starved into submission. The Birmingham Daily Post reported for instance that an agitation had commenced among the operatives for shorter hours and a modification of the wages scales on 8 November 1871. A conference between the masters and the workers was held at the Temperance Hall in Wednesfield on 23 November. Both sides aired their grievances and opinions and the masters made concessions. The Birmingham Daily Post stated the conference was one of the:

most gratifying conferences between masters and men that had ever been held in the Black Country.

By 6 December, the same newspaper was able to inform its readers that the trap makers had succeeded in securing an advance on their wages and were fully occupied.

product development and diversification

Trap making was complex and skilled, a step beyond mere ‘metal bashing’. Two retired engineers acting as volunteer guides at Sidebotham’s former trap works at the Black Country Living Museum told me a few years ago that they had tried to make their own traps and emulate what the past masters in Wednesfield produced. They failed.

Wednesfield trap makers consistently developed and improved their products. Once more, this is in strong contrast to the example of nail manufacturing in the Black Country where the product and means of manufacture did not evolve so that this failure to move forward became a contributory factor in the decline of the industry in the Black Country. Trap making took a very different path. An example is Henry Lane Limited.

The company held over 20 British patents as well as patents in Australia, New Zealand the USA, winning first prize medals at trade exhibitions in Belgium, Australia, the Netherlands and New Zealand. The company’s response to the demand for rabbit traps in Australia and New Zealand was to upgrade its plant and devise machinery to replace skilled labour, becoming ‘the most up to date of its kind in the world’. Haddon-Riddoch documents that Henry Lane Limited was manufacturing over 150 types of trap before World War II.

A vast number of different sizes and types of traps were produced by all manufacturers.

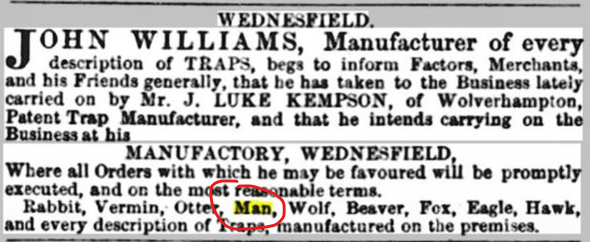

An advertisement taken out by John Williams in the Wolverhampton Chronicle in 1862 states he made rabbit, vermin, otter, man, wolf, beaver, fox, eagle and hawk traps.

James Roberts produced dog, otter, rabbit, fox, stoat, lion, beaver, kangaroo, tiger, hawk, owl, wolf, heron, musk, bird, cat, vermin, rat, American otter and tomtit traps.

Various advertisements from Henry Lane advertised traps for vermin, stoats, weasels, foxes, badgers, jackals, dogs, dingoes, beavers, otters, moles, poles, musk, herons, hawks, kingfishers, jays, magpies, wolves, lions, tigers, bears and so on.

Aris’s Birmingham Gazette in 1866 noted that:

Traps – rat, rabbit and vermin – are the leading productions of Wednesfield. Occasionally the makers are required to construct enormous tiger traps for the jungles of India and bear traps for mountain wilds of Russia, which enormous instruments they construct as readily in proportion to their size as the tiny snare which betrays the unwary field mouse or the unsuspecting sparrow.

In its “Rambles in Staffordshire” in 1867, the Birmingham Journal declared that:

Visions of the jungle rise up at the mention of the lion traps of Wednesfield,

cooperation and protection

The trap masters worked together to protect their trade and formed the Amalgamation of Steel Trap Manufacturers in 1898. The Dundee Evening Telegraph reported that 17 trap makers had formed the syndicate with a capital of £100,000 and that the aims of the Wednesfield trap makers were to control pricing for mutual benefit and to work against American and German competition.

The level and effects of this cooperation were fully demonstrated in 1908 when the Governor of Nigeria imposed a one shilling tariff on every trap imported into Nigeria. The Trap Manufacturers’ Association took action, lobbying the Colonial Office and enlisting the help of local Members of Parliament. Hansard records the following question and answer in parliament on 17 December:

Mr. T. F. Richards

(Member of Parliament for Wolverhampton West)

I beg to ask the Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies whether he is aware of the effect of the tax put upon traps exported from this country to Southern Nigeria upon the makers of these traps in the Wednesfield district of Wolverhampton and also upon the natives who augment their income by trapping, and who now claim that the trapping is checked for the benefit of sport and sportsmen; and whether his Department will advise the removal of this tax until at least the policy has been accepted by the Government.Colonel Seely

(Colonial Office)

As regards the effect of the increased duty upon the makers of the traps, and the policy of the Government in this matter, I can add nothing to the very full printed reply which I gave on the 8th of this month to my hon. friend the Member for Wolverhampton. No complaints have reached the Colonial Office from the natives, nor any suggestion that trapping is checked in the interests of sport, and I may observe that the proposal to increase the duty was carried unanimously in the Legislative Council with the support of the native members.

A meeting was held at the Colonial Office in March 1909 together with Colonel Seely, the Governor of Nigeria and George R Thorne, the Member of Parliament for Wolverhampton East. The Trapmakers’ Association was represented by James Roberts, William Sidebotham and Joseph Tonks. The Governor agreed to drop the tariff provided that traps were exported without teeth, the Wolverhampton Chronicle recording this outcome as a ‘Trapmakers’ Victory’.

(3) CRUEL & UNNECESSARY

Narrative:

Animal traps were cruel and unnecessary. Man traps were purchased and used in the slave trade. It is not politically correct to celebrate the trap making industry in Wednesfield.

instruments of torture?

Traps were not pleasant humane instruments, particularly when viewed from today’s perspective. Nevertheless, it is incorrect to conclude that traps were unnecessary. Most references to the Wednesfield trap making trade in 19th and 20th century newspapers refer to vermin traps or rabbit traps. The demand for rabbit traps to combat the rabbit plague in Australia and New Zealand and the need for rat traps in the Third Pandemic of bubonic plague demonstrate that traps were both an economic and social necessity.

Rat infestations were also a domestic problem in Britain’s growing urban areas and a selection of newspaper headlines confirms this –

- “a workhouse infested by rats” (1886)

- “monster rats in London docks” (1889)

- “an Edinburgh butcher´s shop infested by rats” (1886)

- “an infirmary infested by rats” (1890)

- “a plague of rats – Great Northern railway company’s warehouse” (1906)

- “rat infested London” (1905)

- “rat infested mortuary” (1907)

to quote a few.

Vermin traps were also exported, used in agriculture and on landed estates:

The Wednesfield trap makers are well employed, principally for the home trade. The demand for vermin traps for the estates of English noblemen has this year been unusually extensive.

Birmingham Daily Gazette, 1864.

In the rural districts the trap makers have slightly improved demand for vermin traps for country trade

Birmingham Daily Post, 1865.

At Wednesfield the trap makers are busy in the rabbit and vermin branches for the United States

Wolverhampton Chronicle, 1866.

At Wednesfield the country trade for rabbit traps is described as ‘better, and likely still further to improve’. Rats and vermin traps are in more buoyant demand, and prices are steadier.

Sheffield Independent 1868.

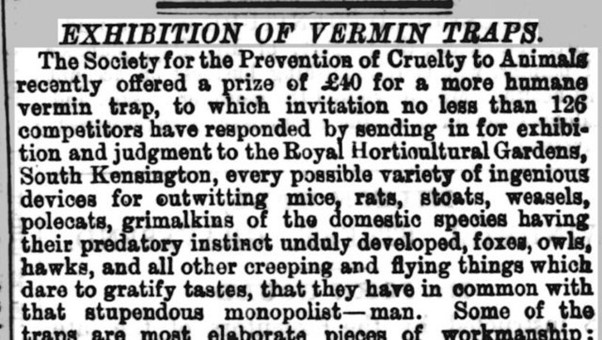

Concerns about animal cruelty and the need and demand to make traps more humane are not modern 21st century concerns. This prize was offered in 1865:

The trap makers themselves were not blind to these demands and wishes for more humane traps. In 1870, the Birmingham Daily Post reported that a leading Wednesfield manufacturer, Mr Bellamy, had introduced a rat trap that did not kill or injure which was regarded ‘with much favour’ among the sporting fraternity. The response to addressing Nigerian concerns on the humanitarian issues in 1908 was to agree to manufacture toothless traps and Wednesfield produced samples that were sent to the Colonial Office.

Again, it is worth quoting Stuart Haddon-Riddoch:

Due to most people being born and brought up in cities or large towns, it is true to say that the British population has lost contact with the countryside and its wildlife. … Urban people see animals differently from the country person and these differences have contributed to the flourishing of the ‘Animal Rights’ organisations in Britain. What these well-meaning people often fail to see is that with proper control of the various wild animals … both mankind and surprisingly the animals can benefit from each other.

the slave trade?

Discussions or talks about the trap industry in Wednesfield will generally bring up questions about man traps, a type of trap that has attracted a disproportionate amount of attention.

Man traps were manufactured in Wednesfield but were banned for use in Britain in 1827. They feature in trade directories for Wednesfield in the early 19th century and Wednesfield seems to have continued some production of these traps for export after 1827. For instance, this advert was placed by my great great grandfather in the Wolverhampton Chronicle in 1862:

However, I have scoured newspaper sources from different countries to find any reference to traps manufactured in Wednesfield being used in the slave trade. I mean any reference to traps. This has included examining countless references to traps including horse and traps, trapped legs in accidents, greyhound racing traps and so on.

Not one single mention has been found in the 19th and 20th centuries to indicate that Wednesfield traps were used in the slave trade or indeed in prisons or transportation. Man traps were rather used to protect property, frequently by gamekeepers on landed estates, against poachers and trespassers.

Furthermore, the export markets mentioned in trade reports throughout the years did not include countries that are automatically connected with the slave trade. An exception here is the United States of America which seem to have imported vermin, rabbit and otter traps rather than man traps.

In 1868, the Birmingham Daily Gazette appeared to refer to man traps as a discontinued trade:

Man traps have also been constructed here (Wednesfield), for the protection of gardens and orchards, which might prove tempting to the passer-by, but accustomed depredators have grown to place little faith in the frequent placard, ‘man traps set here’.

Stuart Haddon-Riddoch gives a detailed description of the manufacture and use of man traps in “Rural Reflections” and he does make a reference to the slave trade:

After May 1827, presumably for a short while mantraps would probably still be sold to plantation owners and used as deterrents to stop ‘their’ slaves from running away. In America, slavery was only declared illegal, after the Civil War, by Lincoln in 1865, so there may still have been a small export market to that country.

“Rural Reflections” is a valuable and trustworthy resource but this statement, qualified by “presumably”, probably” and “may”, is sketchy evidence. It would be erroneous to make strong conclusions on the basis of this statement. It could indeed be that man traps were used in slave plantations prior to the 19th century but there is a lack of documentary evidence.

In conclusion, possible connections with the slave trade cannot be definitively excluded but should not be the basis for burying the Wednesfield trap industry in a politically correct grave of unwanted Black Country history.

RESEARCH & ARTIFACTS

If you come across a trap maker in your family history, the first step is to consult “Rural Reflections” by Stuart Haddon-Riddoch. The Wednesfield trap makers all seem to be listed and Haddon-Riddoch’s research will give you a sense of how large or important your trap maker ancestor was. Indeed, I found out about my great great grandfather’s (John Williams) business for the first time when Wolverhampton Archives referred me to this work. This was the start of a long, detailed and fascinating voyage of discovery. The Wednesfield trap making families are often interconnected. The Marshalls occur in my family tree for instance as my great grandmother’s second marriage was to Charlie Gregory whose grandmother was Luke and Edward Marshall’s sister.

Two trap making business premises remain. The first is William Sidebotham’s works from 1912 that was on Graiseley Lane and rebuilt at the Black Country Living Museum in 1984. The contents of the workshop and office were also removed to the museum. Unfortunately, the trap works is not given a lot of attention by staff and visitors. For years, it had an audio guide that never worked and there is often no guide or volunteer present. The quality of the information given to visitors varies. Once, I listened to a guide informing a group of German visitors about the child labour used in the trap works, a sweeping generalisation for Black Country industry that is not true for trap making. On the other hand, I was lucky enough on another occasion to come across the two engineers mentioned above who had taken an active interest in trap making. The second premises are in situ at 43 Taylor Street in Wednesfield, the site of John Williams’ home and business. These were threatened with demolition but were converted into modern residences so that the historical feel of a trap making business has been retained.

The graves of many of the trap makers and masters are at Wednesfield new burial ground on Graiseley Lane, now closed to burials. It is fitting that the first burial at this ground was of a trap maker in 1855, that of Thomas Tomkys, brother to 4x great grandfather mentioned above.

Most Wednesfield workshops have disappeared but traps still exist at museums and antique and vintage traps are collected. I have a small number from John Williams & Son that were kindly given to me by a collector. Wolverhampton Art Gallery and Museum has several traps made by James Roberts and many examples of William Sidebotham traps are at the Black Country Living Museum. Recently, someone contacted me to say that he had dug up a John Williams trap in a field in Colchester!

The only man trap I have seen is displayed in the Prison & Police Museum at Ripon in Yorkshire.

It is surprisingly large and certainly not a pleasant device but the board at the museum confirms my research that man traps were used to deter and catch poachers. I couldn’t find a manufacturer’s stamp on this display but it was very probably made in Wednesfield.

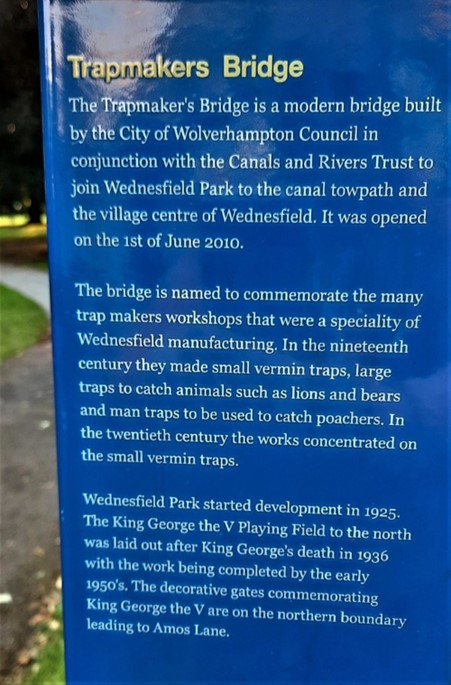

Wolverhampton City Council acknowledged the trap makers by constructing the Trapmakers’ Bridge that links the George V playing fields to the back of the High Street on the Wyrley and Essington Canal at Wednesfield in 2010.

Very thorough research as always.

It’s interesting to compare industrial relations in this industry with the mining industry. I wonder if the trap masters were closer to their workers having come from a similar background and area? The co-operation between the trap masters to compete with the industry of other countries is also remarkable.

There is a current debate about the use of poisons to kill rodents, increasingly unacceptable because the poisons can be very unpleasant and leak into the environment. But we don’t now try to trap Grimalkins (cats – I had to check)!

Have had a couple of rat traps for40 years found buried in old tip . Just cleaned them up-a bit to discover H Lane , maker , further letters and possible date 1859. Any use to anyone? Museum?

Your traps are from Henry Lane. I hope your post finds a museum or family member that is interested. Thanks for posting!